Women and Repression in Communist Czechoslovakia

Today’s blog post, written for International Women’s Day 2016, relates to my current research into women’s experiences of repression in communist Eastern Europe, with a particular focus on Czechoslovakia 1948-1968, during the period of Stalinist terror and its immediate aftermath.

The vast majority of the 90,000 – 100,000 Czechoslovak citizens who were prosecuted and interned for political crimes between 1948-1954 were men; only between 5,000 – 9,000 (5-10%) were women. These women were held in numerous different prisons and forced labour camps across Czechoslovakia, where they frequently experienced poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene and medical care and enforced labour, while enduring physical and psychological violence, abuse and humiliation at the hands of the penal authorities. Beyond this, however, hundreds of thousands of other Czechoslovakian women also became ‘collateral’ victims of state-sanctioned repression during these years. The Czechoslovakian Communist Party actively pursued a policy of ‘punishment through kinship ties’, so while family members of those incarcerated for political crimes were not necessarily arrested themselves, they were considered ‘guilty by association’. As men comprised the majority of political prisoners, it was usually the women who were left trying to hold their families together and survive in the face of sustained political and socio-economic discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

The growth in published memoirs and oral history projects such as Paměť Národa and Političtívězni.cz in post-communist Czech Republic and Slovakia have encouraged more victims of repression to record their stories. However, women’s experiences of political repression in communist Czechoslovakia remain under-researched and under-represented in the historiography. It is often suggested that women are generally more reluctant to share personal accounts of traumatic experiences, in comparison with their male counterparts. For example Historian Tomáš Bursík’s study of Czechoslovakian women prisoners Ztratili jsme mnoho casu … Ale ne sebe! notes that in many cases ‘Women do not like to return to their suffering, that misfortune they affected, the humiliation that followed. They do not want to talk about it’. In her own account of imprisonment in communist Czechoslovakia, Krásná němá paní, Božena Kuklová-Jíšová also explained that:

‘We women are very often criticized for not writing about ourselves, about our fate. Perhaps it is because there were some moments which were very humiliating for us; or because in comparison to the many different brave acts of men, our acts seem so narrow-minded. But the main reason is that we have difficulties presenting ourselves to the world’.

This reticence extends to many women who experienced collateral or secondary repression, such as Jo Langer, who despite being subjected to sustained political harassment and socio-economic discrimination including loss of employment and forced relocation when her husband Oscar was arrested and interned 1951-1960, described how, upon receiving the first full account of her husband’s traumatic experiences in the camps after his release, she felt ‘shattered and deeply ashamed of having thought myself a victim of suffering’ (You can read more about Jo Langer’s autobiography Convictions: My Life with a Good Communist in my previous blog post HERE)

However, the inclusion of women’s narratives make an important contribution to the historiography, broadening and deepening our understanding of terror and repression in communist Eastern Europe. A number of women who endured political repression have shared their stories, which not only document their suffering at the hands of the Communist Party but are also testimony to their strength, resistance and will to survive. Through their narratives, these women are able to present themselves simultaneously as both victims and survivors of communist repression.

Today then, it seems fitting to mark International Women’s Day 2016 by briefly highlighting two examples to pay tribute to the many strong, spirited and inspiring women who feature in my own research.

Dagmar Šimková

“The screeching seagulls are flying around me. I am so free, I can walk barefoot. And the waves wash away traces of my steps long before a print could be left”.

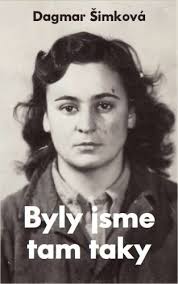

Dagmar Simkova’s arrest, official photograph (1952). Source: http://zpravy.idnes.cz/autorka-svedectvi-o-zenskych-veznicich-krasna-a-inteligentni-dagmar-simkova-by-se-dozila-80-let-i1u-/zpr_archiv.aspx?c=A090522_114346_kavarna_bos

Dagmar Šimková’s autobiographical account of her experiences in prison Byly jsme tam taky [We were there too] is arguably one of the strongest testimonies of communist-era imprisonment to emerge from the former east bloc. Šimková’s family became targets after the communist coup of 1948 due to their ‘bourgeois origins’ (her father had been a banker). Their villa was confiscated by the Communists, while Dagmar and her sister Marta were denied access to university. While Marta fled Czechoslovakia in 1950, Dagmar became involved in resistance activities, printing and distributing anti-communist leaflets and posters mocking the new Czechoslovakian leader, Klement Gottwald. In October 1952, following a failed attempt to help two friends avoid military service by escaping to the West, she was arrested, aged 23, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Between 1952 – 1966 Šimková passed through various prisons and labour camps in Czechoslovakia: in Prague, Pisek, Ceske Budejovice and Opava. In 1955 she even briefly escaped from Želiezovce, a notoriously harsh agricultural labour camp in Slovakia. Sadly, her freedom was shortlived: she was found sleeping in a haystack at a nearby farm two days later, recaptured and returned to Želiezovce, where an additional three years was added to her existing prison term as a punishment.

Dagmar Simkova’s book Byly Jsme Tam Taky [“We Were There Too”]

From 1953, Šimková was held in Pardubice Prison near Prague, in the women’s department ‘Hrad’ (Castle), which was specially created to house 64 women who were perceived as being the ‘most dangerous’ political prisoners, and segregate them from the main prison population. Here, Šimková participated in several organised hunger strikes to demand better conditions for women prisoners. She was also an active participant in the ‘prison university’ founded by former university professor Růžena Vacková, who gave secret lectures on fine art, literature and languages to her fellow prisoners. Šimková later described how ‘We devoured every word. We tried to remember, and understand, like the best students at universities’. Some of the women even managed to compile some lecture notes into a small book which was secretly hidden, before being smuggled out of Pardubice in 1965. This book is currently held in the Charles University archives.

After a total of fourteen years incarceration, Dagmar Šimková was finally released in April 1966, aged 37. Two years later, during the liberalisation of the Prague Spring in 1968 she was instrumental in establishing K 231, the first organisation to represent former political prisoners in Czechoslovakia. Following the Soviet invasion to halt the Czechoslovak reforms, Šimková emigrated to start a new life in Austrialia, where she completed two University degrees, worked as an artist, prison therapist and even trained as a stuntwoman! She also worked with Amnesty International , continuing to campaign for better prison conditions until her death in 1995.

Heda Margolius Kovály

Heda Margolius Kovaly. Source: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/dec/13/heda-margolius-kovaly

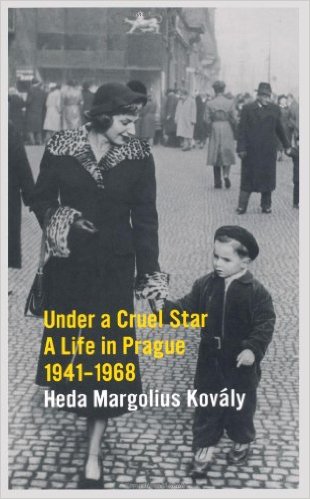

Heda Margolius Kovály’s memoir, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 remains one of the most damning accounts of the violence and repression that characterised mid-twentieth century central and eastern Europe. Heda’s incredible life story spans the Nazi concentration camps, the devastation of WWII, the communist coup and the post-war Stalinist terror in Czechsolovakia. Having survived Auschwitz, Heda escaped during a death march to Bergen-Belsen and managed to make her way home to Prague. After the war, she was reunited with her husband Rudolf Margolius, who was also a concentration camp survivor, and a committed communist. Following the Communist coup of February 1948, Rudolf served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, only to quickly fall victim to the Stalinist purges. Rudolf was arrested on 10 January 1952, brutally interrogated and forced to falsely confess to a range of ‘crimes’ including sabotage, espionage and treason. He was subsequently convicted as a member of the alleged ‘anti-state conspiracy’ group led by former General Secretary, Rudolf Slansky, in Czechoslovakia’s most infamous show trial. In December 1952, Rudolf was executed, along with 10 of his co-defendents.

Following Rudolf’s arrest, Heda described how ‘Suddenly, the world tilted and I felt myself falling … into a bottomless space’ . She was left to raise their young son, Ivan, while fighting to survive in the face of sustained state-sanctioned repression. She was swiftly fired from her job at a publishing house, and was forced to work extremely long hours for pitifully little pay, while living on ‘bread and milk’ in order to make enough to cover their basic needs. Her savings and most of her possessions were confiscated, and she and Ivan were forced to leave their home and move to a single room in a dirty and dilapidated apartment block on the outskirts of Prague, where it was so cold that ice formed inside during the winter months, and cockroaches ‘almost as large as mice’ crawled up the walls. Abandoned by most of her former friends, Heda describes how she became a social pariah who was treated ‘like a leper’. At best, former friends and acquaintances would ignore her when they passed in the street, while others would ‘stop and stare with venom’ sometimes even spitting at her as she walked by.

The strain of living under these conditions caused Heda to become critically ill, but she was initially denied medical treatment. When she was finally admitted to hospital she had a temperature of 104 and a long list of ailments, leading the doctor who treated her to compare her to a newly released concentration camp survivor. It was while she was recovering in hospital that she heard Rudolf’s trial testimony broadcast on the radio, and she listened to her husband monotonously admit to ‘lie after lie’ as he recited the script he had been forced to learn. Forcibly discharged from hospital before she was fully recovered, Heda was so weak that she had to crawl ‘inch by inch’ from the front door of her apartment block to her bedroom, where she spent several weeks following Rudolf’s execution ‘motionless, without a thought, without pain, in total emptiness … lying in my bed as if it were a coffin’.

‘Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968’ is Heda Margolius Kovaly’s account of surviving Nazi and Communist persecution.

Nevertheless, Heda regained her strength. Her son Ivan later described how, even in the face of sustained persecution ‘Heda survived through her determination and managed to look after us both’. She continued to maintain Rudolf’s innocence and fought to clear his name, writing endless letters and attempting to arrange meetings with various communist officials, most of whom refused to see her. Following Rudolf’s execution, she dared to publicly mourn him by dressing completely in black, in a deliberate challenge to the Communist Party. After she remarried in 1955, she continued to campaign for Rudolf’s full rehabilitation. In April 1963, she was finally summoned to the Central Committee where Rudolf’s innocence was privately confirmed, and Heda was asked to write a ‘summary of losses’ suffered as a result of his arrest and conviction, so that she could apply for compensation. In Under a Cruel Star, she described how:

‘I sat down at my typewriter and typed up a list:

– Loss of Father

– Loss of Husband

– Loss of Honour

– Loss of Health

– Loss of Employment and Opportunity to Complete Education

– Loss of Faith in the Party and JusticeOnly at the end did I write:

– Loss of Property’.

Upon presentation of this list, the Communist officials responded in confusion:

‘”But you must understand that no one can make these losses up to you?”. “Exactly” I said “That’s why I wrote them up for you, So that you know that whatever you do you can never undo what you have done … you murdered my husband. You threw me out of every job I had. You had me thrown out of a hospital! You threw us out of our apartment and into a hovel where only by some miracle we did not die. You ruined my son’s childhood! And now you think you can compensate for that with a few crowns? Buy me off? Keep me quiet?”.’

Following the failed Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Heda left Czechoslovakia and settled in the USA with her second husband, Pavel Kovály. There, she continued to forge a successful career as a translator in addition to working as a librarian in the international law library at Harvard University. Heda Margolius Kovály died in 2010, aged 91. In addition to her personal memoir Under A Cruel Star, an English-language translation of Heda’s novel Nevina [Innocence] was recently published in 2015 – which I can also highly recommend!

The Evolution of the Polish Solidarity Movement

THE EVOLUTION OF THE POLISH SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT – BY KIERAN INGLETON.

The Solidarity movement in Poland is arguably one of the most unique and inspiring movements in modern European history. Between 1980-1989, Solidarity led what has often been described as a “10 year revolution”, which ultimately resulted in the collapse of communism in Poland, a key turning point which triggered wider reform and revolution across the Eastern bloc. During this turbulent decade, Solidarity evolved from a legal trade union into an underground social network and protest movement, ultimately emerging as a revolutionary force, capable of toppling and replacing the communist system in Poland. (Bloom, 2013, pp374-375). Mark Kramer has argued that while Solidarity may have started out as a free trade union, it “quickly became far more: a social movement, a symbol of hope and an embodiment of the struggle against communism and Soviet domination” (Kramer, 2011).

THE BIRTH OF SOLIDARITY

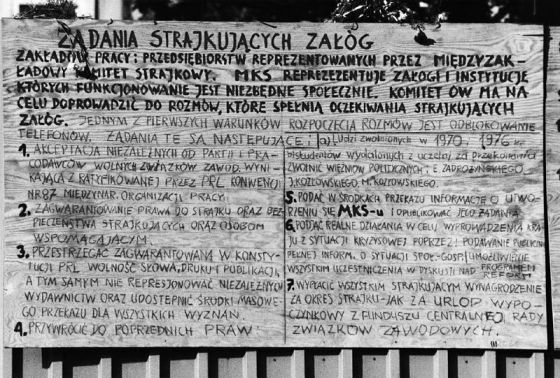

The Solidarity movement emerged out of a much longer history of worker discontent, strikes and protest that had characterised tensions between the state and society in communist Poland since the end of WWII. Touraine has argued that “Solidarity first emerged because it was a response to Poland’s decline economically and socially. Nowhere else in Communist Central Europe was the failure of the governments industrial and agricultural policies so obvious” (Touraine, 1983, p32). From the mid-1970s, the Polish economy had slipped more deeply into an irreversible economic decline, as production levels plummeted, real wages stagnated, shortages increased and foreign debt mounted, reaching $18 billion by 1980 (Paczkowski & Byrne, 2007. p. xxix). In 1980, a Polish Communist Party (PUWP) announcement about increasing food prices triggered a fresh wave of strikes across Poland. At the Lenin Shipyards in Gdansk, workers were further incited by the dismissal of crane driver and trade union activist Anna Walentynowicz, and in response, around 17,000 workers occupied the shipyard on 14 August. On 17 August, the Gdansk strike committee, led by Lech Walesa, drew up a list of ‘21 demands’, which were famously displayed on the gates of the shipyard. While several of the demands were pragmatic (such as improved economic conditions and the right of workers to strike) others were more politicised (including demands for reduced censorship and freedom for political prisoners). Notably, at the top of the list, the strikers demanded the establishment of free trade unions, independent from Communist Party control, to better represent workers’ rights.

The 21 Demands drawn up by the strike committee, displayed on the gates of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980. Source: http://www.solidarity.gov.pl/?document=61

When the Polish leader, Edward Gierek, turned to Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev for advice, Brezhnev encouraged him to seek a ‘political solution’ rather than forcibly subduing the strikes (having recently sent Soviet troops into Afghanistan, Brezhnev was keen to avoid the possibility of Gierek requesting ‘fraternal support’ from the Soviet military). As a result, the Polish leadership opened negotiations with the striking workers, and on 21 August a Governmental Commission arrived in Gdansk to begin talks, which resulted in the ‘Gdansk Agreement’ of 31 August 1980.

The Gdansk Agreement included authorisation for independent trade union representation of workers’ interests, and on 17 September 1980 the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union Solidarity (NSZZ – Solidarnosc) was officially formed. For the first time since the Communists had come to power the Polish people could join a trade union that was wholly independent from state control. However, Solidarity’s remit was clearly proscribed. The PUWP always intended their role to be limited to non-political representation, as the Gdansk Agreement stated that “these new unions are intended to defend the social and material interest of the workers and not to play the role of a political party”.

THE RISE (AND FALL) OF SOLIDARITY

As Jeffrey Bloom comments ‘‘The strikes of 1980 were the beginning of a social revolution. The nation emerged transformed, they were all aware of what was achieved, strike victory and solidarity helped create a sense of hope and self-confidence for future conflicts” (Bloom, 2013, p115). From its formation in September 1980, Solidarity grew rapidly, peaking with almost 10 million members by June 1981 (a figure which is estimated to have comprised around 70% of all workers in the state economy in Poland and around a third of the total population). Biezenski argues that in the twelve months following their formation, “Solidarity’s dramatic increase in activism was a logical response to a deepening economic crisis within Poland” (Biezenski, 1996, p262). The continued failure of the Communist Party to adequately address deteriorating conditions meant that “the social and material interests of the workers” that Solidarity had been founded to represent remained under threat, and as the months passed, it became increasingly clear that significant improvements to socio-economic conditions in Poland would not be possible without some kind of accompanying political restructuring. Emboldened by their rising support, Solidarity adopted an increasingly politicised stance and began agitating for a general strike. As Barker has argued: “Solidarity changed its members. The very act of participating in a founding meeting, often in defiance of local bosses, involved a breach with old habits of deference and submission. New bonds of solidarity and a new sense of strength were forged … [which] opened the door to a swelling flood of popular demands” (Barker, 2005).

This shift was clearly reflected by October 1981, when Solidarity published their official programme, which encompassed a combination of socio-economic and political aims, couched in increasingly revolutionary rhetoric. The programme attacked the failures and shortcomings of the Communist Party, referred to Solidarity as “a movement for the moral rebirth of the people” and stated that “”History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom … what we had in mind was not only bread, butter and sausage but also justice, democracy and truth”.

“Solidarity unites many social trends and associated people, adhering to various ideologies, with various political and religious convictions, irrespective of their nationality. We have united in protest against injustice, the abuse of power and against the monopolised right to determine and to express the aspirations of the entire nation. The formation of Solidarity, a mass social movement, has radically changed the situation in the country”.

– Solidarity’s Programme, 16th October 1981

As Pittaway points out, ‘The PUWP was thrown into disarray by the advance of Solidarity and its hold over public opinion’ (Pittaway, 2004, p175). Solidarity challenged the status quo, so that the normal mechanisms of communist control over the mass of the population began to break down (Barker, 2005). The Communists initially responded by launching a negative propaganda campaign, designed to damage Solidarity and discredit their leadership, including Walesa. The growing popularity and influence enjoyed by Solidarity also elicited concern from Moscow. On 18 October 1981, General Wojcech Jaruzelski was appointed as new leader of the PUWP. A known hardliner, Jaruzelski was given a clear mandate to suppress Solidarity. Until his death in 2014, Jaruzelski always maintained that he feared Soviet invasion if he had not moved swiftly to contain Solidarity, although the likelyhood of Soviet military intervention in Poland has been disputed. On 13th December 1981, Jaruzelski declared Martial Law and as tanks rolled onto the streets he addressed the people of Poland in a live TV broadcast:

“Our Country stands on the edge of an abyss … Distressing lines of division run through every workplace and through many homes. The atmosphere of interminable conflict, controversy and hatred is sowing mental devastation and mutilating the tradition of tolerance. Strikes, strike alerts and protest actions have become the rule … A national catastrophe is no longer hours away but only hours. In this situation inactivity would be a crime. We have to say: That is enough … The road to confrontation which has been openly forecast by Solidarity leaders, must be avoided and obstructed”.

– From Jaruzelski’s Declaration of Martial Law, 13 December 1981.

General Jaruzelski’s declaration of martial law in Poland, 13 December 1981. Source: http://www.rferl.org/content/Interview_Polands_Jaruzelski_Again_Denies_Seeking_Soviet_Intervention_Against_Solidarity/1902431.html

DEATH – AND REBIRTH

Following Jaruzelski’s declaration of Martial Law, and the creation of a ruling ‘Military Council of National Salvation’ (Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, or WRON), Solidarity was outlawed, its leaders arrested and its supporters repressed. An estimated 5000 Solidarity members were arrested; over 1700 leading figures were imprisoned (including Walesa) and 800,000 others lost their jobs. (Bloom, 2013, p297). Martial Law remained in force in Poland until July 1983.

However, although Solidarity were embattled, the movement survived. During the 1980s, Solidarity networks continued to function underground, focusing their efforts on illegally printing and distributing anti-communist literature, including books, journals, newspapers, leaflets, and posters. On April 12, 1982, ‘Radio Solidarity’ even began broadcasting. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persevered as an exclusively underground organization, promoting civil resistance, continuing their fight for workers’ rights and pushing for social and political change. Former Solidarity member Eva Kulik described how: “”We needed to break the monopoly of the Communist propaganda. And what people really needed was information”. As Feffer points out, the Solidarity trade union actually spent more of its existence in the shadows than as an official movement (Feffer, 2015). However, these underground years were formative in explaining the evolution of the movement. As Touraine has argued, after Jaruzelski forced the movement underground, Solidarity ‘now sought to liberate society – under the cover of a new rhetoric replacing the tired trade union vocabulary with that of a revolutionary movement” (Touraine, 1983, p183).

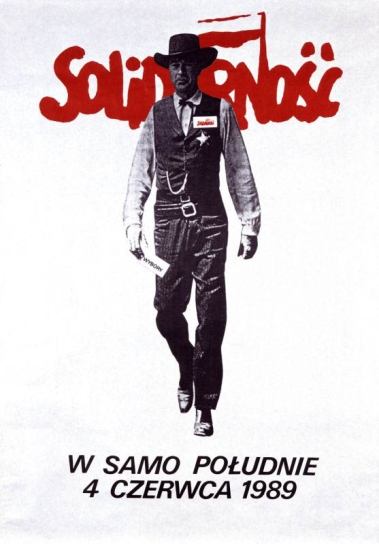

“High Noon” – famous Solidarity campaign poster, used during the Polish elections of June 1989. Source: https://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/699

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev’s appointment as Soviet leader finally bought more of a reformist agenda to the table in Eastern Europe, and by 1988, the Communists were ready to negotiate with Solidarity. Chenoweth believes that by that point the PUWP had little choice: continued economic deterioration in Poland (where rationing had been in place for most of the 1980s) meant that reforms were urgently needed and “the reality by 1988 was that Solidarity was too big and too broad to repress” (Chenoweth, 2014, pp61-62). While they had been driven underground in Poland, Solidarity enjoyed considerable support internationally, with Lech Walesa even being awarded the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 1983. During the famous ‘Round Table talks’ in the spring of 1989, the PUWP agreed to reinstate Solidarity’s original remit as an independent trade union. When Solidarity was re-legalized on 17 April 1989, its membership quickly increased to 1.5 million. However, by now many members of the Solidarity leadership had their eyes firmly on the main political prize. In June 1989, in the first semi-free elections in Poland since 1945, Solidarity represented the main opposition to the PUWP: campaigning as a legal political party, fielding Solidarity candidates against established Party members and sweeping to victory, winning all 161 contested seats in the Sejm [parliament], and 99/100 seats in the Polish Senate. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and in December 1990, Lech Wałęsa was elected President. Solidarity had come a long way from their roots in 1980, and now faced a new challenge: dismantling communism and overseeing Poland’s transformation into a modern, democratic European state.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

KIERAN INGLETON recently completed his BA (Hons) at Leeds Beckett University, graduating with Upper-Second Class honours in July 2015. During the final year of his degree Kieran specialised in the study of communist Eastern Europe, researching the evolution of Solidarity for one of his assessed essays. Kieran is particularly interested in the interaction between politics and society in totalitarian regimes, and his history dissertation explored the application of Totalitarian theory to Stalinism between 1928 and 1939. Kieran now plans to take a gap year, before studying for an MA in Social History.

SOURCES

Colin Barker,(2005) “The Rise of Solidarnosc”, International Socialism, 17 October 2005, http://isj.org.uk/the-rise-of-solidarnosc/

Robert Biezenski (1996), “The Struggle for Solidarity 1980-1981: Two Waves in Conflict”, Europe Asia Studies, 48/2

Jack Bloom (2013), Seeing Through the Eyes of the Polish Revolution: Solidarity and the Struggle against Communism in Poland. Haymarket Books.

Eric Chenoweth (2014) “Dancing with Dictators – General Jaruzelski’s Revisionists”, World Affairs, 10/3, http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/dancing-dictators-general-jaruzelski%E2%80%99s-revisionists

John Feffer (2015) “Solidarity Underground”, The World Post (2015) http://www.johnfeffer.com/solidarity-underground/

Mark Kramer (2011) “The Rise and Fall of Solidarity”, The New York Times, Op Ed http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/13/opinion/the-rise-and-fall-of-solidarity.html?_r=0

Andrzej Paczkowski and Malcolm Byrne. Eds. (2007) From Solidarity to Martial Law: The Polish Crisis of 1980-1981 : A Documentary History. Central European University Press, Budapest.

Mark Pittaway (2004) Eastern Europe 1939-2000. Cambridge University Press.

A Touraine (1983) Solidarity: Poland 1980-1981. Cambridge University Press.

The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia

THE RISE OF COMMUNISM IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA – BY SAM SKELDING

On 25th February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, led by Klement Gottwald, officially gained full power over the country. The communist rise to power was dubbed ‘Victorious February’ during the Communist era, and was celebrated each year, although since 1989 it has been more popularly referred to in slightly less positive terms, as ‘the February Coup’. It had taken just three short years for the communists to gain full control of Czechoslovakia following the end of World War II, but, by the standards of other East European countries, they were fairly late in establishing power. Just how did the communists managed to rise to the top in a country that had previously been heralded by many as a beacon of democracy and perceived as one of the most ‘Western oriented’ countries within central and eastern Europe? This article will explore some of the different factors that combined to create a climate favourable to the Communist Party’s ascension to power in Czechoslovakia after World War II.

WWII AND AFTER

Eastern Europe bore some of the worst experiences of World War II. It was here in the ‘bloodlands’ of Europe that the scars the war left behind were felt most keenly, and Czechoslovakia was no exception. Bradley Abrams has argued that WWII served ‘as both a catalyst of, and a lever for communism [in Czechoslovakia] … creating the intellectual and cultural preconditions for the Communist Party’s rise to total power’ after 1945 (Abrams 2004, p.105).

Although Czechoslovakia recovered most of its pre-WWII territory after 1945, in other ways things looked very different. Firstly, the ethnic and social makeup of Czechoslovakia changed significantly as a result of World War II. During the years of Nazi dominance, German ‘colonists’ began to move into the country whilst many Czechs and Slovaks were deported to forced labour camps or murdered. By 1945, 3.7 percent of the pre-war Czech population had died, including more than a quarter of a million Czechoslovakian Jews, who perished in the concentration camps (Applebaum, 2012, p.10). At the end of the war there was further significant population movement as President Benes authorised the organised expulsion of most of the 3 million ethnic Germans and Hungarians who were resident in Czechoslovakia, whilst thousands of other survivors gradually returned from labour and concentration camps. The decimation of various minority groups (including Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Jews and Roma) meant that following the end of the war, Czechs and Slovaks comprised 90% of the country’s population. This led to heightened nationalism which was subsequently manipulated by the Communist Party, ‘since they could take credit for providing opportunities for mobility and for satisfying nationalist aspirations.’ (Gross, 1989, p.203).

Economically, Czechoslovakia was also transformed by the war. During the years of Nazi occupation and dominance, many businesses were nationalized as the economy was reoriented towards the German war effort, turning Czechoslovakia into more of a ‘closed market’. When the war ended, Czechoslovakia retained a semi-nationalised domestic economy with few remaining international trade links, circumstances which made it easier for the Soviet Union to dominate Czechoslovakia’s post-war economic recovery, which ultimately, laid the groundwork for the post-war shift to Soviet style ‘central planning’. This is illustrated by the fact that, at the end of the War, returning Czechoslovakian President Eduard Benes asked Klement Gottwald, leader of the Communists, to work with the Social Democrats to prepare a decree to nationalise the remaining Czechoslovakian industry (a policy later evidenced in the April 1945 Košice Programme), which met little political opposition.

Czechoslovakia’s international relations also underwent a significant shift after 1945. The perceived failure of their previous political reliance on the West was confirmed after Czechoslovakia became the most famous victim of appeasement with the 1938 Munich agreement (which famously ceded part, and eventually all, of Bohemia to Germany), creating strong feelings of bitterness and insecurity.

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

—Neville Chamberlain, 27 September 1938.

British Prime Minister Neville Chaimberlain’s declaration that the Munich agreement, ceding control over Czechoslovakian territory to Hitler, would secure ‘peace in our time’. Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/nevill3.jpg

Cashman has subsequently argued that, in many ways, ‘the events of 1938 paved the way for the imposition of communism in Czechoslovakia.’ (Cashman, 2008, p.1647). This shift was later compounded when it was the Soviet Red Army who arrived to liberate most of Czechoslovakia from German control in 1945. The fact that it was the Soviets who, as Winston Churchill famously acknowledged, had ‘torn the guts out of Hitler’s war machine’ and secured Czechoslovakia’s freedom, increased Communist prestige in Czechoslovakia. The power and brutality many Czechoslovaks experienced at the hands of the Red Army during and after their liberation (in Czechoslovakia, as elsewhere in ‘liberated’ Eastern Europe, numerous cases of theft, violence and rape committed by Soviet soldiers were recorded) created an aura of fear and admiration around the USSR, as Applebaum remarked ‘The Red Army was brutal, it was powerful and it could not be stopped’ (Applebaum, 2012, p.32).

Finally, there was also widespread popular enthusiasm for social change in Czechoslovakia, which broadly supported a general political shift to the left and towards a more radical, socialist agenda at the end of World War II. Jo Langer described the change in public feeling after 1945, as ‘now the task was to erase the interruption and effects of the war and to help this country ahead on the old road to an even better future’ (Langer, 2011, p.27) while Marian Slingova suggested that ‘socialism in one form or another was the goal for many in those days. In Czechoslovakia, a revolution was in progress.’ (Slingova, 1968, p.40). Heda Margolius Kovaly explained how many who had lived through World War II ‘came to believe that Communism was the very opposite of Nazism, a movement that would restore all the values that Nazism had destroyed, most of all the dignity of man and the solidarity of all human beings’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.64). This all translated into increased levels of support for the Communist Party, who won 114 out of 300 contested seats, and 38 % of the popular vote in the May 1946 election, which, coupled with the support of their socialist allies, gave them a slim political majority of 51%. Robert Gellately has acknowledged that while non-communists were ‘shocked’ by this result, they ‘admitted that the [Czechoslovakian] elections were relatively free and not stolen, as they were elsewhere in Eastern Europe’ (Gellately, 2013, p.233).

THE COMMUNIST PATHWAY TO POWER

Following World War II, a National Government was formed in Czechoslovakia, comprised of 25 ministers, 9 of whom were Communist Party members. From the outset, the Communists were in an influential position, controlling some of the most important government ministries, with a political mandate to launch a sweeping programme of post-war, reform, with explicitly socialist and nationalist aims. Several key post-war politicians, including President Eduard Benes and Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, initially hoped they could work with the communists, while holding out hope that the Western powers would not simply stand by whilst Czechoslovakia fell to Soviet control, despite their bitter experience in 1938 (Lukes, 1997, p.255).

While many Czechoslovakians broadly supported the communist agenda, they hoped for the freedom to develop their own, independent, ‘national road to socialism’. However, between 1946-1948, the Czechoslovakian communists came under increasing Soviet pressure, both to secure sole power, and to conform to Stalinist-style socialism. In July 1947, Stalin’s show of displeasure with the Czechoslovak government’s initial willingness to accept U.S. Marshall Aid forced an immediate reversal of their decision, firmly illustrating the nature of the relationship between the two states. Czechoslovakian Foreign Minister (and non-communist) Jan Masaryk summed up his feelings, about the enforced refusal of Marshall Aid, when he declared that : “I went to Moscow as the Foreign Minister of an independent sovereign state; I returned as a lacky of the Soviet Government.”’ (Lukes, 1997, p.251). Stalin also used the founding conference of the Cominform in September 1947 to publicly criticise the French, Italian and Czechoslovakian Communist Parties for ‘allowing their opportunity to seize power to pass them by’, while the subsequent expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform in June 1948 sent a clear signal to the Czechoslovak communist leadership that the “national roads” policy was no longer supported by the Soviets.

Portraits of Klement Gottwald and Joseph Stalin at a 1947 meeting of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Gottwald_%26_Stalin.jpg

The mechanisms and intrigues surrounding the communist seizure of power in Czechoslovakia have been well documented. During 1947 – 1948 the Communist Party positioned themselves tactically, and one CIA intelligence report recognized that, ‘Having won the key cabinet positions in the May 1946 elections … the Communists have since steadily extended their control of the positions necessary for seizure of the government.’ (CIA, 1948).

By 1948, it appeared that the tide was starting to turn against the Communists, as their coalition partners became increasingly critical of their political tactics. In January 1948, controversy erupted after the communist controlled Minister of the Interior sacked a number of police officials who were not Communist Party members, leading their coalition partners to call for a full cabinet investigation Following this, on 10th February 1948, the socialist minister for the Civil Service won government support for a pay deal that had been strongly opposed by both the communists and the trade unions. However, Klement Gottwald successfully delayed the cabinet from returning to this issue until finally, on 20th February 1948, government ministers from the National Socialists, People’s Party and Slovak Democrats all resigned, in the hope of forcing new elections to reduce the communist’s influence in government. However, the Social Democratic ministers chose to side with the communists and refused to resign, which meant that together the two parties retained over half of the seats in parliament. Gottwald’s position was strengthened by the outbreak of large pro-communist demonstrations in Prague – largely orchestrated by the communists, but with some degree of popular support – so that rather than calling new elections, on 25th February President Benes agreed to the formation of a new government, dominated by the communists and their socialist allies.

As Klement Gottwald triumphantly addressed the crowds, Heda Margolius Kovaly recalled one elderly man’s reaction ‘the old gentleman was standing at the window, looking down at the crowded street. He did not even turn around to greet me. He said, very quietly, “This is a day to remember. Today, our democracy is dying” … Out in the street, the voice of Klement Gottwald began thundering from the loudspeakers.’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.74).

Pro-Communist demonstrations in Prague, February 1948. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Agitace-1947.jpg

Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader Klement Gottwald, addressing the crowds in Wenceslas Square, Prague, on 25 February 1948. Source: https://www.private-prague-guide.com/wp-content/klement_gottwald.jpg

Within weeks the socialists had agreed to formally merge with the communists and the subsequent elections in May 1948 (which were considerably less free than those of 1946!) resulted in the Communist Party gaining over 75 percent of the seats) and on 9 May 1948 a new constitution defined Czechoslovakia as a ‘People’s Republic’ (Swain & Swain, 1993, p64). A one party state had been created in Czechoslovakia, which was rapidly brought under firm Soviet control. From 1948 the Communists were forced to abandon any remaining efforts to retain ‘national’ socialism in Czechoslovakia, in favour of ensuring their country firmly fitted the Stalinist mould.

You can hear more about the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia in this video from the US National Archives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAM SKELDING recently completed his BA (Hons) in History at Leeds Beckett University and will graduate in July 2015. During his final year of study, Sam specialised in the study of Communist Eastern Europe. His history dissertation explored the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia, and was titled “‘Our Democracy is Dying’: The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia and its Immediate Aftermath, 1945-1953”. Sam has been awarded a postgraduate bursary at Leeds Beckett, and will begin studying for an MA in Social History in September 2015.

SOURCES

Applebaum, A, (2012), Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56. Allen Lane

Abrams, B (2004) The struggle for the soul of the nation : Czech culture and the rise of communism. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: Maryland.

Abrams, B (2010) ‘Hope Died Last: The Czechoslovak Road to Socialism’ In Tismaneanu, V. Ed. Stalinism Revisited: The Establishment of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press pp.345-367

Cashman, L (2008) ‘Remembering 1948 and 1968: Reflections on Two Pivotal Years in Czech and Slovak History’, Europe-Asia Studies, 60/10, 1645-1658.

C.I.A (1948) ’62 Weekly Summary Excerpt, 27 February 1948, Communist Coup in Czechoslovakia; Communist Military and Political Outlook in Manchuria’[Internet]< https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/assessing-the-soviet-threat-the-early-cold-war-years/5563bod2.pdf>%5BAccessed on 9 April 2015]

Gross, J, ‘The Social Consequences of War: Preliminaries for the Study of the Imposition of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe’, East European Politics and Societies, 3 (1989) pp.198-214.

Gellately, R. (2013) Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kovaly, H. (2012) Under a Cruel Star: My Life in Prague 1941-1968. London: Granta

Langer, J. (2011) Convictions: My Life With A Good Communist. London: Granta.

Lukes, I (1997) ‘The Czech Road to Communism’ In Naimark, N and Gibianskii, L The Establishment of Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe 1944-1949. Westview Press.

Slingova, M (1968) Truth Will Prevail, London: Merlin Press.

Swain G and Swain N (1993) Eastern Europe since 1945. Basingstoke: Macmillan

25 years since the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Last weekend marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event which is remembered today as one of the iconic moments of the East European revolutions of 1989. Of course, the fall of the wall and the capitulation of the communist regime in East Germany did not represent the beginning of the changes that swept the communist bloc during that tumultous year – by 9th November 1989 Solidarity had already achieved electoral success in Poland, and the Hungarian communist party had announced sweeping reforms, proposed democratic elections and opened up their borders with the West – a move that also directly contributed to the final destabilisation of the communist regime in East Germany. Neither did the fall of the wall signal the end of the East European revolutions: the following day Bulgarian leader Todor Zhivkov announced his resignation after 18 years in power, later in November the Velvet Revolution led to the end of communist rule in Czecholovakia and in December the Romanian Revolution resulted in the Christmas Day execution of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena. However, between its construction in August 1961 and its destruction in November 1989, the Berlin Wall came to symbolise the ‘Iron Curtain’ that separated Western Europe from the communist Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, so when the Wall finally crumbled and live images showing thousands of Germans celebrating by hacking at the hated structure with hammers and pick-axes were transmitted around the world, it created one of the most iconic moments of the revolutions of 1989, the collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War. As Soviet foreign policy advisor Anatoly Chernayev recorded in his diary on 10th November 1989: “The Berlin Wall has collapsed. This entire era in the history of the socialist system is over … This is the end of Yalta … the Stalinist legacy and “the defeat of Hitlerite Germany”.

Twenty five years on, the fall of the Berlin Wall is remembered as an iconic moment during the the revolutionary year of 1989.

Although I was still only a child, I do remember the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. I remember sitting transfixed in front of the TV, watching ‘John Craven’s Newsround’ on CBBC, as footage of the collapse of the wall and the first emotional meetings between Germans from East and West was shown. While I wasn’t old enough to really understand what was going on, I do remember the vivid sense that something *really* important was happening – the first sense I ever had of ‘living through history’. That feeling stayed with me over the years, and I have often wondered whether that was the reason why I became so interested in Central and East European history, eventually making a career out of it!

Five years ago, in November 2009, I was also lucky enough to be able to visit Berlin for the 20th anniversary ‘Mauerfall’ celebrations, as giant dominoes were set up following the former route of the Wall, before being symbolically toppled on the evening of 9th November:

Viewed from the Reichstag, giant dominoes snaking through the centre of Berlin – part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in Novembr 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Giant dominoes lined up along the former route of the Berlin Wall, November 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

This year, a different kind of installation – a ‘border of light’ or ‘Lichtgrenze‘ was created in Berlin, comprised of 8000 illuminated balloons that were then released, one by one, on the evening of 9th November 2014:

Although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin, the power of the internet meant I could still watch the release of the balloons and the dramatic firework finale from the comfort of my own sofa on Sunday evening via the official livestream. Granted, it wasn’t as good as actually being in Berlin, but alongside the proliferation of photos and videos posted on Twitter, it was a pretty good substitute!

However, although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin this year, I was able to organise an event to commemorate the 25th anniversary here at Leeds Beckett University, through our Centre for Culture and the Arts. Invited guest speaker Oliver Fritz, author of the critically acclaimed book The Iron Curtain Kid visited and spoke about his experiences of growing up ‘on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall’ in communist-controlled East Berlin, and about witnessing the fall of the Wall in November 1989. Oliver provided some fascinating – and often very humorous – insights into life in communist East Germany, attracting a lively audience comprised of staff, students and members of the public. Oliver’s talk was followed by a screening of the Oscar-winning film The Lives of Others (2007), a critically acclaimed portrayal of a Stasi agent assigned to conduct surveillance on a writer suspected of dissident activities in East Berlin during the 1980s.

Oliver Fritz, author of ‘The Iron Curtain Kid’ talking about his experiences of growing up in East Berlin at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett

Oliver Fritz and Kelly Hignett demonstrating East German speech etiquette to an enthusiastic audience! Photo © Dr. Zoe Thompson.

A special exhibition, produced by Leeds Beckett students studying for a BA in Graphic Arts and Design (working with GAD Senior Lecturer Justin Burns), in collaboration with some of our final year BA History undergraduates was also displayed to mark the event. The impressively detailed and striking exhibition functioned as a visual timeline, spanning the initial division of Germany after WWII until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989:

Oliver Fritz admiring part of the 25th Berlin Wall fall anniversary exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

‘Mini Berlin Wall’ – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Timeline style wall display – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Timeline style wall display – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Two perspectives: 1961 and 1989. Installation displayed as part of 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

‘Bricks from the Berlin Wall’ – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Berlin Wall Bricks' [print] - student artwork displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/bricks-print-crop.jpg?w=620&h=422)

‘Berlin Wall Bricks’ [print] – student artwork displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['25 years since Mauerfall' [print] - student art work displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/2014-11-07-22-43-44.jpg?w=350&h=507)

’25 years since Mauerfall’ [print] – student art work displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Hammering down the Wall' [print] - 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/hammer-pic.jpg?w=324&h=555)

‘Hammering down the Wall’ [print] – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Two Berlins' [print] - 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/tightrope-faces-crop.jpg?w=479&h=325)

‘Two Berlins’ [print] – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

You can read more about the event here.

Finally, the 25th anniversary commemorations have recived a lot of media attention and online coverage. Here is a short collection of some of my favourite features from the past week:

- This great RFERL infographic – 25 Years Later: The European Revolutions – for the ‘bigger picture’ of what was happening in 1989.

- The 25 Years Iron Curtain Twitter feed – who are tweeting short reports about key events that took place in Eastern Europe in 1989.

- This short video on Vine – The History of the Berlin Wall in 60 Seconds

- Special CWIHP documentary collection – 25th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

- The Berlin Wall in Google Street View

- The Guardian’s interactive photo gallery of the Berlin Wall in the Cold War and Now

- The Berlin Wall – Before and After – photos in the Washington Post.

- Lichtgrenze on Vimeo

- A collection of stories from Berliners who Remember the Fall of the Wall and Berlin 1963: three stories of a divided city.

- Timoth Garton Ash’s article about The fall of the Berlin Wall – What it meant to be there

- Reuters photo slideshow – When Berlin Was Two.

- Deutsche Welle Opinion Piece – November 9th 1989: An unforgettable day for Germany, and for Europe.

- 25 years on – different international perspectives about what caused the fall of the wall.

#

Pavement markers showing the route of the former division still run through Berlin today. Photo © Kelly Hignett.‘Everything about everyone’: the depth of Stasi surveillance in the GDR.

The recent NSA scandal has triggered comparisons with the East German Stasi, demonstrating that even twenty five years after the collapse of the GDR the Stasi still act as a a default global synonym for the modern police state. In this blog post, guest author Rachel Clark, a final year History student at Leeds Metropolitan University, explores the intrusive methods used by the Stasi in their ruthless and relentless pursuit to ‘know everything about everyone’ in the GDR.

‘Everything about everyone’: the depth of Stasi surveillance in the GDR.

By Rachel Clark.

The recent NSA whistleblowing scandal has drawn comparisons with the once feared East German Stasi. (Image credit: AP Photo, from http://www.thenation.com/article/174746/modern-day-stasi-state# )

The whistle-blower scandal currently dominating the USA has resulted in some uncomfortable comparisons being drawn between the actions of the US National Security Agency and the activities of the East German Stasi, arguably the most formidable security service in modern European history. One former Stasi officer has even commented that ‘The National Security Agency’s domestic surveillance capabilities would have been ‘a dream come true’ for East Germany. NSA supporters have emphasised the necessary role that the agency plays to protect national security interests, whereas the Stasi’s sole objective was to act as the ‘sword and shield’ of the East German communist party and ensure their continued supremacy. In order to fulfil this role, the Stasi developed an extensive range of highly intrusive methods.

Stasi Surveillance Tactics

The establishment of communist regimes across Eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II led to a severe expansion of domestic security services as these ‘overt socialist dictatorships’ required complete ideological compliance from the populations under their authority. The East German Ministry of State Security (MfS), otherwise known as the Stasi, was founded in 1950, and would soon go on to develop a fearsome reputation both within and beyond the GDR.

The Stasi aimed to rigidly monitor and ruthlessly suppress any potential dissent or non-conformity. In the Stasi mindset, knowledge was power, and inStasiland Anna Funder describes how the Stasi strove to ‘know everything about everyone’, scrutinising not only the political conduct of suspected opponents but also their personal lives, infiltrating leisure clubs and social societies, their working lives, and even studying their sexual habits. The 2006 thriller The Lives of Others depicts Stasi surveillance tactics in East Berlin, as the film’s protagonist, Stasi officer Gerd Wiesler rigorously monitors his allocated target by eavesdropping on and recording their most private moments, including their personal conversations, telephone calls, and even their lovemaking. Gerd Wiesler effectively illustrates how the Stasi operated with no limits to privacy and had no shame when it came to protecting the party and the state.

Stasi tactics involved serious breaches of privacy, but the organization simply operated ‘above the law’. Various methods of comprehensive surveillance and control over communication were utilised by the MfS, including the opening of personal mail and the tapping of telephone calls, and by the 1960s 3,000 Stasi officers had been assigned to telephone surveillance. Personal correspondence was opened religiously, with little effort made to disguise mail that had been tampered with. Julia, a citizen of the former GDR who was placed under intense Stasi surveillance due to her a relationship with an Italian man, described to Funder how her letters used to frequently arrive ripped open, with stickers claiming they had been ‘damaged in transit’ (Stasiland). Recording devices were secretly installed in suspected dissident’s homes and regular ‘home intrusions’ (apartment searches) were conducted while residents were out, although the Stasi often deliberately left discreet signs of their presence, designed to intimidate the individual they were monitoring.

Ulrike Poppe became one of the most heavily targeted individuals in the GDR due to her unrelenting support for democracy, and she was intimidated and harassed by the Stasi on a daily basis. Poppe recalls how Stasi officers often flattened her bicycle tyres and due to their desire to acquire as much information about her as possible, the homes of her friends and acquaintances were bugged and cameras were installed across the street from her apartment. This level of personal persecution was a tactic often utilised against Stasi targets, as they endeavoured to strike fear and unease into all sectors of society. The Stasi’s relentless methods were somewhat of an ‘open secret’ among the GDR populace, most of whom became resigned to living under the ever-watchful eye of the organisation.

Stasi Files

The Stasi kept meticulous records and Stasi files were released to the public in 1992. Image taken from: http://www.theartofgoodgovernment.org/berlinwall.html

Such a wealth of information resulted in the formation of files containing remarkably detailed descriptions of citizen’s lives. After the collapse of communism and the dissolution of the MfS, the Gauck Agency (BStU) seized control of these files and early in 1992 public bodies and individuals were access to these surveillance records. 180 kilometers of files, 35 million other documents, photos, sound documents, and tapes of telephone conversations were released for public viewing. This exposed the depth of observation that East German citizens had been subjected to, highlighting the shocking crimes and breaches of privacy committed by the Stasi. Historian Timothy Garton-Ash was conducting research for his PhD in East Berlin in 1978, and as a western intellectual he was closely observed by the MfS. In 1997, having accessed his file, Garton-Ash authored a book The File: A Personal History, describing his experiences with the Stasi and recording how he had been ‘deeply stirred’ by reading his file, a ‘minute-by-minute record’ of his time in Berlin’. After reading her file, Ulrike Poppe was also surprised by the depth of Stasi knowledge, everything had been recorded, no matter how trivial, as her file contained a record of her every movement and was full of ‘just junk’.

Ardagh estimates that secret files were kept on about one citizen in three, highlighting the enormity of the Stasi library. In order to gather such extensive amounts of information, the MfS established an immense network, comprised of both fulltime, paid Stasi officers and a large quantity of informers. At the height of Stasi dominance shortly before the collapse of communism in 1989, estimates suggest there were a staggering 97,000 people employed by the MfS with an additional 173,000 informers living amongst the populace, resulting in an unprecedented ratio of one Stasi officer for every sixty-three individuals. If unpaid informers are included in these figures, the ratio could have been as high as one in five. (Figures from Ardagh, Germany and the Germans and Funder, Stasiland).

Stasi Informers

It was the widespread recruitment of Inoffizielle Mitarbeiters (IM’s, or ‘unofficial collaborators’), that allowed the Stasi to construct such an impressive

Ulrike Poppe was subjected to intense Stasi surveillance and frequent harassment due to her political views. Image taken from: http://www.aufarbeitung.brandenburg.de/media_fast/bb1.a.2882.de/Ulrike_Poppe.jpg

army of spies and conduct such intense levels of surveillance. The recruitment of informers enabled the Stasi to infiltrate all aspects of daily life. In the GDR ‘everyone suspected everyone else, and the mistrust this bred was the foundation of social existence’ (Stasiland p.28). Former citizens of the GDR often say that the most distressing element of retrieving ones Stasi file was the revelation that trusted friends, family members and colleagues had been secretly relaying information about them to the MfS. Though such a revelation is obviously upsetting, Dennis argues that a large number of IM’s were blackmailed or coerced by the Stasi (Stasi, p.243). Potential IM’s were subject to strict Stasi scrutiny to ensure they were ‘appropriate’ targets and all of their personal details would be closely examined, including their sexual behavior. Any potential ‘flaw’ uncovered could serve as a means of blackmail to ‘persuade’ potential recruits to inform on others; again illustrating the famed Stasi obsession for personal information.

A Modern Day Stasi?

The Stasi operated with cunning and coercion and their intense levels of intimidation and surveillance successfully created a culture of fear in the GDR. Following the East German uprising of June 1953 the GDR was often perceived as ‘one of the most quiescent’ of the east bloc states (Anatomy of a Dictatorship, p.5) and it is significant that there were no further outbreaks of mass political stability until communism collapsed in November 1989. The fearsome reputation of the East German state security survived the collapse of communism and the end of the GDR itself, as shown by the fact that contemporary security establishments such as NSA are likened to a ‘modern-day Stasi State’. In today’s increasingly digital age, some of the old Stasi surveillance tactics such as opening letters seem a little out-dated, but the digital advances of the twenty first century pose some interesting debates as it can be suggested that today’s technological capabilities may succeed is making the modern populace as vulnerable to personal infiltration as those who lived under the Stasi. Perhaps we should consider whether hacking email accounts, Facebook ‘stalking’, CCTV surveillance and GPS tracking are really so far-removed from tearing open letters and tailing individuals as they go about their daily activities?

About the Author:

Rachel Clark has recently completed her BA in History at Leeds Metropolitan University and will graduate with First Class Honours later this month. During her final year of study, Rachel studied the history of twentieth century East Central Europe, specialising on the role of the Stasi for one of her research essays. Her final year dissertation, which researched the treatment of shell-shock in the First World War, was awarded the class prize. Rachel plans to spend the next year travelling and hopes to continue her academic studies at postgraduate level when she returns.

Suggested Reading:

Curry, C. (2008) ‘Piecing Together the Dark Legacy of East Germany’s Secret Police’, Wired Magazine

Dennis, M. (2003) The Stasi: Myth and Reality Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Fulbrook, M. (1995) Anatomy of a Dictatorship: Inside the GDR 1949-1989 Oxford: Oxford University Press. .

Funder, A. (2003) Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall London: Granta Publications.

Funder, A. (2007) ‘Tyranny of Terror’, The Guardian

Garton-Ash, T. (2007) ‘The Stasi on Our Minds’, New York Review of Books

Ghouas, N. (2004) The Conditions, Means and Methods of the MfS in the GDR; An Analysis of the Post and Telephone Control Gottingen: Cuvillier Verlag.

Koehler, J, O. (1999) Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police Colorado: Westview Press.

Pittaway, M. (2004) Brief Histories: Eastern Europe 1939-2000 London: Hodder Arnold.

BASEES ICCEES 2013

Last weekend (6th-7th April) I attended the 2013 BASEES/ICCEES European Congress held at Fitzwilliam College in Cambridge. Unfortunately, teaching responsibilities and other constraints meant I missed the opening afternoon/evening on Friday 5th and the final panels taking place on the morning of Monday 8th. This was my third year as a participant at BASEES (you can see my report on last year’s conference HERE) and it was also my second year live tweeting from my twitter account @kellyhignett using the official conference hashtags: #euroiccees #basees. The annual BASEES conference brings together researchers working on all manner of topics related to Slavonic and East European studies, past and present, and has quickly become one of the highlights of my conference calender! The broad theme of this year’s congress was ‘Europe: Crisis and Renewal’, which encompassed a range of panels covering topics as diverse as cultural conflict in late Imperial Russia, re-thinking Cold War Eastern Europe, contemporary Balkan politics, the economics of Central Asia and the politics of healthcare in the post-Soviet space. As in previous years, the biggest problem I faced was trying to decide which of the intriguingly-titled panels to attend!

The first panel I attended on Saturday 6th focused on ‘New Perspectives in Cold War Studies’. In addition to great papers about East-West interaction during the Cold War by Sari Autio-Sarasmo and ‘Interactive Socialism’ by Katalin Miklossy, I particularly enjoyed Melanie Ilic’s paper, discussing her experience of interviewing and recording the life stories of several high profile Soviet women. Melanie’s new book Life Stories of Soviet Women will be published this August, featuring an impressive range of interviewees include one of Khrushchev’s daughters! She is also currently editing a collection relating to the ethics of oral history and memory studies, which I am contributing a chapter to, in relation to my own work on petty criminality in late-socialist East Central Europe.

A second panel, ‘New Research on Cold War Eastern Europe’, also contained an interesting mix of papers.Andru Chiorean discussed the ways in which new archival evidence is prompting a re-evaluation of role played by the Romanian censorial agency in regulating the output and content of publications after 1948, highlighting the need for researchers to incorporate the perspectives of both censor and victim. Patrick Hyder Patterson delivered a fascinating paper about socialist brand packaging in the East bloc, followed by an interesting discussion about the ‘afterlives’ of these brands, many of which are remembered fondly today (think Ostalgie and the film Good Bye, Lenin!). I’ve read Patterson’s book Bought and Sold: Living and Losing the Good Life in Socialist Yugoslavia and can recommend it. Finally, Kristian Nielsen argued the need to reconsider the economic aspects of Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik.

I particularly enjoyed both keynote speeches on the Saturday evening, given by Sabrina Ramet and Luke Harding. First up was Sabrina Ramet, whose talk ‘Religious Organizations and the Legacy of Communism in East Central Europe’ was insightful and engaging. Ramet began by linking calls for ‘re-evangelisation’ in post-communist east Europe with the popular desire for a return to more conservative social norms including discouraging divorce, contraception, abortion and homosexuality. She also discussed how the post-communist religious resurgence gave rise to a form of ‘gigantomania’ in the former East bloc, with the construction of elaborate places of worship, religious icons and statues (including massive figures of Mother Theresa and Jesus – with three different cities (one in Slovakia, two in Poland) all competing to build the world’s largest statue of Jesus and the world’s tallest cross erected in Macedonia!). The bulk of Ramet’s paper however, focused on the evidence of widespread collaboration between various religious leaders and the secret services that have emerged with the opening of communist-era archives. The available evidence shows numerous instances of Orthodox priests in Romania passing information gleaned from the confessional to the Securitate, while Ramet suggests that 10-25,000 Catholic clergy acted as informants in Poland, while also acknowledging that there were some cases of ‘fake files’, planted to implicate innocent priests. After a quick break for refreshments during the wine reception (always a conference favourite!) and dinner, I returned to listen to Guardian Reporter and former Russian Correspondent Luke Harding discussing the experiences that formed the basis of his book Mafia State, in conversation with Glasgow University’s Stephen White. Harding too, was a very engaging speaker, likening his experiences in Russia to a bad spy thriller, but ‘without the Aston Martin or the beautiful Bond girls’, and describing Putin’s Russia as a ‘clever, adaptive, post-modern autocracy’ where corruption has flourished. The informal conversational style worked well, and was followed by a range of lively, probing questions from the audience.

I was up early on the bright and sunny Sunday morning to present my own paper, entitled ‘Doing Drugs Behind the Iron Curtain‘, alongside a fascinating paper about naratives of Kosovan wartime exile and Albanian nationalism, given by Erida Prifti and Nicholas Crowe from the University of Vlore in Albania. My own paper was taken from a longer article I’m currently working on, which will be completed and submitted for publication this summer. This article explores levels of drug abuse and the development of domestic drug markets in East Central Europe between 1960s-1980s. In a nutshell though, the key points of my BASEES paper were as follows:

- Although the regimes in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland all noted rising levels of drug abuse from the 1960s this was largely denied and downplayed through a campaign of misinformation, censorship and propaganda

- However, this official policy of ‘silence and inaction’ not only had negative consequences with regards to the lack of information, education, legislation and specialist healthcare available for drug addicts, but in many ways also faciitated the development of a thriving domestic market for the production and supply of illegal drugs.

- The two main sources of supply were narcotics acquired from state healthcare (either via forged prescriptions or stolen by staff in hospitals, pharmacies and Doctors surgeries) and domestic production of a range of opium and amphetamine based drugs, including Pervitin (Czechoslovakia) and Kompot (Poland), which were sold on the black market.

- By the 1980s more organised, professional criminal networks began to operate in the drugs trade, which, according to law enforcement reports, was increasingly dominated by ‘professional manufacturers and pushers’. I’ve also discovered evidence of international links with the wider global drugs trade, including gangs operating in the Middle East, South America, India, West Africa and Turkey, who were engaged in a range of drug smuggling operations through the East Bloc and across the Iron Curtain, although the domestic market in East Central Europe remained dominated by domestically produced and soirced drugs until the collapse of communism in 1989.

Before travelling home late on Sunday afternoon, I was also able to attend panels on ‘History, Narratives and Politics’, comparing contemporary Poland and Russia, and ‘Opposition, Terror and Imprisonment in Interwar Russia’, where I particularly enjoyed Ian Lauchlan’s discussion about the rise and fall of notorious Soviet Security chief Felix Dzerzhinsky and Mark Vincent’s insights into the fascinating subject of Urki (criminal) courts in the Soviet Gulag camps, as protrayed in memoirs written by former camp inmates.

Finally, I’d like to send a special shout out to the team from online magazine Crossing the Baltic, who I was lucky enough to meet at the conference. Check out their great website HERE, and you can also follow them on Twitter @CrossingBaltic !

Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe

In this, the final post in this year’s student showcase, Christian Parker considers the slow but steady growth in dissent and organised opposition in Eastern Europe in the decades following the Prague Spring. While the majority of citizens adopted an attitude of outward conformity, a small but vocal minority bravely continued to speak out against various aspects of communist rule, even in the face of sustained state repression and persecution. The state authorities adopted a range of coercive means to contain and marginalise dissent and non-conformity in both the political and the cultural sphere, however ultimately they were unsuccessful in their attempts to quell opposition to communist rule.

Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe.

By Christian Parker

The failure of Alexander Dubcek’s attempt to develop ‘socialism with a human face’ and the forcible crushing of the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia in August 1968 was the catalyst for an ‘era of stagnation’ in Eastern Europe. In a speech made to the Polish Communist Party on 12th November 1968, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev justified the recent military intervention in Czechoslovakia and confirmed that any future attempts to deviate from the ‘common natural laws of socialist construction’ would be treated as a threat.[1] The message was clear: any significant reforms to the existing system would not be tolerated. As Tony Judt notes, this ‘Brezhnev Doctrine’ set new limits on manoeuvrability and freedom within the Eastern bloc, each state ‘had only limited sovereignty and any lapse in the Party’s monopoly of power might trigger military intervention’.[2] As long as the Soviets were prepared to maintain communism in Eastern Europe by force, any attempt at challenging the status quo appeared futile so most people adopted a policy of outward conformity and passive acceptance towards communism. However, dissent and non-conformity continued to exist in Eastern Europe, and the authorities employed extensive repression against dissidents, developing a range of coercive tactics to ensure dissent and opposition remained on the fringes of socialist society.

Charter 77 and the Birth of Organised Opposition

Perhaps the most important dissident movement to emerge in Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Prague Spring was the Charter 77 group. Charter 77 was initially formed in response to the arrest of a popular Czechoslovakian band ‘The Plastic People of the Universe’ for musical non-conformism and social subversion, after the band wrote to dissident playwright Vaclav Havel (previously famous for his 1975 Open Letter to Husak which protested the pervasive fear and ‘fraudulent social consciousness’ dominating life in Czechoslovakia after the Prague Spring), requesting his help to campaign for greater tolerance in both the political and cultural spheres.[3]

Charter 77 therefore sought to establish a ‘constructive dialogue’ with the communist party, aimed at securing a range of human rights and individual freedoms, including freedom from fear and freedom of expression which the movement demonstrated were ‘purely illusory’ in communist Czechoslovakia.[4] The movement gained further impetus from the fact that the Czechoslovakian government had recently signed the Helsinki Accords, promising to uphold ‘civil, political, economic, social, cultural…rights and freedoms’.[5]

Signatures for Charter 77 – calling on the Czechoslovakian communist party to uphold commitments to basic freedoms and human rights. Signatories were harrassed and persecuted in a variety of ways.

On its initial publication in January 1977, the Charter initially bore 243 signatures, including those of Vaclav Havel, Pavel Landovsky and Ludvik Vaculik. The state acted quickly in an attempt to prevent the campaign gaining momentum by arresting Havel, Landovsky and Vaculik whilst they were en route to the federal assembly, where they planned to deliver a copy of the Charter. The state’s retaliation to Charter 77 was wide and menacing; leading figures associated with the movement were arrested and imprisoned and signatories were targeted via a wide range of other means including arrest, intimidation, dismissal from work, denial of schooling for their children, suspension of driver’s licenses and the threat of forced exile and loss of citizenship – Geoffrey and Nigel Swain note that by the mid-1980s over 30 ‘Chartists’ had been deported, including Zdenek Mlynar, former secretary of the Czechoslovakian communist party.[6] Charter 77 backed the ‘Underground University’ (an informal institution that attempted to offer free, uncensored cultural education) but lecturers were frequently interrupted by policemen, and leading figures including philosopher Julius Tomin, were harassed and assaulted by ‘unknown thugs’. Attempts were also made to pressure workers into signing anti-Charter resolutions, though as the state representatives failed to give the workers a copy of the Charter so they could see what they were signing against, the majority refused.[7]