Women and Repression in Communist Czechoslovakia

Today’s blog post, written for International Women’s Day 2016, relates to my current research into women’s experiences of repression in communist Eastern Europe, with a particular focus on Czechoslovakia 1948-1968, during the period of Stalinist terror and its immediate aftermath.

The vast majority of the 90,000 – 100,000 Czechoslovak citizens who were prosecuted and interned for political crimes between 1948-1954 were men; only between 5,000 – 9,000 (5-10%) were women. These women were held in numerous different prisons and forced labour camps across Czechoslovakia, where they frequently experienced poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene and medical care and enforced labour, while enduring physical and psychological violence, abuse and humiliation at the hands of the penal authorities. Beyond this, however, hundreds of thousands of other Czechoslovakian women also became ‘collateral’ victims of state-sanctioned repression during these years. The Czechoslovakian Communist Party actively pursued a policy of ‘punishment through kinship ties’, so while family members of those incarcerated for political crimes were not necessarily arrested themselves, they were considered ‘guilty by association’. As men comprised the majority of political prisoners, it was usually the women who were left trying to hold their families together and survive in the face of sustained political and socio-economic discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

The growth in published memoirs and oral history projects such as Paměť Národa and Političtívězni.cz in post-communist Czech Republic and Slovakia have encouraged more victims of repression to record their stories. However, women’s experiences of political repression in communist Czechoslovakia remain under-researched and under-represented in the historiography. It is often suggested that women are generally more reluctant to share personal accounts of traumatic experiences, in comparison with their male counterparts. For example Historian Tomáš Bursík’s study of Czechoslovakian women prisoners Ztratili jsme mnoho casu … Ale ne sebe! notes that in many cases ‘Women do not like to return to their suffering, that misfortune they affected, the humiliation that followed. They do not want to talk about it’. In her own account of imprisonment in communist Czechoslovakia, Krásná němá paní, Božena Kuklová-Jíšová also explained that:

‘We women are very often criticized for not writing about ourselves, about our fate. Perhaps it is because there were some moments which were very humiliating for us; or because in comparison to the many different brave acts of men, our acts seem so narrow-minded. But the main reason is that we have difficulties presenting ourselves to the world’.

This reticence extends to many women who experienced collateral or secondary repression, such as Jo Langer, who despite being subjected to sustained political harassment and socio-economic discrimination including loss of employment and forced relocation when her husband Oscar was arrested and interned 1951-1960, described how, upon receiving the first full account of her husband’s traumatic experiences in the camps after his release, she felt ‘shattered and deeply ashamed of having thought myself a victim of suffering’ (You can read more about Jo Langer’s autobiography Convictions: My Life with a Good Communist in my previous blog post HERE)

However, the inclusion of women’s narratives make an important contribution to the historiography, broadening and deepening our understanding of terror and repression in communist Eastern Europe. A number of women who endured political repression have shared their stories, which not only document their suffering at the hands of the Communist Party but are also testimony to their strength, resistance and will to survive. Through their narratives, these women are able to present themselves simultaneously as both victims and survivors of communist repression.

Today then, it seems fitting to mark International Women’s Day 2016 by briefly highlighting two examples to pay tribute to the many strong, spirited and inspiring women who feature in my own research.

Dagmar Šimková

“The screeching seagulls are flying around me. I am so free, I can walk barefoot. And the waves wash away traces of my steps long before a print could be left”.

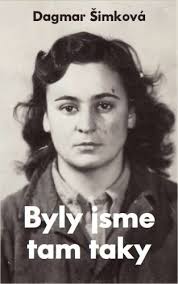

Dagmar Simkova’s arrest, official photograph (1952). Source: http://zpravy.idnes.cz/autorka-svedectvi-o-zenskych-veznicich-krasna-a-inteligentni-dagmar-simkova-by-se-dozila-80-let-i1u-/zpr_archiv.aspx?c=A090522_114346_kavarna_bos

Dagmar Šimková’s autobiographical account of her experiences in prison Byly jsme tam taky [We were there too] is arguably one of the strongest testimonies of communist-era imprisonment to emerge from the former east bloc. Šimková’s family became targets after the communist coup of 1948 due to their ‘bourgeois origins’ (her father had been a banker). Their villa was confiscated by the Communists, while Dagmar and her sister Marta were denied access to university. While Marta fled Czechoslovakia in 1950, Dagmar became involved in resistance activities, printing and distributing anti-communist leaflets and posters mocking the new Czechoslovakian leader, Klement Gottwald. In October 1952, following a failed attempt to help two friends avoid military service by escaping to the West, she was arrested, aged 23, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Between 1952 – 1966 Šimková passed through various prisons and labour camps in Czechoslovakia: in Prague, Pisek, Ceske Budejovice and Opava. In 1955 she even briefly escaped from Želiezovce, a notoriously harsh agricultural labour camp in Slovakia. Sadly, her freedom was shortlived: she was found sleeping in a haystack at a nearby farm two days later, recaptured and returned to Želiezovce, where an additional three years was added to her existing prison term as a punishment.

Dagmar Simkova’s book Byly Jsme Tam Taky [“We Were There Too”]

From 1953, Šimková was held in Pardubice Prison near Prague, in the women’s department ‘Hrad’ (Castle), which was specially created to house 64 women who were perceived as being the ‘most dangerous’ political prisoners, and segregate them from the main prison population. Here, Šimková participated in several organised hunger strikes to demand better conditions for women prisoners. She was also an active participant in the ‘prison university’ founded by former university professor Růžena Vacková, who gave secret lectures on fine art, literature and languages to her fellow prisoners. Šimková later described how ‘We devoured every word. We tried to remember, and understand, like the best students at universities’. Some of the women even managed to compile some lecture notes into a small book which was secretly hidden, before being smuggled out of Pardubice in 1965. This book is currently held in the Charles University archives.

After a total of fourteen years incarceration, Dagmar Šimková was finally released in April 1966, aged 37. Two years later, during the liberalisation of the Prague Spring in 1968 she was instrumental in establishing K 231, the first organisation to represent former political prisoners in Czechoslovakia. Following the Soviet invasion to halt the Czechoslovak reforms, Šimková emigrated to start a new life in Austrialia, where she completed two University degrees, worked as an artist, prison therapist and even trained as a stuntwoman! She also worked with Amnesty International , continuing to campaign for better prison conditions until her death in 1995.

Heda Margolius Kovály

Heda Margolius Kovaly. Source: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/dec/13/heda-margolius-kovaly

Heda Margolius Kovály’s memoir, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 remains one of the most damning accounts of the violence and repression that characterised mid-twentieth century central and eastern Europe. Heda’s incredible life story spans the Nazi concentration camps, the devastation of WWII, the communist coup and the post-war Stalinist terror in Czechsolovakia. Having survived Auschwitz, Heda escaped during a death march to Bergen-Belsen and managed to make her way home to Prague. After the war, she was reunited with her husband Rudolf Margolius, who was also a concentration camp survivor, and a committed communist. Following the Communist coup of February 1948, Rudolf served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, only to quickly fall victim to the Stalinist purges. Rudolf was arrested on 10 January 1952, brutally interrogated and forced to falsely confess to a range of ‘crimes’ including sabotage, espionage and treason. He was subsequently convicted as a member of the alleged ‘anti-state conspiracy’ group led by former General Secretary, Rudolf Slansky, in Czechoslovakia’s most infamous show trial. In December 1952, Rudolf was executed, along with 10 of his co-defendents.

Following Rudolf’s arrest, Heda described how ‘Suddenly, the world tilted and I felt myself falling … into a bottomless space’ . She was left to raise their young son, Ivan, while fighting to survive in the face of sustained state-sanctioned repression. She was swiftly fired from her job at a publishing house, and was forced to work extremely long hours for pitifully little pay, while living on ‘bread and milk’ in order to make enough to cover their basic needs. Her savings and most of her possessions were confiscated, and she and Ivan were forced to leave their home and move to a single room in a dirty and dilapidated apartment block on the outskirts of Prague, where it was so cold that ice formed inside during the winter months, and cockroaches ‘almost as large as mice’ crawled up the walls. Abandoned by most of her former friends, Heda describes how she became a social pariah who was treated ‘like a leper’. At best, former friends and acquaintances would ignore her when they passed in the street, while others would ‘stop and stare with venom’ sometimes even spitting at her as she walked by.

The strain of living under these conditions caused Heda to become critically ill, but she was initially denied medical treatment. When she was finally admitted to hospital she had a temperature of 104 and a long list of ailments, leading the doctor who treated her to compare her to a newly released concentration camp survivor. It was while she was recovering in hospital that she heard Rudolf’s trial testimony broadcast on the radio, and she listened to her husband monotonously admit to ‘lie after lie’ as he recited the script he had been forced to learn. Forcibly discharged from hospital before she was fully recovered, Heda was so weak that she had to crawl ‘inch by inch’ from the front door of her apartment block to her bedroom, where she spent several weeks following Rudolf’s execution ‘motionless, without a thought, without pain, in total emptiness … lying in my bed as if it were a coffin’.

‘Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968’ is Heda Margolius Kovaly’s account of surviving Nazi and Communist persecution.

Nevertheless, Heda regained her strength. Her son Ivan later described how, even in the face of sustained persecution ‘Heda survived through her determination and managed to look after us both’. She continued to maintain Rudolf’s innocence and fought to clear his name, writing endless letters and attempting to arrange meetings with various communist officials, most of whom refused to see her. Following Rudolf’s execution, she dared to publicly mourn him by dressing completely in black, in a deliberate challenge to the Communist Party. After she remarried in 1955, she continued to campaign for Rudolf’s full rehabilitation. In April 1963, she was finally summoned to the Central Committee where Rudolf’s innocence was privately confirmed, and Heda was asked to write a ‘summary of losses’ suffered as a result of his arrest and conviction, so that she could apply for compensation. In Under a Cruel Star, she described how:

‘I sat down at my typewriter and typed up a list:

– Loss of Father

– Loss of Husband

– Loss of Honour

– Loss of Health

– Loss of Employment and Opportunity to Complete Education

– Loss of Faith in the Party and JusticeOnly at the end did I write:

– Loss of Property’.

Upon presentation of this list, the Communist officials responded in confusion:

‘”But you must understand that no one can make these losses up to you?”. “Exactly” I said “That’s why I wrote them up for you, So that you know that whatever you do you can never undo what you have done … you murdered my husband. You threw me out of every job I had. You had me thrown out of a hospital! You threw us out of our apartment and into a hovel where only by some miracle we did not die. You ruined my son’s childhood! And now you think you can compensate for that with a few crowns? Buy me off? Keep me quiet?”.’

Following the failed Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Heda left Czechoslovakia and settled in the USA with her second husband, Pavel Kovály. There, she continued to forge a successful career as a translator in addition to working as a librarian in the international law library at Harvard University. Heda Margolius Kovály died in 2010, aged 91. In addition to her personal memoir Under A Cruel Star, an English-language translation of Heda’s novel Nevina [Innocence] was recently published in 2015 – which I can also highly recommend!

The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia

THE RISE OF COMMUNISM IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA – BY SAM SKELDING

On 25th February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, led by Klement Gottwald, officially gained full power over the country. The communist rise to power was dubbed ‘Victorious February’ during the Communist era, and was celebrated each year, although since 1989 it has been more popularly referred to in slightly less positive terms, as ‘the February Coup’. It had taken just three short years for the communists to gain full control of Czechoslovakia following the end of World War II, but, by the standards of other East European countries, they were fairly late in establishing power. Just how did the communists managed to rise to the top in a country that had previously been heralded by many as a beacon of democracy and perceived as one of the most ‘Western oriented’ countries within central and eastern Europe? This article will explore some of the different factors that combined to create a climate favourable to the Communist Party’s ascension to power in Czechoslovakia after World War II.

WWII AND AFTER

Eastern Europe bore some of the worst experiences of World War II. It was here in the ‘bloodlands’ of Europe that the scars the war left behind were felt most keenly, and Czechoslovakia was no exception. Bradley Abrams has argued that WWII served ‘as both a catalyst of, and a lever for communism [in Czechoslovakia] … creating the intellectual and cultural preconditions for the Communist Party’s rise to total power’ after 1945 (Abrams 2004, p.105).

Although Czechoslovakia recovered most of its pre-WWII territory after 1945, in other ways things looked very different. Firstly, the ethnic and social makeup of Czechoslovakia changed significantly as a result of World War II. During the years of Nazi dominance, German ‘colonists’ began to move into the country whilst many Czechs and Slovaks were deported to forced labour camps or murdered. By 1945, 3.7 percent of the pre-war Czech population had died, including more than a quarter of a million Czechoslovakian Jews, who perished in the concentration camps (Applebaum, 2012, p.10). At the end of the war there was further significant population movement as President Benes authorised the organised expulsion of most of the 3 million ethnic Germans and Hungarians who were resident in Czechoslovakia, whilst thousands of other survivors gradually returned from labour and concentration camps. The decimation of various minority groups (including Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Jews and Roma) meant that following the end of the war, Czechs and Slovaks comprised 90% of the country’s population. This led to heightened nationalism which was subsequently manipulated by the Communist Party, ‘since they could take credit for providing opportunities for mobility and for satisfying nationalist aspirations.’ (Gross, 1989, p.203).

Economically, Czechoslovakia was also transformed by the war. During the years of Nazi occupation and dominance, many businesses were nationalized as the economy was reoriented towards the German war effort, turning Czechoslovakia into more of a ‘closed market’. When the war ended, Czechoslovakia retained a semi-nationalised domestic economy with few remaining international trade links, circumstances which made it easier for the Soviet Union to dominate Czechoslovakia’s post-war economic recovery, which ultimately, laid the groundwork for the post-war shift to Soviet style ‘central planning’. This is illustrated by the fact that, at the end of the War, returning Czechoslovakian President Eduard Benes asked Klement Gottwald, leader of the Communists, to work with the Social Democrats to prepare a decree to nationalise the remaining Czechoslovakian industry (a policy later evidenced in the April 1945 Košice Programme), which met little political opposition.

Czechoslovakia’s international relations also underwent a significant shift after 1945. The perceived failure of their previous political reliance on the West was confirmed after Czechoslovakia became the most famous victim of appeasement with the 1938 Munich agreement (which famously ceded part, and eventually all, of Bohemia to Germany), creating strong feelings of bitterness and insecurity.

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

—Neville Chamberlain, 27 September 1938.

British Prime Minister Neville Chaimberlain’s declaration that the Munich agreement, ceding control over Czechoslovakian territory to Hitler, would secure ‘peace in our time’. Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/nevill3.jpg

Cashman has subsequently argued that, in many ways, ‘the events of 1938 paved the way for the imposition of communism in Czechoslovakia.’ (Cashman, 2008, p.1647). This shift was later compounded when it was the Soviet Red Army who arrived to liberate most of Czechoslovakia from German control in 1945. The fact that it was the Soviets who, as Winston Churchill famously acknowledged, had ‘torn the guts out of Hitler’s war machine’ and secured Czechoslovakia’s freedom, increased Communist prestige in Czechoslovakia. The power and brutality many Czechoslovaks experienced at the hands of the Red Army during and after their liberation (in Czechoslovakia, as elsewhere in ‘liberated’ Eastern Europe, numerous cases of theft, violence and rape committed by Soviet soldiers were recorded) created an aura of fear and admiration around the USSR, as Applebaum remarked ‘The Red Army was brutal, it was powerful and it could not be stopped’ (Applebaum, 2012, p.32).

Finally, there was also widespread popular enthusiasm for social change in Czechoslovakia, which broadly supported a general political shift to the left and towards a more radical, socialist agenda at the end of World War II. Jo Langer described the change in public feeling after 1945, as ‘now the task was to erase the interruption and effects of the war and to help this country ahead on the old road to an even better future’ (Langer, 2011, p.27) while Marian Slingova suggested that ‘socialism in one form or another was the goal for many in those days. In Czechoslovakia, a revolution was in progress.’ (Slingova, 1968, p.40). Heda Margolius Kovaly explained how many who had lived through World War II ‘came to believe that Communism was the very opposite of Nazism, a movement that would restore all the values that Nazism had destroyed, most of all the dignity of man and the solidarity of all human beings’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.64). This all translated into increased levels of support for the Communist Party, who won 114 out of 300 contested seats, and 38 % of the popular vote in the May 1946 election, which, coupled with the support of their socialist allies, gave them a slim political majority of 51%. Robert Gellately has acknowledged that while non-communists were ‘shocked’ by this result, they ‘admitted that the [Czechoslovakian] elections were relatively free and not stolen, as they were elsewhere in Eastern Europe’ (Gellately, 2013, p.233).

THE COMMUNIST PATHWAY TO POWER

Following World War II, a National Government was formed in Czechoslovakia, comprised of 25 ministers, 9 of whom were Communist Party members. From the outset, the Communists were in an influential position, controlling some of the most important government ministries, with a political mandate to launch a sweeping programme of post-war, reform, with explicitly socialist and nationalist aims. Several key post-war politicians, including President Eduard Benes and Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, initially hoped they could work with the communists, while holding out hope that the Western powers would not simply stand by whilst Czechoslovakia fell to Soviet control, despite their bitter experience in 1938 (Lukes, 1997, p.255).

While many Czechoslovakians broadly supported the communist agenda, they hoped for the freedom to develop their own, independent, ‘national road to socialism’. However, between 1946-1948, the Czechoslovakian communists came under increasing Soviet pressure, both to secure sole power, and to conform to Stalinist-style socialism. In July 1947, Stalin’s show of displeasure with the Czechoslovak government’s initial willingness to accept U.S. Marshall Aid forced an immediate reversal of their decision, firmly illustrating the nature of the relationship between the two states. Czechoslovakian Foreign Minister (and non-communist) Jan Masaryk summed up his feelings, about the enforced refusal of Marshall Aid, when he declared that : “I went to Moscow as the Foreign Minister of an independent sovereign state; I returned as a lacky of the Soviet Government.”’ (Lukes, 1997, p.251). Stalin also used the founding conference of the Cominform in September 1947 to publicly criticise the French, Italian and Czechoslovakian Communist Parties for ‘allowing their opportunity to seize power to pass them by’, while the subsequent expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform in June 1948 sent a clear signal to the Czechoslovak communist leadership that the “national roads” policy was no longer supported by the Soviets.

Portraits of Klement Gottwald and Joseph Stalin at a 1947 meeting of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Gottwald_%26_Stalin.jpg

The mechanisms and intrigues surrounding the communist seizure of power in Czechoslovakia have been well documented. During 1947 – 1948 the Communist Party positioned themselves tactically, and one CIA intelligence report recognized that, ‘Having won the key cabinet positions in the May 1946 elections … the Communists have since steadily extended their control of the positions necessary for seizure of the government.’ (CIA, 1948).

By 1948, it appeared that the tide was starting to turn against the Communists, as their coalition partners became increasingly critical of their political tactics. In January 1948, controversy erupted after the communist controlled Minister of the Interior sacked a number of police officials who were not Communist Party members, leading their coalition partners to call for a full cabinet investigation Following this, on 10th February 1948, the socialist minister for the Civil Service won government support for a pay deal that had been strongly opposed by both the communists and the trade unions. However, Klement Gottwald successfully delayed the cabinet from returning to this issue until finally, on 20th February 1948, government ministers from the National Socialists, People’s Party and Slovak Democrats all resigned, in the hope of forcing new elections to reduce the communist’s influence in government. However, the Social Democratic ministers chose to side with the communists and refused to resign, which meant that together the two parties retained over half of the seats in parliament. Gottwald’s position was strengthened by the outbreak of large pro-communist demonstrations in Prague – largely orchestrated by the communists, but with some degree of popular support – so that rather than calling new elections, on 25th February President Benes agreed to the formation of a new government, dominated by the communists and their socialist allies.

As Klement Gottwald triumphantly addressed the crowds, Heda Margolius Kovaly recalled one elderly man’s reaction ‘the old gentleman was standing at the window, looking down at the crowded street. He did not even turn around to greet me. He said, very quietly, “This is a day to remember. Today, our democracy is dying” … Out in the street, the voice of Klement Gottwald began thundering from the loudspeakers.’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.74).

Pro-Communist demonstrations in Prague, February 1948. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Agitace-1947.jpg

Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader Klement Gottwald, addressing the crowds in Wenceslas Square, Prague, on 25 February 1948. Source: https://www.private-prague-guide.com/wp-content/klement_gottwald.jpg

Within weeks the socialists had agreed to formally merge with the communists and the subsequent elections in May 1948 (which were considerably less free than those of 1946!) resulted in the Communist Party gaining over 75 percent of the seats) and on 9 May 1948 a new constitution defined Czechoslovakia as a ‘People’s Republic’ (Swain & Swain, 1993, p64). A one party state had been created in Czechoslovakia, which was rapidly brought under firm Soviet control. From 1948 the Communists were forced to abandon any remaining efforts to retain ‘national’ socialism in Czechoslovakia, in favour of ensuring their country firmly fitted the Stalinist mould.

You can hear more about the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia in this video from the US National Archives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAM SKELDING recently completed his BA (Hons) in History at Leeds Beckett University and will graduate in July 2015. During his final year of study, Sam specialised in the study of Communist Eastern Europe. His history dissertation explored the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia, and was titled “‘Our Democracy is Dying’: The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia and its Immediate Aftermath, 1945-1953”. Sam has been awarded a postgraduate bursary at Leeds Beckett, and will begin studying for an MA in Social History in September 2015.

SOURCES

Applebaum, A, (2012), Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56. Allen Lane

Abrams, B (2004) The struggle for the soul of the nation : Czech culture and the rise of communism. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: Maryland.

Abrams, B (2010) ‘Hope Died Last: The Czechoslovak Road to Socialism’ In Tismaneanu, V. Ed. Stalinism Revisited: The Establishment of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press pp.345-367

Cashman, L (2008) ‘Remembering 1948 and 1968: Reflections on Two Pivotal Years in Czech and Slovak History’, Europe-Asia Studies, 60/10, 1645-1658.

C.I.A (1948) ’62 Weekly Summary Excerpt, 27 February 1948, Communist Coup in Czechoslovakia; Communist Military and Political Outlook in Manchuria’[Internet]< https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/assessing-the-soviet-threat-the-early-cold-war-years/5563bod2.pdf>%5BAccessed on 9 April 2015]

Gross, J, ‘The Social Consequences of War: Preliminaries for the Study of the Imposition of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe’, East European Politics and Societies, 3 (1989) pp.198-214.

Gellately, R. (2013) Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kovaly, H. (2012) Under a Cruel Star: My Life in Prague 1941-1968. London: Granta

Langer, J. (2011) Convictions: My Life With A Good Communist. London: Granta.

Lukes, I (1997) ‘The Czech Road to Communism’ In Naimark, N and Gibianskii, L The Establishment of Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe 1944-1949. Westview Press.

Slingova, M (1968) Truth Will Prevail, London: Merlin Press.

Swain G and Swain N (1993) Eastern Europe since 1945. Basingstoke: Macmillan

Hot Pink Protest: Bulgarian Monument Repainted as ‘Artistic Apology’ for 1968 Czechoslovakian Invasion.

This week marked the 45th anniversary of ‘Operation Danube’, the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Overnight on 20-21 August 1968 a combined force of up to 200,000 Soviet, Bulgarian, East German, Hungarian and Polish troops entered and occupied Czechoslovakia to crush the political liberalisation sparked by communist leader Alexander Dubcek’s reformist ‘Prague Spring’ and implement a period of ‘normalisation’. You can read more about the failure of the Prague Spring and the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion in a previous blog post here.

Of course, the 45th anniversary of the invasion was commemorated in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In Prague, several top Czech officials (including current Prime Minister Jiří Rusnok, lower house speaker Miroslava Němcová and Prague Mayor Tomáš Hudeček) marked the occasion in a ceremony that took place outside the Czech Radio building that had formed one of the centres of resistance in 1968.

A prominent monument to the Soviet Army in Sofia was anonymously painted pink earlier this week as an ‘artistic apology’ for Bulgaria’s role in the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Photo Credit: Assen Genov, Facebook, via novinite.com: http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=153005

However, this year domestic remembrance was overshadowed by developments in Bulgaria, where anonymous artists spray painted a prominent monument to the Soviet Army pink with the accompanying slogan ‘Bulgaria Aplogises’ (written in both Czech and Bulgarian) indicating remorse for Bulgarian involvement in the invasion. Back in 1968 Bulgarian communist leader Todor Zhivkov was the leading advocate of hard-line intervention to quell Dubcek’s reforms, and critics have since pointed out that Bulgaria was the first Warsaw Pact country to insist on military intervention in 1968 and the last communist-bloc country to formally apologise for their involvement, in 1990. This week, a Bulgarian blogger interviewed one of the anonymous artists, who confirmed that choosing pink paint was a deliberate nod to Czech artist David Černý, who famously painted a Soviet tank dedicated to the memory of the 1945 liberation of Prague pink in 1991, an act which sparked controversy and ultimately led to the tank’s removal to a military museum.

Close-up of the Bulgarian memorial, which was painted to correspond with the 45th anniversary of ‘Operation Danube’ – the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Photo Credit: ArtDaily.Org http://artdaily.com/news/64528/Pink-makeover-for-Warsaw-Pact-invasion-of-Czechoslovakia-monument-in-Bulgaria-#.UheT6X_3PN6

Photos of the freshly re-painted monument quickly spread around the world via social networking sites and the story was also picked up by several international media organisations. The Bulgarian authorities moved quickly to try to ensure damage limitation: the monument was cleaned the following night (an operation allegedly conducted by volunteers from the ‘Forum Bulgaria-Russia’), while the Regional Prosecutor’s Office in Sofia swiftly announced the launch of pre-trial proceedings against the (still unknown) perpetrators on charges of ‘hooliganism’ which could result in a sentence of up to two years in jail if pursued, although this seems unlikely unless they are identified. However, Alexander Lukashevich, a spokesman from the Russian Foreign Affairs Ministry said that the Russian government intend to formally request that the Bulgarian authorities take action to punish those responsible and prevent the recurrence of any similar incidents in future. His statement demanded ‘the adoption of effective measures to prevent the mockery of the memory of the Soviet soldiers who died for the liberation of Europe from Nazism and Bulgaria, to identify and punish those responsible’.

This was not the first time that the Soviet Army monument in Sofia has been the subject of a controversial makeover. It has been subject to repeated graffiti, most famously in June 2011 when the statues were re-painted to resemble a collection of well-known Western pop culture heroes including Superman, The Joker, Captain America and Ronald McDonald, the flag held by the soldiers was painted with the US stars and stripes and an accompanying

The same monument was famously subjected to a superhero themed makeover in June 2011. Photo Credit: http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/2011/06/graffiti-artist-turns-bulgarian-war-memorial-into-superhero-monument/

slogan proclaimed that the makeover was ‘In Step With The Times’. I also wrote about this in an old blog post here. The Soviet monument has long divided opinion in Bulgaria – many view the statue as a symbol of communist repression, and there have been several calls for it to be destroyed, or at least moved from its current (prominent) location in central Sofia to the city’s museum of communism which opened in 2011. But these proposals are opposed by others who argue that the statue represents Bulgaria’s liberation from fascism in WWII and charge those who want the statue removed with ‘historical revisionism’. Of course, this debate is not just taking place within Bulgaria; over twenty years after the collapse of communism, the status of Soviet WWII memorials as symbols of liberation or oppression are still frequently contested throughout the former communist bloc. For more on this topic see my previous blog post here.

The latest ‘attack’ on the Soviet memorial in Sofia must also be understood in the context of growing domestic unrest in Bulgaria, where large-scale protests against the current government (which is dominated by the former communist party) have been occurring on a daily basis since June. Interestingly, photos of the on-going anti-government protests in Sofia following the controversial repainting of the memorial earlier this week show demonstrators brandishing a cardboard cut-out of Černý’s ‘pink tank’.

Anti-government protestors in Bulgaria this week holding a cardboard cut-out of David Cerny’s ‘pink tank’. Phto Credit: photo by journalist Nayo Titzin, Facebook via novinite.com http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=153077

However, the Czechs have also experienced a summer of political turmoil, triggered by the collapse of Petr Necas’s government following a corruption scandal in June. Czech MPs recently passed a vote of no-confidence, dissolving parliament and triggering an early election this autumn that threatens to return the communist party to power. Some Czech officials used the 45th anniversary of the Warsaw Pact invasion earlier this week, to warn against the return of the communists to political power, with Prague Mayor Tomáš Hudeček commenting that:

“This day is important for all of us because many people of my age and younger don’t know what the communist era was like. They don’t remember the shortages of oranges and bananas but also more important issues – the lack of freedom, the lack of responsibility for one’s actions, and so on. I believe that marking this anniversary will help us remember all these things of the past … Many things have not changed since the fall of communism in 1989. Changing people’s way of thinking is so much more difficult than changing the way the streets and cities look, for example”.

“Among all these crooks, I am the one to be here today!” – A Czechoslovakian Corruption Scandal.

Prior to the recent ‘student showcase’, my last blog post discussed the privileged position enjoyed by the political elite in communist Eastern Europe. This is a subject that relates to my own research into criminal networks during the communist era, as the desire for various luxury goods and services encouraged widespread corruption and the development of extensive illegal supply networks. I’ve recently been reading about one such illegal ‘supply chain’ established in Czechoslovakia and overseen by Stanislav Babinsky. In 1987, Babinsky, the manager of a catering and supply company who was locally known as the ‘King of Oravia’, was tried and convicted on charges including theft of socialist property worth $382,000 and the unlawful handling of state funds.

As corruption was so pervasive among the communist elite, high profile trials and convictions such as this were rare. On those occasions when high-ranking individuals were held to account for economic crimes, ‘justice’ tended to be politically motivated. Those unlucky enough to find themselves on the stand were generally targeted for one of three reasons: because they had fallen out of political favour (with corruption charges a useful way to remove someone from power); because they had lost their political protection, or because they were unlucky enough to be scapegoated for propaganda purposes, with convictions generally corresponding with the launch of a new ‘anti-corruption drive’. This was particularly true during the 1980s, following the launch of Soviet leader Yuri Andropov’s initial anti-corruption drive in 1982 and Mikhail Gorbachev’s later policies of encouraging perestroika and glasnost across the communist bloc, including well-publicised campaigns to ‘clean up’ corruption and economic crime. Even within the context of the changing political climate of the 1980s the Babinsky case is unusual, because of the high levels of media coverage it received. Developments were widely reported by both the Czechoslovakian media and in the international press, after a 15 page transcript of the trial was secretly smuggled out of the country.

The Babinsky trial was held at the Palace of Justice in Bratislava, where over the course of a three month period between 23 March and 30 June 1987, 800 witnesses were interrogated and 34,000 pages of documentary evidence were submitted. The trial involved a number of state officials who were accused of theft of state property, embezzlement, unlawful handling of state funds and gross negligence, to the cost of 2.2 million CZK.[i] Twelve individuals (all of whom held positions of varying political and economic importance) were formally charged and ten of these were convicted.[ii] However a much wider network of party and government officials were also implicated during the trial. High profile officials linked to the Babinsky scandal included Bohuslav Chnoupek, former foreign minister of Czechoslovakia; Peter Colotka, Slovak Prime Minister; Frantisek Miseje, Slovak Minister of Finance and General Kovak, head of Slovakian National Security – all of whom were named in testimony given during the trial.

Most of the attention at the trial centred around the testimony of chief defendant Stanislav Babninsky, the 59 year old director of Jednota, a state owned catering and supply business based in Dolny Kubin, a mountainous and predominantly agricultural region located about 120 miles north east of Bratislava. Known as ‘Kmotr’ (‘Godfather’) and nicknamed ‘The King of Oravia’ Babinsky had placed Jednota firmly at the heart of an extensive web of corruption and illegal trading, supplying money, luxury goods, services and entertainment to members of the political elite.[iii]

Stanislav Babinsky – photograph taken from http://www.dokweb.net/en/documentary-network/east-european-docs/-stanislav-babinsky-the-life-is-an-uncompromising-boomerang-5763/?off=3750

Evidence given at the trial revealed that between 1975 and his arrest in 1984, Babinsky had regularly supplied his various ‘connections’ with luxury items including ‘the best salami, smoked ham and whisky smuggled from Vienna and chocolates from Switzerland’.[iv] A second report detailed how:

“Babinsky and his accomplices delivered, free of charge, or at ridiculously low prices, consumer durables and fine foods to members of the political elite {including] … furniture (handmade and of special quality), artwork, watches, hunting rifles, a stereo system, gasoline vouchers, heating oil, electrical cable, beer, vodka, brandy and vast quantities of food, all from a special ‘diplomatic warehouse’”.[v]

Babinsky also detailed how he had organised construction of an elite holiday complex, Myln (‘The Mill’) in the nearby town of Brezovci, at a cost of nearly 4.5 million CZK, money which was all illegally sourced from state funds. Described as a ‘government rest home’ Myln was regularly used to host exclusive hunting parties, where guests could shoot at game from helicopters. Babinsky claimed that on one occasion 36,000 CZK had been spent on refreshments at a special bear shoot arranged for General Jan Kovac, Head of the Slovak Secret Police. Babinsky also revealed how he satisfied the seedier desires of his guests, who could ‘order’ prostitutes by calling the hotel reception and using the code word ‘Russian Reader’ – then, when asked if they required a particular volume, the numbers ordered would refer to the bust size favoured by the client! Babinsky claimed that Myln was the venue for wild sex parties and that ‘the immoralities that took place there made me want to throw up’, although he also claimed that the girls he employed were well treated, ‘rewarded handsomely [and] paid 1,500 koruny a night’, money that had been siphoned off from a fund designed to finance bonuses for ‘exceptional development of consumer cooperatives’ in the area.[vi]

Although Babinsky was referred to as a ‘power broker’ and a criminal ‘godfather’ by state media, during the trial he presented himself as victim rather than villain. Describing himself as ‘a man co-opted by the system to administer the ‘fringe benefits’ that those in power demanded’, Babinsky also perceived himself as a modern-day ‘Robin Hood’, insisting that he had never used his position for personal gain, but was motivated by the opportunity to secure higher levels of industrial investment and regional development from corrupt officials.[vii] He also claimed that he was merely a scapegoat for the crimes committed by those in power. Towards the end of the trial proceedings Babinsky openly wept, proclaiming ‘Among all these crooks, I am the one to be here today! And I had nothing out of it but hard work…’, and lamenting the fact that the crooked officials were the real criminals, for ‘enriching themselves at the expense of society’. Babinsky’s pleas were in vain however, and at the end of the trial he was sentenced to a total of 14.5 years imprisonment, along with nine other individuals.[viii]

So, what can the Babinsky case tell us? Firstly, the details which emerged during the trial testimony effectively demonstrate how deeply established corrupt networks had become by the final years of communism, illustrating the levels of privilege enjoyed by members of the political elite in Eastern Europe. Secondly, while the Babinsky case initially appeared to support enhanced efforts to reduce corruption in line with the changing political climate of the mid-1980s, its real impact was much more limited. True, Babinsky’s arrest came in the aftermath of Andropov’s anti-corruption drive, while his trial took place after Gorbachev’s reform programme had begun to influence the climate in Eastern Europe.[ix] When Milos Jakes took over the leadership from Gustav Husak in Czechoslovakia in 1987 he also declared that ‘corruption in official ranks must be combatted’.[x] However, in many respects the Babinsky case actually highlights the limits of any serious attempts to root out corruption among members of the communist elite. At the time, Der Spiegel called the Babinsky case ‘one of the biggest corruption scandals in the history of Czechoslovakia’ but the political impact of the case was negligible.[xi]

Babinsky was guilty of the charges against him, but he was also clearly a useful scapegoat. While he was publicly vilified and sentenced to 14.5 years in prison, the higher ranking beneficiaries of his illegal efforts escaped largely unscathed. The identities of the state officials incriminated in his testimony were omitted from the indictment on the direct orders of Slovak Justice Minister Pjescak, who had already prohibited any tape recording of the trial, as soon as it became clear that high ranking officials were going to be ‘named and shamed’ in court testimony! On 3 July 1987, following publication of the court verdict, the CPCZ CC Presidium published a statement in Rude Pravda announcing the expulsion of ‘those guilty parties connected with the Babinsky case’ from the communist party. However, only two district officials were actually named in this statement (Deputy Interior Minister Jan Kovac and former Central Committee Department head Stanislav Dudek) with vague references to the expulsions of ‘other (unnamed) members recently convicted of corruption’ and ‘reprimands ‘with warnings’ issued to five other anonymous state officials.[xii] The following day, Rude Pravda also carried a timely editorial criticising any ‘abuse of rank, position, bribery and nepotism’ and warning that in future any such activities would be exposed.[xiii] But these words were not supported by action: although a state committee was established to investigate Babinsky’s testimony, their closing report claimed that Babinsky had ‘cast unjustified aspersions on a number of innocent party members … a political provocation which the Western media had misused’, while a subsequent politburo statement also maintained that while a few guilty parties had been justly expelled, ‘other comrades named in the press had been falsely accused’.[xiv]

[i] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL Report SR/10, 10 August 1987; Mädchen nach Maß (‘Girl to Measure’), Der Spiegel, 26/1987 ‘Czech Aides Linked to Scandal’, The New York Times, 8 June 1987

[ii] ‘Premier Quits in Shake up of Czech Regime’, LA Times, 11 October 1988

[iii] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL, 10 August 1987; Mädchen nach Maß, Der Spiegel, 26/1987

[iv] Mädchen nach Maß, Der Spiegel, 26/1987

[v] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL, 10 August 1987

[vi] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL, 10 August 1987; Mädchen nach Maß, Der Spiegel, 26/1987

[vii] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL, 10 August 1987; Mädchen nach Maß, Der Spiegel, 26/1987; ‘Czech Aides Linked to Scandal’, The New York Times, 8 June 1987

[viii] Corruption Trial in Bratislava: Catering for the Elite’, RFE/RL, 10 August 1987

[ix] Other high profile ‘casualties’ of the anti-corruption drive in Eastern Europe include the conviction of Maciej Szcepanski, Central Committee member and head of the Polish committee for Radio and Television in 1984 on 35 counts of bribery and embezzlement and the conviction of Bulgarian Deputy Minister for Foreign Trade Georgi Vute in January 1987 for bribery and currency offences.

[x] ‘Officials Booted Out of Party’, Associated Press, 20 February 1988

[xi] Mädchen nach Maß, Der Spiegel, 26/1987

[xii] ‘Communist Party Expells District Officials’, Associated Press, 4 July 1987 and RFE/RL Weekly Record 18-24 February 1988 (OSA Archives, 26-2-1988)

[xiii] ‘Communist Party Expells District Officials’, Associated Press, 4 July 1987

[xiv] ‘Corruption Trial in Bratislava: The Party Metes Out Penalties’, RFE/RL 13, 1988; ‘Officials Booted Out of Party’, Associated Press, 20 February 1988

Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe

In this, the final post in this year’s student showcase, Christian Parker considers the slow but steady growth in dissent and organised opposition in Eastern Europe in the decades following the Prague Spring. While the majority of citizens adopted an attitude of outward conformity, a small but vocal minority bravely continued to speak out against various aspects of communist rule, even in the face of sustained state repression and persecution. The state authorities adopted a range of coercive means to contain and marginalise dissent and non-conformity in both the political and the cultural sphere, however ultimately they were unsuccessful in their attempts to quell opposition to communist rule.

Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe.

By Christian Parker

The failure of Alexander Dubcek’s attempt to develop ‘socialism with a human face’ and the forcible crushing of the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia in August 1968 was the catalyst for an ‘era of stagnation’ in Eastern Europe. In a speech made to the Polish Communist Party on 12th November 1968, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev justified the recent military intervention in Czechoslovakia and confirmed that any future attempts to deviate from the ‘common natural laws of socialist construction’ would be treated as a threat.[1] The message was clear: any significant reforms to the existing system would not be tolerated. As Tony Judt notes, this ‘Brezhnev Doctrine’ set new limits on manoeuvrability and freedom within the Eastern bloc, each state ‘had only limited sovereignty and any lapse in the Party’s monopoly of power might trigger military intervention’.[2] As long as the Soviets were prepared to maintain communism in Eastern Europe by force, any attempt at challenging the status quo appeared futile so most people adopted a policy of outward conformity and passive acceptance towards communism. However, dissent and non-conformity continued to exist in Eastern Europe, and the authorities employed extensive repression against dissidents, developing a range of coercive tactics to ensure dissent and opposition remained on the fringes of socialist society.

Charter 77 and the Birth of Organised Opposition

Perhaps the most important dissident movement to emerge in Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Prague Spring was the Charter 77 group. Charter 77 was initially formed in response to the arrest of a popular Czechoslovakian band ‘The Plastic People of the Universe’ for musical non-conformism and social subversion, after the band wrote to dissident playwright Vaclav Havel (previously famous for his 1975 Open Letter to Husak which protested the pervasive fear and ‘fraudulent social consciousness’ dominating life in Czechoslovakia after the Prague Spring), requesting his help to campaign for greater tolerance in both the political and cultural spheres.[3]

Charter 77 therefore sought to establish a ‘constructive dialogue’ with the communist party, aimed at securing a range of human rights and individual freedoms, including freedom from fear and freedom of expression which the movement demonstrated were ‘purely illusory’ in communist Czechoslovakia.[4] The movement gained further impetus from the fact that the Czechoslovakian government had recently signed the Helsinki Accords, promising to uphold ‘civil, political, economic, social, cultural…rights and freedoms’.[5]

Signatures for Charter 77 – calling on the Czechoslovakian communist party to uphold commitments to basic freedoms and human rights. Signatories were harrassed and persecuted in a variety of ways.

On its initial publication in January 1977, the Charter initially bore 243 signatures, including those of Vaclav Havel, Pavel Landovsky and Ludvik Vaculik. The state acted quickly in an attempt to prevent the campaign gaining momentum by arresting Havel, Landovsky and Vaculik whilst they were en route to the federal assembly, where they planned to deliver a copy of the Charter. The state’s retaliation to Charter 77 was wide and menacing; leading figures associated with the movement were arrested and imprisoned and signatories were targeted via a wide range of other means including arrest, intimidation, dismissal from work, denial of schooling for their children, suspension of driver’s licenses and the threat of forced exile and loss of citizenship – Geoffrey and Nigel Swain note that by the mid-1980s over 30 ‘Chartists’ had been deported, including Zdenek Mlynar, former secretary of the Czechoslovakian communist party.[6] Charter 77 backed the ‘Underground University’ (an informal institution that attempted to offer free, uncensored cultural education) but lecturers were frequently interrupted by policemen, and leading figures including philosopher Julius Tomin, were harassed and assaulted by ‘unknown thugs’. Attempts were also made to pressure workers into signing anti-Charter resolutions, though as the state representatives failed to give the workers a copy of the Charter so they could see what they were signing against, the majority refused.[7]

However, state attempts to ‘bury’ Charter 77 were largely unsuccessful. An ‘Anti-Charter Campaign’ publicised by state-run media actually helped to increase the document’s profile and despite sustained repression, by 1985 only 15 of the original signatories had removed their names. Jailing high profile Chartists proved counterproductive – John Lewis Gaddis even argues that, in the case of Vaclav Havel, it was his imprisonment 1979-1983 that gave him the ‘motive and the time to become the most influential chronicler of his generation’s disillusionment with communism’.[8] (For more on Vaclav Havel, see the previous blog post HERE). While Havel became a dominant figure, other Charter 77 dissidents also continued to undermine state authority, right up until the velvet revolution of 1989. In 1988, two leading Chartists, Rudolf Bereza and Tomas Hradilek, wrote to Soviet Premier Gorbachev demanding that anti-reformist central committee secretary Vasil Bilak be tried for high treason due to his role in the invasion of Prague in 1968. Bilak was subsequently forced into retirement from politics. Tony Judt has suggested that by ‘moralizing shamelessly in public’ Havel and the other chartists created ‘a virtual public space’ to replace the one removed by communism.[9]

Vaclav Havel, speaking at home in May 1978. A leading figure in the Czechoslovakian dissident movement, Havel was subjected to intense surveillance, restricted movments, frequent arrest, interrogation and imprisonment.

The Wider Impact of Charter 77

Charter 77 also gave impetus to dissidents elsewhere in Eastern Europe and by 1987 their manifesto supporting the establishment of human rights across Eastern Europe had gained 1,300 signatures. Immediately after the publication of Charter 77 Romanian writer Paul Goma wrote an open letter of support and solidarity which was broadcast on Radio Free Europe. Goma also wrote to Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu, asking him to sign the letter! Goma’s publication gained just over 200 signatories for the Charter, however he faced a sustained campaign of repression and intimidation as a result. The street where he lived was cordoned-off, his apartment was repeatedly broken into and his phone line was cut. Several of his fellow signatories, including worker Vasile Paraschiv, were arrested by the Securitate and beaten when visiting Goma’s apartment. After Nicolae Ceausescu made a speech on February 17 denouncing ‘traitors of the country’, Goma sent him a second letter, describing the Securitate as the real ‘traitors and enemies of Romania’. Goma was expelled from the Romanian Writers Union and arrested – his release was secured following an international outcry but after continued harassment Goma immigrated to Paris on November 20, 1977. Even this didn’t stop Romanian attempts to silence Goma, and the Securitate made two attempts to silence him permanently while he was living in Paris – sending him a parcel bomb in February 1981 and attempting to assassinate him with a poisoned dart on January 13, 1982.[10]

Paul Goma’s case was not an isolated incident – while attempted assassinations abroad were rare, this tactic was occasionally used to silence particularly troublesome East European dissidents. For example, writer and broadcaster Georgi Markov’s defection to London from Bulgaria led to him being declared a persona non grata, and he was issued a six year prison sentence in absentia. He continued speaking about against the communist regime in Bulgaria on the BBC World Service and Radio Free Europe, and on 7th September 1978 a Bulgarian Security Agent fired a poisoned ricin pellet into Markov’s leg while he was waiting at a bus stop in central London. He died a few days later (For more on the Georgi Markov assassination see the previous blog post HERE).

Dissent and Non-Conformity in the GDR

In many respects, dissent in the GDR was the result of unique conditions within the communist bloc: it was arguably the only state which, even in the wake of the failed Prague Spring, could still boast an ‘informal and even intra-Party Marxist opposition’, a class of intellectuals who attacked the regime from the political ‘left’.[11] Thus, Wolfgang Harich desired a reunified Germany and wrote about a ‘third-way’ between Stalinism and Capitalism, another variant of ‘socialism with a human face’. Harich was particularly critical of the regime’s ‘bureaucratic deviation’ and ‘illusions of consumerism’ and similarly Robert Havemann and Wolf Biermann attacked the regime for supporting mass consumption and privately owned consumer goods. Rudolf Bahro, another leading East German dissident, is best known for his essay The Alternative, which Judt describes as ‘an explicitly Marxist critique of real existing socialism’.[12]

State leaders would not tolerate these revisionists, despite their Marxist leanings and the feared East German Stasi employed a range of methods to silence them. Mary Fulbrook notes that isolating dissident intellectuals was done ‘with relative ease by the regime’.[13] Thus Harich was imprisoned, Havemann was placed under house arrest and Bierman and Bahro were both forced into exile in the West. The case of Bahro provides a particularly disturbing insight into the lengths the Stasi were prepared go to. Bahro, dissident writer Jürgen Fuchs and outlawed Klaus Renft Combo band member Gerulf Pannach had all been held in Stasi prisons at a similar time and all later died from an unusual form of cancer. After the collapse of communism an investigation discovered that that Stasi had been using radiation to ‘tag’ dissidents. One of Bahro’s manuscripts was also discovered to have been irradiated so it could be tracked across to the west.[14]

The pervasive influence of the Stasi meant that any criticism of the East German regime, however mild, could have severe repercussions. Erwin Malinowski, who wrote a letter of protest about the treatment of his son, who was imprisoned after applying to move to West Germany in January 1983, was placed in a Stasi remand prison for seven months and then served two years further imprisonment for ‘anti-state agitation’. His son was eventually ‘bought free’ by the West Germans, one of the measures through which dissenters could escape the GDR. West German money also secured the release of Josef Kniefel who in March 1980 attempted to blow up the Soviet tank monument in Karl-Marx-Stadt in protest over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan the previous December. He had previously served a ten month prison sentence for attacking Stalin’s crimes against humanity and the role of the ruling parties of Eastern Europe.[15] For other dissidents, ‘repressive tolerance’ and limited publishing space proved effective measures by which the GDR could assert control. The GDR’s response to dissent was effective, however despite the relative success of the Stasi in isolating prominent dissident intellectuals, the regime never achieved total success in quelling dissent, discontent, or opposition.[16]

During the 1970s and 1989s, the peace movement, environmental movement and Protestant Church also provided citizens with outlets to vent their frustrations. Many who joined these organisations sought to improve the regime from within, disillusioned with the lack of respect for the environment and public health encouraged by growing industrialisation and the use of nuclear energy, something which was exacerbated by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986. To control environmental dissidents, the state banned the publication of data relating to the environmental situation in the GDR. Moreover, Stasi attempts to infiltrate and break up these groups met some success. For example, the main Church environmental movement Kirchliche Forschungsheim Wittenburg was infiltrated by the Stasi to the point where it lost its relevance in the wider environmental movement. However, the organisational networks, political strategies and the experience built up during the 1980s, set the stage for these groups to later serve as a vital part of the revolution of 1989. Such vociferous opposition thus taught East German dissidents the ‘complex arts of self-organization and political pressure group work under dictatorial conditions’[17]

The GDR not only took a hard line against intellectual dissent but also persecuted cultural non-conformity. For example, the Klaus Renft Combo, described by Funder as ‘the wildest and most popular rock band in the GDR’, agitated the state so much that at the bands attendance at the yearly performance licensing committee meeting in 1975 they were informed that ‘as a combo … [they] no longer existed’. Copies of their records disappeared from the shelves, and the radio stations were prohibited from playing their songs. Klaus Renft was exiled west, and several other band members were imprisoned. Despite this, the GDR failed to stop the band altogether, and they gained something of a cult following because of their repression by the state.[18] Attempts by the GDR and other East European regimes to prevent their citizens’ exposure to ‘Western culture’ were ultimately unsuccessful however, with bootleg records and cassette tapes smuggled in and distributed on the black market and the increased availability of television sets and video recorders in the 1980s allowing citizens access to Hollywood films and TV series such as ‘Dallas’. (For more information about the impact of popular culture on communist Eastern Europe see the previous blog posts ‘Video May Have Killed the Radio Star, But Did Popular Culture Kill Communism?’ HERE and ‘Rocking the Wall’ HERE).

The Klaus Renft Combo – In 1975 the band were targeted due to their ‘subversive lyrics’ and were forcibly disbanded. Members were arrested and forced to leave the GDR for West Germany.

Conclusion

It is clear that the regimes of Eastern Europe possessed a vast array of techniques with which they attempted to silence those who attempted to oppose or criticise communism. These dissidents could not directly bring down the regimes they spoke out against; partly due to the success of state attempts to contain, control them and limit their influence, and partly because they lacked sufficient popular mandate amongst their populations. Certainly though, through their bravery and continued campaigns in the face of persecution and oppression they created hope, and in many ways they helped to set the precedent for the revolutionaries of 1989.

About the Author

Christian Parker has just completed his BA (Hons) in History at Swansea University. In his final year of study, Christian specialised in East European History. After taking the next year off to travel, Christian hopes to begin postgraduate study in 2013.

[1] The Brezhnev Doctrine (12 November 1968) available online @ http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1968brezhnev.asp

[2] Tony Judt, PostWar (Plimlico, 2007), 446

[3] Dear Dr. Husak (April 1975) – available online @ http://vaclavhavel.cz/showtrans.php?cat=eseje&val=1_aj_eseje.html&typ=HTML

[4] Declaration of Charter 77, published in January 1977, available online @ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/czechoslovakia/cs_appnd.html

[5] Helsinki Accords (1 August 1975) – excerpt available online @ http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/245

[6] Geoffrey Swain and Nigel Swain, Eastern Europe Since 1945 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 185

[7] Sabrina Ramet, Social Currents in Eastern Europe, (Duke University Press, 1995), 126

[8] John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, (Penguin 2007), 191

[9] Tony Judt, PostWar (Plimlico, 2007), 577

[10] Dennis Deletant, Ceausescu and the Securitate, Coercion and Dissent in Romania, 1965-1989, (Hurst & Co., 1995), 235-242

[11] Tony Judt, Post War, (Plimlico, 2007), 573; Christian Joppke, ‘Intellectuals, Nationalism and the Exit From Communism: The Case of East Germany’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 37, 2 (April 1975), 216.

[12] David Childs and Richard Popplewell, The Stasi, The East German Intelligence and Security Service, (Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996), 99; Tony Judt, Post War, (Plimlico, 2007), 573-574.

[13] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995), 176.

[14] Anna Funder, Stasiland, (Granta Books, 2004), 191

[15] David Childs and Richard Popplewell, The Stasi, The East German Intelligence and Security Service, (London: Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996), 97-98

[16] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995) 201.

[17] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995)

[18] Anna Funder, Stasiland, (Granta Books, 2004), 185-191

Dubcek’s Failings? The 1968 Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Continuing the theme of protest and rebellion, this article considers ‘Operation Danube’, the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Here, Rebekah Young discusses the failure of Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubcek’s attempt to create ‘socialism with a human face’ and explores the complex decision-making process, mistakes and miscalculations that resulted in military intervention in August 1968.

Dubcek’s Failings? The 1968 Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia

By Rebekah Young.

During the night of August 20-21, 1968, the joint forces of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia. This was the biggest military operation in Europe since the Second World War as up to 200,000 troops from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary occupied Czechoslovakia in ‘Operation Danube’. Launched in response to the reform movement led by Czechoslovakia leader Alexander Dubcek (known as the ‘Prague Spring’), the Warsaw Pact invasion was preceded by several months of negotiation and preparation. As Jiri Valenta argues, the Soviet leadership decided to intervene in Czechoslovakia ‘only after a long period of hesitation and vacillation’.[1] During the course of 1968, the steady escalation of Dubcek’s reform programme first disquieted and then alarmed Moscow, finally persuading Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev that Soviet interests were seriously compromised by the threat of ‘counter-revolution’ in Czechoslovakia. In particular, Dubcek’s failure to respond to numerous warnings and ultimatums issued between April and August 1968 seems to have played a vital role in influencing Brezhnev’s decision to sanction military intervention.

Alexander Dubcek and ‘Socialism with a Human Face’.

Alexander Dubcek became leader of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party on 5 January 1968. When he assumed the leadership, Dubcek faced the challenge of revitalising the public standing of the Communist Party; the previous leader Antonin Novotny had been widely criticised for his inability to redress the ‘political discontent of the people’ and the ‘declining activity and interest’ of communist party members. On 5 April 1968 Dubcek published his Action Programme, a series of proposed reforms which aimed at improving economic conditions in Czechoslovakia and sanctioned a higher degree of liberalisation, promising greater freedom of speech, movement, association and greater political participation by non-communist organisations. The power of the police, military and judiciary were also to be curtailed.

Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubcek – his attempt to create ‘socialism with a human face’ sparked the 1968 Prague Spring.

Dubcek’s Action Programme was an experiment in reform from above. It was Dubcek’s intention that the Communist Party would retain its ‘leading role’ in Czechoslovakia, but he hoped that by encouraging a more open exchange of views and a higher level of political participation, he could narrow the gap between the Party and society, revitalising communism and enabling the party to gain greater legitimacy and public support, thus creating ‘socialism with a human face’.[2] The Action Programme was hardly a revolutionary document; it intended to strengthen state socialism and posed no fundamental challenge to the Soviet Union and its satellite states. While Dubcek aimed to redefine the role of the communist party, he did not seek to abandon it. In particular, the programme emphasised orthodoxy in foreign policy, stressing a continued commitment to ‘fighting the forces of imperialist reaction’ and stating that ‘the basic orientation of Czechoslovak foreign policy ….revolves around alliance and cooperation with the Soviet Union and the other socialist states’. Throughout 1968, Dubcek continued to emphasise that Czechoslovakian commitments to the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries would not change.[3]

However, Dubcek’s proposals had the potential for considerable movement away from the orthodox Soviet model, diluting the ‘leading role’ of the communist party in state and society. Jiri Valenta even refered to the Action Programme as the ‘Magna Carta of Dubcek’s new leadership’.[4] The Action Programme thus sparked Soviet concerns, as Moscow began to monitor developments in Czechoslovakia carefully.

The Prague Spring: April-August 1968

Developments in Czechoslovakia between April-August 1968 led to rising alarm in the Soviet Union and elsewhere in the East European bloc. On 4th May Dubcek visited Moscow, where certain aspects of his Action Programme were criticised and he was cautioned by Brezhnev to ensure that any reforms remained ‘within acceptable bounds’.

The abolition of censorship in Czechoslovakia, allowed a level of freedom of speech unheard of elsewhere in the communist bloc. This was a matter of great concern for the Soviets. Dubcek’s decision to encourage political debate opened the floodgates of free expression and inevitably led to criticism of the Communist Party’s monopoly of power and past brutality. This is perhaps best illustrated by Ludvik Vaculik’s ‘Two Thousand Words’, which was published in June 1968. The article supported Dubcek and the continued role of the communists in leading a ‘democratic revival’ in Czecholsovakia and rejected the use of ‘improper or illegal methods’ against the Party. However, Vaculik was extremely critical of the Party’s past record, criticising high levels of repression, stating that the Party had gone from ‘a political party and ideological grouping into a power organisation’ led by ‘power-hungry egoists, reproachful cowards and people with bad consciences’. Vaculik believed the government had ‘forgotten how to govern’ and called for the resignation of those who had previously misused their power.[5]

Vaculik’s plea inspired widespread support in Czechoslovakia and sparked serious concern from the Soviets. The Two Thousand Words hinted at the potential for action from below that could destroy the leading role of the party and the Soviet leadership condemned the article as ‘an anti-socialist call to revolution’.[6] This was one of the catalysts for convening a Warsaw Pact meeting in July, which Navratil believes ‘marked the point of no return for Soviet policy on rolling back the Prague Spring’.[7]

The Soviets were also increasingly concerned about Dubcek’s apparent willingness to dilute the leading role of the communist party with moves towards political pluralism; proposals to increase the involvement of non-communist organisations within the political sphere and plans to vote on further political ‘restructuring’ at the 14th Czechoslovakian Party Congress at the end of August. Galia Golan believes that the increasingly politicised nature of Dubcek’s reforms was a crucial factor, arguing that, ‘it was the democratic nature and content of the Czechosovak experiment … which precipitated the invasion’.[8]

Perhaps most importantly, the Prague Spring posed a wider security issue, with fear of demands for reform triggering a ‘domino effect’ elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Other East European leaders began to press Brezhnev for a hard-line intervention in Czechoslovakia to minimise any damage to their own country. In particular, the Ukrainian, Polish and East German leaderships began complaining about the danger of ‘contamination’. In Ukraine, people began to openly voice their long standing discontent with Soviet domination and express solidarity with Dubcek and the Czechoslovakian people. Polish leader Gomulka was particularly angered by public criticism in Prague about Polish anti-Semitism, while East German leader Ulbricht strongly opposed any suggestion that the Czechoslovakian Communist Party might give up its monopoly of power.[9] Minutes from a secret meeting of the ‘Warsaw Five’ in Moscow on 8 May 1968 demonstrate that Gomulka and Ulbricht took the most hard line stance, repeatedly insisting that a ‘counterrevolution’ was underway in Czechoslovakia and emphasising the need for outside military intervention.[10] However, Brezhnev remained reluctant to send tanks into Czechoslovakia, hoping to coerce Dubek to keep his reforms within ‘acceptable limits’ instead.

Moscow’s Warnings: Mistakes and Miscalculations

When the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Dubcek expressed complete shock at this ‘unexpected’ turn of events, declaring ‘On my honour as a communist, I declare that I did not have the slightest idea … that anyone proposed taking such measures against us’.[11] However, the available evidence indicates that Soviet pressure on Dubcek to reverse his reform programme intensified between April and August 1968 and that Brezhnev repeatedly warned Dubcek about the possibility of outside intervention if he did not act decisively to bring the Prague Spring back under control. Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the Prague Spring was Dubcek’s failure to heed Brezhnev’s warnings. Instead, he remained seemingly oblivious to the increasingly dangerous position he was in, despite the precedent set by the earlier Soviet invasion of Hungary to prevent escalating reform in 1956, with Hungarian leader Kadar knowingly warning Dubcek ‘Do you really not know the kind of people you are dealing with?’[12] (For more on the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary see the previous blog post HERE)

‘Fraternal Cooperation’ – Dubcek and Brezhnev embrace. However, relations between the two deteriorated as Brezhnev became increasingly frustrated by Dubcek’s unwillingness to bow to Soviet pressure and halt his reform programme.

A series of meetings held during the summer of 1968 illustrate a slow but steady course towards military intervention. On 14-15 July an emergency meeting to discuss the situation in Czechoslovakia resulted in a letter claiming that ‘hostile forces’ in Czechoslovakia posed a serious threat and emphasising the ‘solidarity and general assistance of fraternal socialist countries to defend Czechoslovakia and uphold the socialist system’.[13] The letter was sent to Dubcek (who had been absent from the meeting) but he dismissed these criticisms. Between 29 July and 1 August a further series of meetings were held between the Czechoslovak and Soviet leaderships at Cierna nad Tisou, where Dubcek bowed to sustained pressure and promised a series of concessions including a halt to political reform and the re-imposition of a higher level of censorship. However, after the summit Dubcek ‘continued his course as if nothing had happened’, despite dispatches from the Czechoslovak Ambassadors in Berlin, Warsaw and Budapest reporting on a ‘steady military build-up’ under way in the Eastern bloc.[14] Cierna nad Tisou can be seen as a crucial tipping point: had Dubcek acted decisively to regain control over the reform process after the meeting, invasion may have been avoided. Tigrid believes this was a ‘tragic misunderstanding’ on Dubcek’s part, while a CIA Intelligence Memorandum dated 21st August 1968 observed that ‘Cierna proved only that the Czechs had not understood … that they should put their reform movement into reverse.[15]

On 3 August the Bratislava Declaration further emphasised Warsaw Pact commitment to ‘strengthening and developing fraternal cooperation among the socialist states’, and vigilance against any attempts to weaken the leading role of the communist party.[16] The stage was set for intervention. Records of two telephone conversations between Brezhnev and Dubcek on the 9 and 13 August mark the final point of no return for Moscow. An increasingly frustrated Brezhnev explained to Dubcek that the situation was now ‘very serious’; accusing him of failing to adhere to the agreements reached in Cierna and Bratislava; rebuking him for his lack of action and ‘deceit’ and stating that ‘independent measures’ would be employed to defend socialism. Dubcek merely requested more time, arguing that rapid changes to restore domestic order were impossible during such a complex process.[17]

Conclusion

On August 17th, the final decision to launch Operation Danube was made. This came after much deliberation between Brezhnev and the other Warsaw Pact members. The invasion was the result of a fragile balance of conflicting ideas. By August 1968 Dubcek’s failure to slow the pace of reform in Czechoslovakia convinced Brezhnev that some form of intervention was required.[18]While Brezhnev was initially reluctant to send troops in to Czechoslovakia Dubcek’s seeming refusal to limit his reform programme despite repeated warnings and ultimatums, coupled with pressure from other East European leaders left little choice but to take decisive action. Dubcek had clearly underestimated the warnings of the Warsaw five, who believed that he had lost control over the Prague Spring. He failed to convince them that he had the power and initiative to prevent a counter-revolution and was ultimately considered too ‘unreliable’ to maintain socialism in Czechoslovakia.

VIDEO: Soldiers and Eyewitnesses remember the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia:

About the Author: