CFP: Exploring Experiences of Repression in the Soviet Union and Communist Eastern Europe (Leeds, January 2017)

CALL FOR PAPERS

EXPLORING EXPERIENCES OF REPRESSION IN THE SOVIET UNION AND COMMUNIST EASTERN EUROPE.

DATE: Friday 20th January 2017

VENUE: Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK.

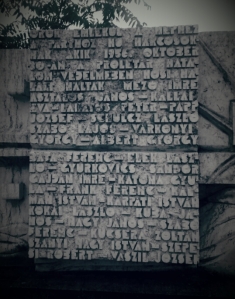

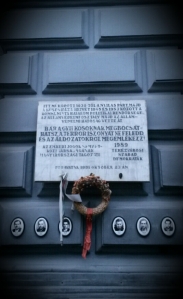

Memorial to the Victims of Communism (Prague, Czech Republic)

SUMMARY

In recent years there has been renewed academic interest in studying experiences of repression in the former communist bloc as scholars increasingly recognise the need to move beyond previously narrow definitions of communist ‘terror’ and ‘repression’ to reflect better its multifaceted political, ideological and socio-economic dimensions. Today, while we know more about the politics of the purges, we know significantly less about the impact of the repressions as an everyday experience. In addition to continued focus on directly enforced aspects of state repression (including arrests, executions, non-judicial murders, show trials, mass deportations and incarceration in penal institutes and forced labour camps), recent studies have emphasised the impact of practices such as more general police surveillance, enforced conscription, confiscation of property, eviction from dwellings, loss of employment and social status.

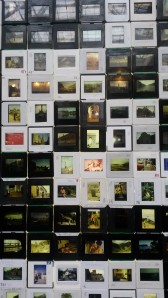

Since 1989, with the collapse of the socialist regimes in Eastern Europe, and 1991, with the collapse of the communist regime in the Soviet Union, a good deal of new material has become available about the repressive nature of these regimes and the impact this had on those who suffered under them. Today, historians have access to a wider range of source materials including recently released archival documentation, contemporary and historical newspaper reports, autobiographies/biographies, published testimonies of survivors and their family members, photographs and film. There has also been increased emphasis on oral history, due to concerted efforts to record individual experiences of repression, as many of those who experienced communist-era repression are nearing the ends of their lives.

If you would like to participate then please send proposals consisting of paper title, a brief (250 words) abstract and presenter’s details to Dr. Kelly Hignett at K.L.Hignett@Leedsbeckett.ac.uk by Monday 19th December.

Women and Repression in Communist Czechoslovakia

Today’s blog post, written for International Women’s Day 2016, relates to my current research into women’s experiences of repression in communist Eastern Europe, with a particular focus on Czechoslovakia 1948-1968, during the period of Stalinist terror and its immediate aftermath.

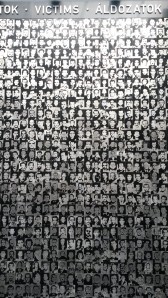

The vast majority of the 90,000 – 100,000 Czechoslovak citizens who were prosecuted and interned for political crimes between 1948-1954 were men; only between 5,000 – 9,000 (5-10%) were women. These women were held in numerous different prisons and forced labour camps across Czechoslovakia, where they frequently experienced poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene and medical care and enforced labour, while enduring physical and psychological violence, abuse and humiliation at the hands of the penal authorities. Beyond this, however, hundreds of thousands of other Czechoslovakian women also became ‘collateral’ victims of state-sanctioned repression during these years. The Czechoslovakian Communist Party actively pursued a policy of ‘punishment through kinship ties’, so while family members of those incarcerated for political crimes were not necessarily arrested themselves, they were considered ‘guilty by association’. As men comprised the majority of political prisoners, it was usually the women who were left trying to hold their families together and survive in the face of sustained political and socio-economic discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

The growth in published memoirs and oral history projects such as Paměť Národa and Političtívězni.cz in post-communist Czech Republic and Slovakia have encouraged more victims of repression to record their stories. However, women’s experiences of political repression in communist Czechoslovakia remain under-researched and under-represented in the historiography. It is often suggested that women are generally more reluctant to share personal accounts of traumatic experiences, in comparison with their male counterparts. For example Historian Tomáš Bursík’s study of Czechoslovakian women prisoners Ztratili jsme mnoho casu … Ale ne sebe! notes that in many cases ‘Women do not like to return to their suffering, that misfortune they affected, the humiliation that followed. They do not want to talk about it’. In her own account of imprisonment in communist Czechoslovakia, Krásná němá paní, Božena Kuklová-Jíšová also explained that:

‘We women are very often criticized for not writing about ourselves, about our fate. Perhaps it is because there were some moments which were very humiliating for us; or because in comparison to the many different brave acts of men, our acts seem so narrow-minded. But the main reason is that we have difficulties presenting ourselves to the world’.

This reticence extends to many women who experienced collateral or secondary repression, such as Jo Langer, who despite being subjected to sustained political harassment and socio-economic discrimination including loss of employment and forced relocation when her husband Oscar was arrested and interned 1951-1960, described how, upon receiving the first full account of her husband’s traumatic experiences in the camps after his release, she felt ‘shattered and deeply ashamed of having thought myself a victim of suffering’ (You can read more about Jo Langer’s autobiography Convictions: My Life with a Good Communist in my previous blog post HERE)

However, the inclusion of women’s narratives make an important contribution to the historiography, broadening and deepening our understanding of terror and repression in communist Eastern Europe. A number of women who endured political repression have shared their stories, which not only document their suffering at the hands of the Communist Party but are also testimony to their strength, resistance and will to survive. Through their narratives, these women are able to present themselves simultaneously as both victims and survivors of communist repression.

Today then, it seems fitting to mark International Women’s Day 2016 by briefly highlighting two examples to pay tribute to the many strong, spirited and inspiring women who feature in my own research.

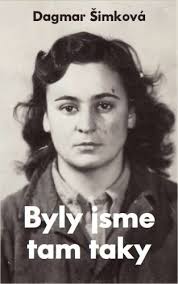

Dagmar Šimková

“The screeching seagulls are flying around me. I am so free, I can walk barefoot. And the waves wash away traces of my steps long before a print could be left”.

Dagmar Simkova’s arrest, official photograph (1952). Source: http://zpravy.idnes.cz/autorka-svedectvi-o-zenskych-veznicich-krasna-a-inteligentni-dagmar-simkova-by-se-dozila-80-let-i1u-/zpr_archiv.aspx?c=A090522_114346_kavarna_bos

Dagmar Šimková’s autobiographical account of her experiences in prison Byly jsme tam taky [We were there too] is arguably one of the strongest testimonies of communist-era imprisonment to emerge from the former east bloc. Šimková’s family became targets after the communist coup of 1948 due to their ‘bourgeois origins’ (her father had been a banker). Their villa was confiscated by the Communists, while Dagmar and her sister Marta were denied access to university. While Marta fled Czechoslovakia in 1950, Dagmar became involved in resistance activities, printing and distributing anti-communist leaflets and posters mocking the new Czechoslovakian leader, Klement Gottwald. In October 1952, following a failed attempt to help two friends avoid military service by escaping to the West, she was arrested, aged 23, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Between 1952 – 1966 Šimková passed through various prisons and labour camps in Czechoslovakia: in Prague, Pisek, Ceske Budejovice and Opava. In 1955 she even briefly escaped from Želiezovce, a notoriously harsh agricultural labour camp in Slovakia. Sadly, her freedom was shortlived: she was found sleeping in a haystack at a nearby farm two days later, recaptured and returned to Želiezovce, where an additional three years was added to her existing prison term as a punishment.

Dagmar Simkova’s book Byly Jsme Tam Taky [“We Were There Too”]

From 1953, Šimková was held in Pardubice Prison near Prague, in the women’s department ‘Hrad’ (Castle), which was specially created to house 64 women who were perceived as being the ‘most dangerous’ political prisoners, and segregate them from the main prison population. Here, Šimková participated in several organised hunger strikes to demand better conditions for women prisoners. She was also an active participant in the ‘prison university’ founded by former university professor Růžena Vacková, who gave secret lectures on fine art, literature and languages to her fellow prisoners. Šimková later described how ‘We devoured every word. We tried to remember, and understand, like the best students at universities’. Some of the women even managed to compile some lecture notes into a small book which was secretly hidden, before being smuggled out of Pardubice in 1965. This book is currently held in the Charles University archives.

After a total of fourteen years incarceration, Dagmar Šimková was finally released in April 1966, aged 37. Two years later, during the liberalisation of the Prague Spring in 1968 she was instrumental in establishing K 231, the first organisation to represent former political prisoners in Czechoslovakia. Following the Soviet invasion to halt the Czechoslovak reforms, Šimková emigrated to start a new life in Austrialia, where she completed two University degrees, worked as an artist, prison therapist and even trained as a stuntwoman! She also worked with Amnesty International , continuing to campaign for better prison conditions until her death in 1995.

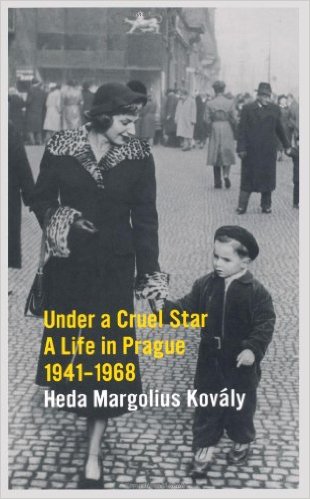

Heda Margolius Kovály

Heda Margolius Kovaly. Source: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/dec/13/heda-margolius-kovaly

Heda Margolius Kovály’s memoir, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 remains one of the most damning accounts of the violence and repression that characterised mid-twentieth century central and eastern Europe. Heda’s incredible life story spans the Nazi concentration camps, the devastation of WWII, the communist coup and the post-war Stalinist terror in Czechsolovakia. Having survived Auschwitz, Heda escaped during a death march to Bergen-Belsen and managed to make her way home to Prague. After the war, she was reunited with her husband Rudolf Margolius, who was also a concentration camp survivor, and a committed communist. Following the Communist coup of February 1948, Rudolf served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, only to quickly fall victim to the Stalinist purges. Rudolf was arrested on 10 January 1952, brutally interrogated and forced to falsely confess to a range of ‘crimes’ including sabotage, espionage and treason. He was subsequently convicted as a member of the alleged ‘anti-state conspiracy’ group led by former General Secretary, Rudolf Slansky, in Czechoslovakia’s most infamous show trial. In December 1952, Rudolf was executed, along with 10 of his co-defendents.

Following Rudolf’s arrest, Heda described how ‘Suddenly, the world tilted and I felt myself falling … into a bottomless space’ . She was left to raise their young son, Ivan, while fighting to survive in the face of sustained state-sanctioned repression. She was swiftly fired from her job at a publishing house, and was forced to work extremely long hours for pitifully little pay, while living on ‘bread and milk’ in order to make enough to cover their basic needs. Her savings and most of her possessions were confiscated, and she and Ivan were forced to leave their home and move to a single room in a dirty and dilapidated apartment block on the outskirts of Prague, where it was so cold that ice formed inside during the winter months, and cockroaches ‘almost as large as mice’ crawled up the walls. Abandoned by most of her former friends, Heda describes how she became a social pariah who was treated ‘like a leper’. At best, former friends and acquaintances would ignore her when they passed in the street, while others would ‘stop and stare with venom’ sometimes even spitting at her as she walked by.

The strain of living under these conditions caused Heda to become critically ill, but she was initially denied medical treatment. When she was finally admitted to hospital she had a temperature of 104 and a long list of ailments, leading the doctor who treated her to compare her to a newly released concentration camp survivor. It was while she was recovering in hospital that she heard Rudolf’s trial testimony broadcast on the radio, and she listened to her husband monotonously admit to ‘lie after lie’ as he recited the script he had been forced to learn. Forcibly discharged from hospital before she was fully recovered, Heda was so weak that she had to crawl ‘inch by inch’ from the front door of her apartment block to her bedroom, where she spent several weeks following Rudolf’s execution ‘motionless, without a thought, without pain, in total emptiness … lying in my bed as if it were a coffin’.

‘Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968’ is Heda Margolius Kovaly’s account of surviving Nazi and Communist persecution.

Nevertheless, Heda regained her strength. Her son Ivan later described how, even in the face of sustained persecution ‘Heda survived through her determination and managed to look after us both’. She continued to maintain Rudolf’s innocence and fought to clear his name, writing endless letters and attempting to arrange meetings with various communist officials, most of whom refused to see her. Following Rudolf’s execution, she dared to publicly mourn him by dressing completely in black, in a deliberate challenge to the Communist Party. After she remarried in 1955, she continued to campaign for Rudolf’s full rehabilitation. In April 1963, she was finally summoned to the Central Committee where Rudolf’s innocence was privately confirmed, and Heda was asked to write a ‘summary of losses’ suffered as a result of his arrest and conviction, so that she could apply for compensation. In Under a Cruel Star, she described how:

‘I sat down at my typewriter and typed up a list:

– Loss of Father

– Loss of Husband

– Loss of Honour

– Loss of Health

– Loss of Employment and Opportunity to Complete Education

– Loss of Faith in the Party and JusticeOnly at the end did I write:

– Loss of Property’.

Upon presentation of this list, the Communist officials responded in confusion:

‘”But you must understand that no one can make these losses up to you?”. “Exactly” I said “That’s why I wrote them up for you, So that you know that whatever you do you can never undo what you have done … you murdered my husband. You threw me out of every job I had. You had me thrown out of a hospital! You threw us out of our apartment and into a hovel where only by some miracle we did not die. You ruined my son’s childhood! And now you think you can compensate for that with a few crowns? Buy me off? Keep me quiet?”.’

Following the failed Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Heda left Czechoslovakia and settled in the USA with her second husband, Pavel Kovály. There, she continued to forge a successful career as a translator in addition to working as a librarian in the international law library at Harvard University. Heda Margolius Kovály died in 2010, aged 91. In addition to her personal memoir Under A Cruel Star, an English-language translation of Heda’s novel Nevina [Innocence] was recently published in 2015 – which I can also highly recommend!

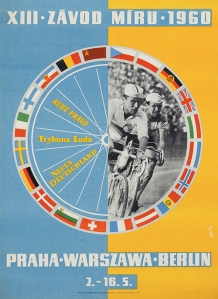

The Evolution of the Polish Solidarity Movement

THE EVOLUTION OF THE POLISH SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT – BY KIERAN INGLETON.

The Solidarity movement in Poland is arguably one of the most unique and inspiring movements in modern European history. Between 1980-1989, Solidarity led what has often been described as a “10 year revolution”, which ultimately resulted in the collapse of communism in Poland, a key turning point which triggered wider reform and revolution across the Eastern bloc. During this turbulent decade, Solidarity evolved from a legal trade union into an underground social network and protest movement, ultimately emerging as a revolutionary force, capable of toppling and replacing the communist system in Poland. (Bloom, 2013, pp374-375). Mark Kramer has argued that while Solidarity may have started out as a free trade union, it “quickly became far more: a social movement, a symbol of hope and an embodiment of the struggle against communism and Soviet domination” (Kramer, 2011).

THE BIRTH OF SOLIDARITY

The Solidarity movement emerged out of a much longer history of worker discontent, strikes and protest that had characterised tensions between the state and society in communist Poland since the end of WWII. Touraine has argued that “Solidarity first emerged because it was a response to Poland’s decline economically and socially. Nowhere else in Communist Central Europe was the failure of the governments industrial and agricultural policies so obvious” (Touraine, 1983, p32). From the mid-1970s, the Polish economy had slipped more deeply into an irreversible economic decline, as production levels plummeted, real wages stagnated, shortages increased and foreign debt mounted, reaching $18 billion by 1980 (Paczkowski & Byrne, 2007. p. xxix). In 1980, a Polish Communist Party (PUWP) announcement about increasing food prices triggered a fresh wave of strikes across Poland. At the Lenin Shipyards in Gdansk, workers were further incited by the dismissal of crane driver and trade union activist Anna Walentynowicz, and in response, around 17,000 workers occupied the shipyard on 14 August. On 17 August, the Gdansk strike committee, led by Lech Walesa, drew up a list of ‘21 demands’, which were famously displayed on the gates of the shipyard. While several of the demands were pragmatic (such as improved economic conditions and the right of workers to strike) others were more politicised (including demands for reduced censorship and freedom for political prisoners). Notably, at the top of the list, the strikers demanded the establishment of free trade unions, independent from Communist Party control, to better represent workers’ rights.

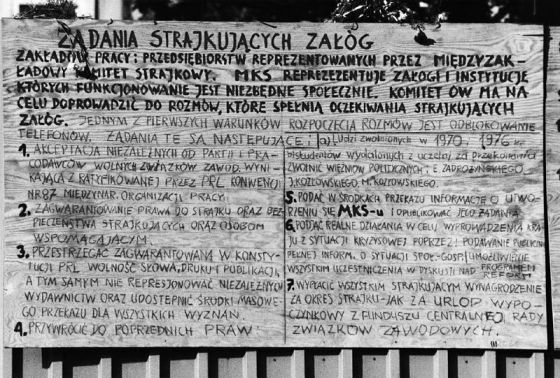

The 21 Demands drawn up by the strike committee, displayed on the gates of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980. Source: http://www.solidarity.gov.pl/?document=61

When the Polish leader, Edward Gierek, turned to Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev for advice, Brezhnev encouraged him to seek a ‘political solution’ rather than forcibly subduing the strikes (having recently sent Soviet troops into Afghanistan, Brezhnev was keen to avoid the possibility of Gierek requesting ‘fraternal support’ from the Soviet military). As a result, the Polish leadership opened negotiations with the striking workers, and on 21 August a Governmental Commission arrived in Gdansk to begin talks, which resulted in the ‘Gdansk Agreement’ of 31 August 1980.

The Gdansk Agreement included authorisation for independent trade union representation of workers’ interests, and on 17 September 1980 the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union Solidarity (NSZZ – Solidarnosc) was officially formed. For the first time since the Communists had come to power the Polish people could join a trade union that was wholly independent from state control. However, Solidarity’s remit was clearly proscribed. The PUWP always intended their role to be limited to non-political representation, as the Gdansk Agreement stated that “these new unions are intended to defend the social and material interest of the workers and not to play the role of a political party”.

THE RISE (AND FALL) OF SOLIDARITY

As Jeffrey Bloom comments ‘‘The strikes of 1980 were the beginning of a social revolution. The nation emerged transformed, they were all aware of what was achieved, strike victory and solidarity helped create a sense of hope and self-confidence for future conflicts” (Bloom, 2013, p115). From its formation in September 1980, Solidarity grew rapidly, peaking with almost 10 million members by June 1981 (a figure which is estimated to have comprised around 70% of all workers in the state economy in Poland and around a third of the total population). Biezenski argues that in the twelve months following their formation, “Solidarity’s dramatic increase in activism was a logical response to a deepening economic crisis within Poland” (Biezenski, 1996, p262). The continued failure of the Communist Party to adequately address deteriorating conditions meant that “the social and material interests of the workers” that Solidarity had been founded to represent remained under threat, and as the months passed, it became increasingly clear that significant improvements to socio-economic conditions in Poland would not be possible without some kind of accompanying political restructuring. Emboldened by their rising support, Solidarity adopted an increasingly politicised stance and began agitating for a general strike. As Barker has argued: “Solidarity changed its members. The very act of participating in a founding meeting, often in defiance of local bosses, involved a breach with old habits of deference and submission. New bonds of solidarity and a new sense of strength were forged … [which] opened the door to a swelling flood of popular demands” (Barker, 2005).

This shift was clearly reflected by October 1981, when Solidarity published their official programme, which encompassed a combination of socio-economic and political aims, couched in increasingly revolutionary rhetoric. The programme attacked the failures and shortcomings of the Communist Party, referred to Solidarity as “a movement for the moral rebirth of the people” and stated that “”History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom … what we had in mind was not only bread, butter and sausage but also justice, democracy and truth”.

“Solidarity unites many social trends and associated people, adhering to various ideologies, with various political and religious convictions, irrespective of their nationality. We have united in protest against injustice, the abuse of power and against the monopolised right to determine and to express the aspirations of the entire nation. The formation of Solidarity, a mass social movement, has radically changed the situation in the country”.

– Solidarity’s Programme, 16th October 1981

As Pittaway points out, ‘The PUWP was thrown into disarray by the advance of Solidarity and its hold over public opinion’ (Pittaway, 2004, p175). Solidarity challenged the status quo, so that the normal mechanisms of communist control over the mass of the population began to break down (Barker, 2005). The Communists initially responded by launching a negative propaganda campaign, designed to damage Solidarity and discredit their leadership, including Walesa. The growing popularity and influence enjoyed by Solidarity also elicited concern from Moscow. On 18 October 1981, General Wojcech Jaruzelski was appointed as new leader of the PUWP. A known hardliner, Jaruzelski was given a clear mandate to suppress Solidarity. Until his death in 2014, Jaruzelski always maintained that he feared Soviet invasion if he had not moved swiftly to contain Solidarity, although the likelyhood of Soviet military intervention in Poland has been disputed. On 13th December 1981, Jaruzelski declared Martial Law and as tanks rolled onto the streets he addressed the people of Poland in a live TV broadcast:

“Our Country stands on the edge of an abyss … Distressing lines of division run through every workplace and through many homes. The atmosphere of interminable conflict, controversy and hatred is sowing mental devastation and mutilating the tradition of tolerance. Strikes, strike alerts and protest actions have become the rule … A national catastrophe is no longer hours away but only hours. In this situation inactivity would be a crime. We have to say: That is enough … The road to confrontation which has been openly forecast by Solidarity leaders, must be avoided and obstructed”.

– From Jaruzelski’s Declaration of Martial Law, 13 December 1981.

General Jaruzelski’s declaration of martial law in Poland, 13 December 1981. Source: http://www.rferl.org/content/Interview_Polands_Jaruzelski_Again_Denies_Seeking_Soviet_Intervention_Against_Solidarity/1902431.html

DEATH – AND REBIRTH

Following Jaruzelski’s declaration of Martial Law, and the creation of a ruling ‘Military Council of National Salvation’ (Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, or WRON), Solidarity was outlawed, its leaders arrested and its supporters repressed. An estimated 5000 Solidarity members were arrested; over 1700 leading figures were imprisoned (including Walesa) and 800,000 others lost their jobs. (Bloom, 2013, p297). Martial Law remained in force in Poland until July 1983.

However, although Solidarity were embattled, the movement survived. During the 1980s, Solidarity networks continued to function underground, focusing their efforts on illegally printing and distributing anti-communist literature, including books, journals, newspapers, leaflets, and posters. On April 12, 1982, ‘Radio Solidarity’ even began broadcasting. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persevered as an exclusively underground organization, promoting civil resistance, continuing their fight for workers’ rights and pushing for social and political change. Former Solidarity member Eva Kulik described how: “”We needed to break the monopoly of the Communist propaganda. And what people really needed was information”. As Feffer points out, the Solidarity trade union actually spent more of its existence in the shadows than as an official movement (Feffer, 2015). However, these underground years were formative in explaining the evolution of the movement. As Touraine has argued, after Jaruzelski forced the movement underground, Solidarity ‘now sought to liberate society – under the cover of a new rhetoric replacing the tired trade union vocabulary with that of a revolutionary movement” (Touraine, 1983, p183).

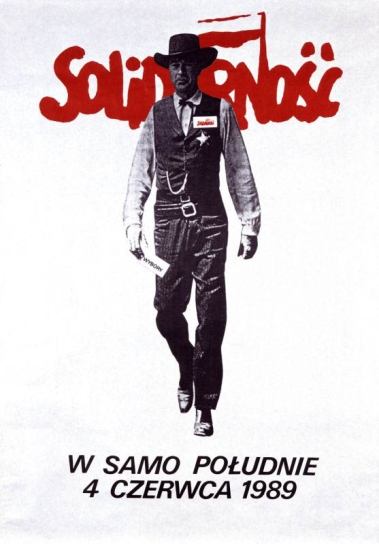

“High Noon” – famous Solidarity campaign poster, used during the Polish elections of June 1989. Source: https://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/699

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev’s appointment as Soviet leader finally bought more of a reformist agenda to the table in Eastern Europe, and by 1988, the Communists were ready to negotiate with Solidarity. Chenoweth believes that by that point the PUWP had little choice: continued economic deterioration in Poland (where rationing had been in place for most of the 1980s) meant that reforms were urgently needed and “the reality by 1988 was that Solidarity was too big and too broad to repress” (Chenoweth, 2014, pp61-62). While they had been driven underground in Poland, Solidarity enjoyed considerable support internationally, with Lech Walesa even being awarded the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 1983. During the famous ‘Round Table talks’ in the spring of 1989, the PUWP agreed to reinstate Solidarity’s original remit as an independent trade union. When Solidarity was re-legalized on 17 April 1989, its membership quickly increased to 1.5 million. However, by now many members of the Solidarity leadership had their eyes firmly on the main political prize. In June 1989, in the first semi-free elections in Poland since 1945, Solidarity represented the main opposition to the PUWP: campaigning as a legal political party, fielding Solidarity candidates against established Party members and sweeping to victory, winning all 161 contested seats in the Sejm [parliament], and 99/100 seats in the Polish Senate. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and in December 1990, Lech Wałęsa was elected President. Solidarity had come a long way from their roots in 1980, and now faced a new challenge: dismantling communism and overseeing Poland’s transformation into a modern, democratic European state.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

KIERAN INGLETON recently completed his BA (Hons) at Leeds Beckett University, graduating with Upper-Second Class honours in July 2015. During the final year of his degree Kieran specialised in the study of communist Eastern Europe, researching the evolution of Solidarity for one of his assessed essays. Kieran is particularly interested in the interaction between politics and society in totalitarian regimes, and his history dissertation explored the application of Totalitarian theory to Stalinism between 1928 and 1939. Kieran now plans to take a gap year, before studying for an MA in Social History.

SOURCES

Colin Barker,(2005) “The Rise of Solidarnosc”, International Socialism, 17 October 2005, http://isj.org.uk/the-rise-of-solidarnosc/

Robert Biezenski (1996), “The Struggle for Solidarity 1980-1981: Two Waves in Conflict”, Europe Asia Studies, 48/2

Jack Bloom (2013), Seeing Through the Eyes of the Polish Revolution: Solidarity and the Struggle against Communism in Poland. Haymarket Books.

Eric Chenoweth (2014) “Dancing with Dictators – General Jaruzelski’s Revisionists”, World Affairs, 10/3, http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/dancing-dictators-general-jaruzelski%E2%80%99s-revisionists

John Feffer (2015) “Solidarity Underground”, The World Post (2015) http://www.johnfeffer.com/solidarity-underground/

Mark Kramer (2011) “The Rise and Fall of Solidarity”, The New York Times, Op Ed http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/13/opinion/the-rise-and-fall-of-solidarity.html?_r=0

Andrzej Paczkowski and Malcolm Byrne. Eds. (2007) From Solidarity to Martial Law: The Polish Crisis of 1980-1981 : A Documentary History. Central European University Press, Budapest.

Mark Pittaway (2004) Eastern Europe 1939-2000. Cambridge University Press.

A Touraine (1983) Solidarity: Poland 1980-1981. Cambridge University Press.

‘Endut! Hoch Hech!’: Confronting Stereotypes About Everyday Life In Communist Eastern Europe.

“ENDUT! HOCH HECH!”: CONFRONTING STEREOTYPES ABOUT EVERYDAY LIFE IN COMMUNIST EASTERN EUROPE – BY CHRIS PRINCE.

Fans of The Simpsons will instantly recognise the titular quote as the caption at the end of this cartoon: ‘Eastern Europe’s favourite cat and mouse team’: Worker and Parasite. Although a rather novel example, ‘Worker and Parasite’ embodies many popular Western stereotypes about communist Eastern Europe. The booming drums and out of tune piano creates a picture of oppression and backwardness; the identical downtrodden men the duo pass by leave an impression of a poverty-stricken and monotonous existence; and the language used is utter gibberish, attributing a sense of incomprehensibility to communism, which is further compounded onscreen by Krusty the Clown’s comment: ‘What the hell was that?’

‘Worker and Parasite’ – ‘Krusty Gets Kancelled.’ (1993), The Simpsons, Season 4,Twentieth Century Fox.

However, was life behind the iron curtain as uniformly grey, bleak and oppressive as is commonly thought? The recent rise of ‘ostalgie’, coupled with the regular publication of survey data claiming that many people believe that at least some aspects of their lives were better under communism, suggests not. There has been growing academic interest in documenting, analysing and attempting to understand experiences of everyday life in communist Eastern Europe in recent years. Today, historians have access to a growing collection of memoirs, interviews and personal testimonies, providing us with a range of first-hand accounts, perspectives and insights about life ‘behind the iron curtain’. When read critically and comparatively, these stories can provide us with a more nuanced, comprehensive understanding of the complexities of everyday life in communist Eastern Europe, as well as challenging some aspects of the most popular stereotypes.

One prominent image that comes to mind when thinking about Communist Eastern Europe is that of widespread material deprivation and poverty. Indeed, the available data shows that by 1973 the economy of East Europe was lagging far behind the West, with the GDP of all Eastern states 30 to 66 percent below the US level . This situation had worsened further by the 1980s, as the many photographs of sparsely stocked shelves and long queues of sad-looking customers standing outside state stores attest. Even when state stores did receive a delivery, many customers complained about the lack of choice available. While Communist Party membership provided access to special socio-economic ‘privileges’ for a select few, economic conditions for the majority were relatively poor, and many individuals highlight material deprivation as a dominant theme when remembering their lives under communism. For example, Simona Baciu described how she could not afford to buy her children any toys, so she collected shoe linings and stripped an old dress to make them stuffed elephants. Baciu also detailed how she and her family had to spend the Romanian winters ‘huddled together next to the stove to gain warmth from each other’ (Baciu in Shapiro, 2004, p.37; p.41). Slavenka Drakulic also explained how private ownership of luxury goods, such as a washing machine, was widely viewed as a marker of economic prestige and social status (Drakulic, 1987, p49).

Shopping behind the iron curtain could be a frustrating and time consuming experience! Photo showing empty shelves in Warsaw (1982). Source: http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/archive/fullsize/Sklep%20miesny,%20Warszawa,%201982,%20by%20Chris%20Niedenthal_2f1befa84f.jpg

However, while many testimonies acknowledge the material deprivation people endured under communism, they also provide some fascinating insights into the ways in which East Europeans coped with the burdens of life in a shortage economy. For example, while Janine Wedel describes the existence of ‘long queues and line committees’ outside empty state stores, she also provides a detailed account of the mechanisms of the informal economy that developed across Eastern Europe in response to economic scarcity, highlighting the etiquette and courtesies required for the establishment of successful ‘Zalatwic’, a complex system of favour exchange, that provided access to goods in short supply. In Wedel’s case, one personal example involved her wooing a local shopkeeper by agreeing to provide her with expensive American coffee to secure the sale of a high quality leather briefcase that was officially ‘out of stock’. As a result of her own experiences, Wedel came to the conclusion that ‘Contrary to the Western perception that no one in Poland can get anything, almost everyone can get something’ – at least, if they were willing to ‘Zalatwic’ (Wedel, 1986, p36; p45).

Wedel also painted a fairly unflattering picture of employment conditions in communist Eastern Europe, characterised by the existence of a generally ‘lackadaisical’ attitude towards work, with employees lazing on the job, cutting their hours short and regularly calling in sick. The popular attitude towards state employment in Eastern Europe was summed up by a well-known communist-era saying “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”. However, Wedel stresses that such ‘lazy’ attitudes applied only to employment within the ‘official’ or state economy, where the lack of motivation and productivity could be explained due to low wages and under-employment. Her study also revealed the enormous time, effort and energy many individuals put into their ‘secondary jobs’ (moonlighting) because they were ‘working for themselves’ in exchange for additional ‘unofficial’ (illegal) income, which was necessary for most people to make ends meet (Wedel, 1986, pp.63-66).

The kind of passive apathy demonstrated towards the state in the workplace was often manifest more openly in the privacy of the home. While the majority of citizens displayed a reasonable level of public conformity, in the relative safety of the private sphere people generally felt more comfortable expressing their discontent and dissatisfaction. Heda Margolius Kovály explained how: ‘During the day people put in their hours at work and fulfilled their party obligations; then they went home, removed their masks, and began to live for a few hours’ (Kovaly, 1986, p.166). Daniela Draghici detailed how people would gather together in their communal kitchens to ‘talk against the government’ and expressed that this kind of ‘private resistance’ was necessary in order to ‘survive communism’ (Draghici in Molloy, 2008). Drakulic also described how, in the Eastern bloc, ‘we are used to swallowing politics with our meals … at dinner you laugh at the evening news, or get mad at the lies that the Communist Party is trying to sell, in spite of everything’ (Drakulic, 1987, pp.16-17). Similarly, resistance could be demonstrated through ‘harmless’ political jokes aimed at the government, which Ben Lewis claimed helped, in part, to ‘laugh communism out of existence’ (Lewis, 2008).

Another popularly held idea about life in communist Eastern Europe, is the perception of an oppressive and ‘grey’ society. Geoffrey and Nigel Swain have argued that by the 1980s, for many East Europeans communism was characterised by ‘the grey Brezhnev years of cynicism, corruption, shortage and falling living standards’ (Swain and Swain, 1993, p.201). Marius Mates, agrees, remembering the commonality of depression; that ‘everybody was so unhappy’ under communism (Mates in Shapiro, 2004, p.79) . Similarly, Slavenka Drakulic argued that the ‘banality of everyday life’ was one of the central fallings of the communist state (Drakulic, 1987, p.18). However, this negative view is tempered by many other individuals who provide more positive accounts of their experiences of life behind the Iron Curtain. For instance, Paula Kirby, a writer who moved to East Germany during the early 1980s, found herself taken aback by the beauty of the urban landscapes and the ‘mass appeal’ the high arts of theatre and opera had obtained due to its accessibility and affordability – a result of generous state subsidies. Zsuzsanna Clark also described fond memories of her schooldays, praising the standard of education that was freely available in communist Hungary, and enthused over her family’s annual vacations to Lake Balaton, emphasising that luxuries such as holidays were only available to many Hungarians because of Communist Party initiatives which had ‘opened up leisure and holiday opportunities…for all” . Similarly parts of Oliver Fritz’s narrative paint a rather idyllic picture of his childhood in East Germany, as he recounts happy memories of time spent playing with friends, sipping fizzy orange lemonade on allotments; helping old ladies cross the street as a proud pioneer (the East German equivalent of the British scouts) ; as well as pulling pranks in the centre of East Berlin by ‘dressing up and acting as lost Westerners’ (Fritz, 2009, p.33; p.46).

Zsuzsanna Clarke playing with her cousins during her happy childhood in communist Hungary. Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1221064/Oppressive-grey-No-growing-communism-happiest-time-life.html

A perpetual housing shortage meant there were long waiting lists for accommodation, so several generations of the same family were often forced to co-habit for extended periods, enduring communism, warts and all, together. This often bought people closer, creating stronger family ties and a stronger sense of community, although for others it was problematic. Drakulic argues that the ‘enforced closeness’ of families ultimately had a detrimental effect, ‘infantilizing’ the younger generation and stifling their will to protest in a ‘geriatric society’ (Drakulic, 1987, pp.88-89). Women’s accounts of their experiences under communism are also notably mixed. Many have praised the increased liberties and the expansion of paid work for women during the communist period. Marie-Luise Seidel, for example, applauded the communist state for the financial support she received as a single mother (Seidel in Molloy, 2008). Nonetheless, as Barbara Einhorn details, despite their increased employment, many did not receive any alleviation from their traditional gender role and therefore endured a ‘dual’ burden in society. For example, Natalia Baranskaya remembers how she endured discrimination at work alongside the burden of caring for her home and family (Einhorn, 1993, pp.46-52) However, many individuals have suggested that the hardships they endured under communism ultimately resulted in the creation of a stronger bond between family and friends, speaking wistfully of the ‘spirit of camaraderie’ that had once prevailed under communism. Similarly, John Feffer has argued that some people now look back on their time during communism, as the “calm life” because: “You generally didn’t have to work hard. You didn’t have to worry about losing your job. Life was simpler. There was only one kind of washing powder. You could count the number of television channels on one hand.”

The process of sharing personal memories is always selective, and we need to bear in mind that individual accounts of life under communism have been influenced by contemporary experiences of post-communism as much as by the ‘reality’ of the past. However, the range of personal experiences and memories highlighted above shows that we need to guard against accepting generalised or over simplified stereotypes about life behind the iron curtain. At times personal testimonies support the conventional image of communist Eastern Europe as grey, depressed, oppressive and poverty stricken. In other ways however, they contrast or even challenge many of these accepted stereotypes, illustrating that sometimes people not only survived communism but benefited from it. Personal narratives attest to the many complexities of navigating life behind the iron curtain, enabling us to gain a deeper understanding of life in communist Eastern Europe, while also reconsidering certain aspects of its more conventional image.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CHRIS PRINCE has recently completed his BA (Hons) in History at Leeds Beckett University, graduating with first class honours in July 2015. During his final year of study, Chris studied Communist Eastern Europe and he researched experiences of everday life in Eastern Europe for one of his assessed essays. Chris is now planning to study for an A+ certification.

SOURCES

‘Krusty Gets Kancelled’ (1993) The Simpsons, Season 4, Twentieth Century Fox.

Clark, Z. (2009) ‘Oppressive and Grey? No, growing up under communism was the happiest time of my life.’ Daily Mail 17/10/2009, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1221064/Oppressive-grey-No-growing-communism-happiest-time-life.html

Drakulic, S. (1987) How we Survived Communism and Even Laughed. London: Vintage.

Einhorn, H. (1993) Cinderella Goes to Market: Citizenship, Gender and Women’s movements in East Central Europe. London: Verso.

Feffer, J (2013) ‘Remembering the Calm Life Under Communism’, The Huffington Post 02/12/2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-feffer/remembering-the-calm-life_b_2671955.html

Fritz, O. (2009) The Iron Curtain Kid. Raleigh: Lulu Press. See also: http://www.ironcurtainkid.com/

Kirby, P and Hignett, K. (2014) ‘Paula Kirby on Life in the GDR’ The View East, https://thevieweast.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/paula-kirby-on-life-in-the-gdr/

Kovály, H.M. (1986) Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague. 1941-1968. London: Granta.

Lewis, B. (2008) Hammer and Tickle: A History of Communism Told Through Communist Jokes. London: Phoenix.

Molloy, P. (2008) The Lost World of Communism: A History of Daily Life Behind the Iron Curtain. BBC Worldwide.

Shapiro, S.G. (2004) The Curtain Rises: Oral Histories of the Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. London: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers.

Swain, G and Swain, N. (1993) Eastern Europe Since 1945. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Wedel, J. (1986) The Private Poland. New York: Facts on File.

Fearsome or Futile? The Limitations of Stasi Surveillance in East Germany.

FEARSOME OR FUTILE? THE LIMITATIONS OF STASI SURVEILLANCE IN EAST GERMANY – BY LUCY COXHEAD.

The East German Ministry of State Security (commonly known as the ‘Stasi’), exercised unquestionably high levels of surveillance and social control over the East German population from their establishment in 1950, until their dissolution following the revolution of 1989. The Stasi described itself as the ‘Sword and Shield’ of the Communist Party, symbolically reflecting the fearsome reputation they enjoyed, both inside the GDR and overseas. The power and influence of the Stasi has been well documented in both academic studies, personal testimonies and depicted in films such as The Lives of Others (2006) and Barbara (2012) demonstrating how East German citizens were subject to incessant and intrusive monitoring, with the result that thousands experienced restrictions on their mobility and their freedom to publicly express or communicate both personal and political views. There are even numerous reports of family members spying on one another. What has been less well-documented, however, were the limitations to Stasi influence in the GDR. Despite their powerful and fearsome reputation, the Stasi’s desire to ‘know everything about everyone’ was ultimately inconceivable. While this topic remains under-studied, more recent research has revealed the existence of numerous mistakes in Stasi files, highlighted certain limitations to Stasi surveillance, and illustrated the continued ability of many individuals to subvert Stasi influence. Together, these mechanisms helped to undermine, and ultimately destroy, Stasi control over the East German population.

STASI SURVEILLANCE TACTICS

The Stasi was established in 1950, to help the East German Socialist Unity Party (SED) wage a cold war against both domestic and ‘Western’ enemies. Betts argues that the power of the Stasi was built on ‘a severe code of conformity and model citizenship’ (Betts, 2010, p13). As the Stasi developed, their operational remit expanded rapidly, as did their staff base, with a growing number of full-time Stasi agents supported by a much broader network of spies and informers, recruited from their own citizenry. Shortly before their dissolution at the end of 1989, records indicate that the Stasi employed 91,105 full time staff and about 176, 000 informers to watch over a population of 16.4 million, with recent research suggesting that the general practice of ‘snitching’ among East German society was also much more widespread than previously thought. The extent of Stasi operations is also revealed by the sheer extent of the archival holdings, with shelves of files that stretch for 180 kilometres (Dennis, 2003, p. 7).

Photo of some of the surviving Stasi files, housed in an archive which stretches for 180km. Source: http://thecubaneconomy.com/articles/2011/12/johann-sebastian-bach-the-%E2%80%9Cstasi%E2%80%9D-and-cuba/

Between 1950 and 1989 the Stasi took surveillance to unprecedented levels in their attempts to gather ‘deep knowledge’ about all aspects of their citizens’ lives, with the use of intrusive techniques including extensive monitoring of both postal and telephone communications, the bugging of workplaces, social spaces and private homes, and human surveillance. One former Stasi officer who was interviewed by Anna Funder revealed various tactics they used to compile information, including the existence of a ‘coding villa’, where Stasi officers regularly encoded transcripts of thousands of telephone conversations and the use of officers in civilian clothes or various disguises to make observations on the ground, often assisted by the concealment of recording devices and cameras in coats and bags. Funder alleges that the Stasi even used radiation marking to track objects and people, in their attempts to know as much as possible about their perceived enemies (Funder, 2004, p153, p.191)

Photo of Stasi surveillance gear on display at the Stasi museum in Berlin. Source: http://egorfine.livejournal.com/464589.html

The information collected was used to manipulate and control the population, and it is clear that in many cases the Stasi had the ability to directly influence and disrupt people’s lives, using their power to ‘punish’ unruly citizens. Ulrike Poppe, an East German dissident, was subjected to intensive Stasi surveillance and harassment after she refused their ‘invitation’ to become an informer, and later discovered that not only had her own house and telephone been bugged, but her friends’ bedrooms were also bugged and video cameras were installed in the apartment across the street, to enable the Stasi to watch her every move. ‘Julia’ also became a Stasi target after she developed a relationship with an Italian businessman who had visited the GDR. When she was interviewed by Anna Funder for her book Stasiland, Julia described how at first, although she often heard strange noises on her telephone, and her personal letters frequently arrived opened, with stickers claiming they had been ‘damaged in transit’, she underestimated the malevolent reach of the Stasi, even laughing off their initial interest in her:

“I lived with this sort of scrutiny as fact. I didn’t like it, but I thought: I live in a dictatorship, so that’s just how it is … When I hung up [the telephone] I’d say goodnight … and then I’d say ‘Night all!’ to the others listening in. I meant it as a joke … if you took things as seriously as people in the West think we must have, we would have all killed ourselves!

I’d say to myself: look it can’t be that bad! What can they do to me? I mean, I wasn’t afraid they’d collect me in the night and lock me up and torture me”

– From Julia’s Story, in Funder, Stasiland, p.99; pp 106-107.

However, Julia went on to describe how the Stasi were subsequently responsible for her exclusion from education and employment, effectively isolating her within East German society and deliberately subjecting her to high levels of psychological trauma and personal humiliation as their campaign against her escalated, before ultimately attempting to recruit her to work for them as an informant in exchange for allowing her an ‘easier’ life in the GDR – an offer which she successfully resisted. After this, Julia saw that the power of the Stasi ‘can be so dangerous, so very dangerous, without me having done anything at all’ (Julia quoted in Funder, 2004, p114). These cases effectively illustrate how, in many cases, by preying on members of a society who attempted to live their lives as normally as possible under the pressures of Communist control, the Stasi had the ability to essentially turn East Germans into prisoners within their own country. However, while evidence suggests that many East German citizens did agree to spy for the Stasi, the refusal of either Ukrike or Julia to succumb to Stasi pressure to inform also illustrates the capacity of others for resistance and defiance.

THE LIMITATIONS OF STASI SURVEILLANCE

The Stasi were undoubtedly a powerful and fearsome presence in communist East Germany, with the ability to influence and even destroy people’s lives. However, there were still some limitations to their influence. Despite their ruthless monitoring, the Stasi aim to discover ‘everything about everyone’ was not feasible, and the popular myth of the Stasi as all-encompassing, ultra-efficient and omnipotent force can be challenged. Herr Bock, a committed former Stasi officer interviewed by Anna Funder, confirmed that he thought that, over time, the expansion of the Stasi’s operational remit became so broad that it was ‘too wide to be carried out…within available resources’ (Funder, 2004, p.200) Over time, the Stasi began to struggle to process the large amounts of information they were recording, as agents were overwhelmed by a flood of data, much of it mindless trivia, meaning that sometimes even potentially significant information was missed or overlooked. Paula Kirby, a British citizen who worked as a teacher in the GDR during the 1980s (making her an obvious target for Stasi surveillance), described how their presence made her ‘cautious but not paranoid: after all, I wasn’t spying, I wasn’t trying to foment revolution and I wasn’t a subversive element, so I couldn’t imagine they’d find anything of interest to them even if they were watching me’ (Hignett & Kirby, 2014). Access to Stasi files has indeed shown that agents often recorded vast amounts of unnecessarily banal information about their subjects, such as ‘where Comrade Gisela kept her ironing board… and how many times a week Comrade Armin took out his garbage’ (Dennis, 2003, p. 3). Similarly, when Ulrike Poppe gained access to her own Stasi files, she discovered that most of the information recorded from years of intensive surveillance “was just junk.” (Curry, 2008).

Photo of Paula Kirby, working at the Technical University in Dresden, SIZ office (1986). Source: https://thevieweast.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/paula-kirby-on-life-in-the-gdr/

Paula Kirby also states that despite its fearsome reputation today, the Stasi was capable of almost ‘farcical incompetence’. For example, a letter in her file dated February 1988, referred to her as still being resident in Dresden, although she had actually been back in the UK for nearly six months by then. Kirby also described how she once spent several hours “in full view” of Stasi officers with a British Embassy official, discussing controversial matters like Gorbachev’s reforms and the recent GDR elections, stating that this ‘couldn’t have made things any easier for them if we’d tried’. Yet, the information recorded in her file showed that the Stasi still managed to ‘miss all the interesting bits’ (Hignett & Kirby, 2014). British journalist and academic Timothy Garton-Ash also cross-checked the information recorded in his file with his personal diaries, and detected several mistakes, including information recorded about one journey he made to Poland, where the date recorded was wrong by three months. Despite being subjected to heavy surveillance, Garton-Ash still successfully collected defamatory material about the GDR and continued to publish his work in the West (including a tribute to Robert Havemann, a prominent East German dissident), also broadcasting for the BBC in Berlin using a pseudenom (Garton-Ash, 2009, p.56). Many other ordinary East German citizens also developed ways of avoiding Stasi surveillance, and successfully carved out spaces where they could communicate more freely. While most people continued to conform within the public sphere, by watching what they said and did, the private sphere became a place of freedom, dissent and resistance in the GDR, with ties between families, friends and communities often strengthening rather than weakening, despite the pressure of the system (Gieseke, 2014, p120).

FEARSOME OR FUTILE?

Despite their best attempts, the Stasi were ultimately unable to fulfil their desire to ‘know everything about everyone’. The Stasi undoubtedly maintained a fearsome presence in East Germany until 1989, and many victims of Stasi repression are still living with the consequences today. However, the available evidence suggests that as their operational remit expanded, Stasi officers were flooded with high levels of meaningless data, so that important details were often overlooked and mistakes were sometimes made. During the final years of communism in East Germany, open dissent and individual resistance increased, despite continued pressure from the Stasi. New dissident movements such as the Initiative for Peace and Human Rights were founded, non-conformist bands such as the Klaus Renft combo and the Puhdys resisted Stasi repression by singing lyrics reflecting rebellion, poignancy and hope, while ‘anti-communist’ youth cultures such as punks, hippies and skinheads railed against state attempts to regulate individuality and self-expression. Ultimately, despite enjoying high levels of power and influence, the Stasi proved to be incapable of controlling the rising social, economic and political currents to hold back the tide of change in East Germany.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LUCY COXHEAD has recently completed her BA (Hons) in History at Leeds Beckett University and will graduate with first class honours in July 2015. Lucy is also a co-recipient of the Deans prize for Outstanding Student Achievement in History in 2014-15. During her final year of study, Lucy studied Communist Eastern Europe, where she specialised in researching the role of the Stasi for one of her assessed essays. Her history dissertation researched the emotional impact of World War One, revealed through soldiers’ diaries. She is now planning to work for a year before thinking about continuing her academic studies at postgraduate level.

SOURCES

Betts, P. (2010) Within Walls: Private Life in the German Democratic Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruce, G. (2010) The Firm: The Inside Story of the Stasi. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cook, D. (2011) ‘Living with the Enemy: Informing the Stasi in the GDR,’ The View East.

Curry, C. (2008) ‘Piecing Together the Dark Legacy of East Germany’s Secret Police’, Wired.Com

Dennis, M. (2003) The Stasi: Myth and Reality. New York: Routledge.

Funder, A. (2004) Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall. London: Granta.

Garton-Ash, T. (2009) The File. London: Atlantic Books.

Gieseke, J. (2014) The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police, 1945-1990. New York: Berghahn Books.

Hignett, K and Kirby, P (2014) ‘Interview: Paula Kirby on Life in the GDR’, The View East.

Shingler, J (2011) ‘Rocking the Wall: East German Rock and Pop in the 1970s and 1980s’. The View East.

The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia

THE RISE OF COMMUNISM IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA – BY SAM SKELDING

On 25th February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, led by Klement Gottwald, officially gained full power over the country. The communist rise to power was dubbed ‘Victorious February’ during the Communist era, and was celebrated each year, although since 1989 it has been more popularly referred to in slightly less positive terms, as ‘the February Coup’. It had taken just three short years for the communists to gain full control of Czechoslovakia following the end of World War II, but, by the standards of other East European countries, they were fairly late in establishing power. Just how did the communists managed to rise to the top in a country that had previously been heralded by many as a beacon of democracy and perceived as one of the most ‘Western oriented’ countries within central and eastern Europe? This article will explore some of the different factors that combined to create a climate favourable to the Communist Party’s ascension to power in Czechoslovakia after World War II.

WWII AND AFTER

Eastern Europe bore some of the worst experiences of World War II. It was here in the ‘bloodlands’ of Europe that the scars the war left behind were felt most keenly, and Czechoslovakia was no exception. Bradley Abrams has argued that WWII served ‘as both a catalyst of, and a lever for communism [in Czechoslovakia] … creating the intellectual and cultural preconditions for the Communist Party’s rise to total power’ after 1945 (Abrams 2004, p.105).

Although Czechoslovakia recovered most of its pre-WWII territory after 1945, in other ways things looked very different. Firstly, the ethnic and social makeup of Czechoslovakia changed significantly as a result of World War II. During the years of Nazi dominance, German ‘colonists’ began to move into the country whilst many Czechs and Slovaks were deported to forced labour camps or murdered. By 1945, 3.7 percent of the pre-war Czech population had died, including more than a quarter of a million Czechoslovakian Jews, who perished in the concentration camps (Applebaum, 2012, p.10). At the end of the war there was further significant population movement as President Benes authorised the organised expulsion of most of the 3 million ethnic Germans and Hungarians who were resident in Czechoslovakia, whilst thousands of other survivors gradually returned from labour and concentration camps. The decimation of various minority groups (including Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Jews and Roma) meant that following the end of the war, Czechs and Slovaks comprised 90% of the country’s population. This led to heightened nationalism which was subsequently manipulated by the Communist Party, ‘since they could take credit for providing opportunities for mobility and for satisfying nationalist aspirations.’ (Gross, 1989, p.203).

Economically, Czechoslovakia was also transformed by the war. During the years of Nazi occupation and dominance, many businesses were nationalized as the economy was reoriented towards the German war effort, turning Czechoslovakia into more of a ‘closed market’. When the war ended, Czechoslovakia retained a semi-nationalised domestic economy with few remaining international trade links, circumstances which made it easier for the Soviet Union to dominate Czechoslovakia’s post-war economic recovery, which ultimately, laid the groundwork for the post-war shift to Soviet style ‘central planning’. This is illustrated by the fact that, at the end of the War, returning Czechoslovakian President Eduard Benes asked Klement Gottwald, leader of the Communists, to work with the Social Democrats to prepare a decree to nationalise the remaining Czechoslovakian industry (a policy later evidenced in the April 1945 Košice Programme), which met little political opposition.

Czechoslovakia’s international relations also underwent a significant shift after 1945. The perceived failure of their previous political reliance on the West was confirmed after Czechoslovakia became the most famous victim of appeasement with the 1938 Munich agreement (which famously ceded part, and eventually all, of Bohemia to Germany), creating strong feelings of bitterness and insecurity.

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

—Neville Chamberlain, 27 September 1938.

British Prime Minister Neville Chaimberlain’s declaration that the Munich agreement, ceding control over Czechoslovakian territory to Hitler, would secure ‘peace in our time’. Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/nevill3.jpg

Cashman has subsequently argued that, in many ways, ‘the events of 1938 paved the way for the imposition of communism in Czechoslovakia.’ (Cashman, 2008, p.1647). This shift was later compounded when it was the Soviet Red Army who arrived to liberate most of Czechoslovakia from German control in 1945. The fact that it was the Soviets who, as Winston Churchill famously acknowledged, had ‘torn the guts out of Hitler’s war machine’ and secured Czechoslovakia’s freedom, increased Communist prestige in Czechoslovakia. The power and brutality many Czechoslovaks experienced at the hands of the Red Army during and after their liberation (in Czechoslovakia, as elsewhere in ‘liberated’ Eastern Europe, numerous cases of theft, violence and rape committed by Soviet soldiers were recorded) created an aura of fear and admiration around the USSR, as Applebaum remarked ‘The Red Army was brutal, it was powerful and it could not be stopped’ (Applebaum, 2012, p.32).

Finally, there was also widespread popular enthusiasm for social change in Czechoslovakia, which broadly supported a general political shift to the left and towards a more radical, socialist agenda at the end of World War II. Jo Langer described the change in public feeling after 1945, as ‘now the task was to erase the interruption and effects of the war and to help this country ahead on the old road to an even better future’ (Langer, 2011, p.27) while Marian Slingova suggested that ‘socialism in one form or another was the goal for many in those days. In Czechoslovakia, a revolution was in progress.’ (Slingova, 1968, p.40). Heda Margolius Kovaly explained how many who had lived through World War II ‘came to believe that Communism was the very opposite of Nazism, a movement that would restore all the values that Nazism had destroyed, most of all the dignity of man and the solidarity of all human beings’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.64). This all translated into increased levels of support for the Communist Party, who won 114 out of 300 contested seats, and 38 % of the popular vote in the May 1946 election, which, coupled with the support of their socialist allies, gave them a slim political majority of 51%. Robert Gellately has acknowledged that while non-communists were ‘shocked’ by this result, they ‘admitted that the [Czechoslovakian] elections were relatively free and not stolen, as they were elsewhere in Eastern Europe’ (Gellately, 2013, p.233).

THE COMMUNIST PATHWAY TO POWER

Following World War II, a National Government was formed in Czechoslovakia, comprised of 25 ministers, 9 of whom were Communist Party members. From the outset, the Communists were in an influential position, controlling some of the most important government ministries, with a political mandate to launch a sweeping programme of post-war, reform, with explicitly socialist and nationalist aims. Several key post-war politicians, including President Eduard Benes and Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, initially hoped they could work with the communists, while holding out hope that the Western powers would not simply stand by whilst Czechoslovakia fell to Soviet control, despite their bitter experience in 1938 (Lukes, 1997, p.255).

While many Czechoslovakians broadly supported the communist agenda, they hoped for the freedom to develop their own, independent, ‘national road to socialism’. However, between 1946-1948, the Czechoslovakian communists came under increasing Soviet pressure, both to secure sole power, and to conform to Stalinist-style socialism. In July 1947, Stalin’s show of displeasure with the Czechoslovak government’s initial willingness to accept U.S. Marshall Aid forced an immediate reversal of their decision, firmly illustrating the nature of the relationship between the two states. Czechoslovakian Foreign Minister (and non-communist) Jan Masaryk summed up his feelings, about the enforced refusal of Marshall Aid, when he declared that : “I went to Moscow as the Foreign Minister of an independent sovereign state; I returned as a lacky of the Soviet Government.”’ (Lukes, 1997, p.251). Stalin also used the founding conference of the Cominform in September 1947 to publicly criticise the French, Italian and Czechoslovakian Communist Parties for ‘allowing their opportunity to seize power to pass them by’, while the subsequent expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform in June 1948 sent a clear signal to the Czechoslovak communist leadership that the “national roads” policy was no longer supported by the Soviets.

Portraits of Klement Gottwald and Joseph Stalin at a 1947 meeting of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Gottwald_%26_Stalin.jpg

The mechanisms and intrigues surrounding the communist seizure of power in Czechoslovakia have been well documented. During 1947 – 1948 the Communist Party positioned themselves tactically, and one CIA intelligence report recognized that, ‘Having won the key cabinet positions in the May 1946 elections … the Communists have since steadily extended their control of the positions necessary for seizure of the government.’ (CIA, 1948).

By 1948, it appeared that the tide was starting to turn against the Communists, as their coalition partners became increasingly critical of their political tactics. In January 1948, controversy erupted after the communist controlled Minister of the Interior sacked a number of police officials who were not Communist Party members, leading their coalition partners to call for a full cabinet investigation Following this, on 10th February 1948, the socialist minister for the Civil Service won government support for a pay deal that had been strongly opposed by both the communists and the trade unions. However, Klement Gottwald successfully delayed the cabinet from returning to this issue until finally, on 20th February 1948, government ministers from the National Socialists, People’s Party and Slovak Democrats all resigned, in the hope of forcing new elections to reduce the communist’s influence in government. However, the Social Democratic ministers chose to side with the communists and refused to resign, which meant that together the two parties retained over half of the seats in parliament. Gottwald’s position was strengthened by the outbreak of large pro-communist demonstrations in Prague – largely orchestrated by the communists, but with some degree of popular support – so that rather than calling new elections, on 25th February President Benes agreed to the formation of a new government, dominated by the communists and their socialist allies.

As Klement Gottwald triumphantly addressed the crowds, Heda Margolius Kovaly recalled one elderly man’s reaction ‘the old gentleman was standing at the window, looking down at the crowded street. He did not even turn around to greet me. He said, very quietly, “This is a day to remember. Today, our democracy is dying” … Out in the street, the voice of Klement Gottwald began thundering from the loudspeakers.’ (Kovaly, 2012, p.74).

Pro-Communist demonstrations in Prague, February 1948. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Czechoslovak_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat#/media/File:Agitace-1947.jpg

Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader Klement Gottwald, addressing the crowds in Wenceslas Square, Prague, on 25 February 1948. Source: https://www.private-prague-guide.com/wp-content/klement_gottwald.jpg

Within weeks the socialists had agreed to formally merge with the communists and the subsequent elections in May 1948 (which were considerably less free than those of 1946!) resulted in the Communist Party gaining over 75 percent of the seats) and on 9 May 1948 a new constitution defined Czechoslovakia as a ‘People’s Republic’ (Swain & Swain, 1993, p64). A one party state had been created in Czechoslovakia, which was rapidly brought under firm Soviet control. From 1948 the Communists were forced to abandon any remaining efforts to retain ‘national’ socialism in Czechoslovakia, in favour of ensuring their country firmly fitted the Stalinist mould.

You can hear more about the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia in this video from the US National Archives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAM SKELDING recently completed his BA (Hons) in History at Leeds Beckett University and will graduate in July 2015. During his final year of study, Sam specialised in the study of Communist Eastern Europe. His history dissertation explored the rise of communism in Czechoslovakia, and was titled “‘Our Democracy is Dying’: The Rise of Communism in Czechoslovakia and its Immediate Aftermath, 1945-1953”. Sam has been awarded a postgraduate bursary at Leeds Beckett, and will begin studying for an MA in Social History in September 2015.

SOURCES

Applebaum, A, (2012), Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56. Allen Lane

Abrams, B (2004) The struggle for the soul of the nation : Czech culture and the rise of communism. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: Maryland.

Abrams, B (2010) ‘Hope Died Last: The Czechoslovak Road to Socialism’ In Tismaneanu, V. Ed. Stalinism Revisited: The Establishment of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press pp.345-367

Cashman, L (2008) ‘Remembering 1948 and 1968: Reflections on Two Pivotal Years in Czech and Slovak History’, Europe-Asia Studies, 60/10, 1645-1658.

C.I.A (1948) ’62 Weekly Summary Excerpt, 27 February 1948, Communist Coup in Czechoslovakia; Communist Military and Political Outlook in Manchuria’[Internet]< https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/assessing-the-soviet-threat-the-early-cold-war-years/5563bod2.pdf>%5BAccessed on 9 April 2015]

Gross, J, ‘The Social Consequences of War: Preliminaries for the Study of the Imposition of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe’, East European Politics and Societies, 3 (1989) pp.198-214.

Gellately, R. (2013) Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kovaly, H. (2012) Under a Cruel Star: My Life in Prague 1941-1968. London: Granta

Langer, J. (2011) Convictions: My Life With A Good Communist. London: Granta.

Lukes, I (1997) ‘The Czech Road to Communism’ In Naimark, N and Gibianskii, L The Establishment of Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe 1944-1949. Westview Press.

Slingova, M (1968) Truth Will Prevail, London: Merlin Press.

Swain G and Swain N (1993) Eastern Europe since 1945. Basingstoke: Macmillan

25 years since the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Last weekend marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event which is remembered today as one of the iconic moments of the East European revolutions of 1989. Of course, the fall of the wall and the capitulation of the communist regime in East Germany did not represent the beginning of the changes that swept the communist bloc during that tumultous year – by 9th November 1989 Solidarity had already achieved electoral success in Poland, and the Hungarian communist party had announced sweeping reforms, proposed democratic elections and opened up their borders with the West – a move that also directly contributed to the final destabilisation of the communist regime in East Germany. Neither did the fall of the wall signal the end of the East European revolutions: the following day Bulgarian leader Todor Zhivkov announced his resignation after 18 years in power, later in November the Velvet Revolution led to the end of communist rule in Czecholovakia and in December the Romanian Revolution resulted in the Christmas Day execution of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena. However, between its construction in August 1961 and its destruction in November 1989, the Berlin Wall came to symbolise the ‘Iron Curtain’ that separated Western Europe from the communist Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, so when the Wall finally crumbled and live images showing thousands of Germans celebrating by hacking at the hated structure with hammers and pick-axes were transmitted around the world, it created one of the most iconic moments of the revolutions of 1989, the collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War. As Soviet foreign policy advisor Anatoly Chernayev recorded in his diary on 10th November 1989: “The Berlin Wall has collapsed. This entire era in the history of the socialist system is over … This is the end of Yalta … the Stalinist legacy and “the defeat of Hitlerite Germany”.

Twenty five years on, the fall of the Berlin Wall is remembered as an iconic moment during the the revolutionary year of 1989.

Although I was still only a child, I do remember the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. I remember sitting transfixed in front of the TV, watching ‘John Craven’s Newsround’ on CBBC, as footage of the collapse of the wall and the first emotional meetings between Germans from East and West was shown. While I wasn’t old enough to really understand what was going on, I do remember the vivid sense that something *really* important was happening – the first sense I ever had of ‘living through history’. That feeling stayed with me over the years, and I have often wondered whether that was the reason why I became so interested in Central and East European history, eventually making a career out of it!

Five years ago, in November 2009, I was also lucky enough to be able to visit Berlin for the 20th anniversary ‘Mauerfall’ celebrations, as giant dominoes were set up following the former route of the Wall, before being symbolically toppled on the evening of 9th November:

Viewed from the Reichstag, giant dominoes snaking through the centre of Berlin – part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in Novembr 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Giant dominoes lined up along the former route of the Berlin Wall, November 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

This year, a different kind of installation – a ‘border of light’ or ‘Lichtgrenze‘ was created in Berlin, comprised of 8000 illuminated balloons that were then released, one by one, on the evening of 9th November 2014:

Although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin, the power of the internet meant I could still watch the release of the balloons and the dramatic firework finale from the comfort of my own sofa on Sunday evening via the official livestream. Granted, it wasn’t as good as actually being in Berlin, but alongside the proliferation of photos and videos posted on Twitter, it was a pretty good substitute!

However, although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin this year, I was able to organise an event to commemorate the 25th anniversary here at Leeds Beckett University, through our Centre for Culture and the Arts. Invited guest speaker Oliver Fritz, author of the critically acclaimed book The Iron Curtain Kid visited and spoke about his experiences of growing up ‘on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall’ in communist-controlled East Berlin, and about witnessing the fall of the Wall in November 1989. Oliver provided some fascinating – and often very humorous – insights into life in communist East Germany, attracting a lively audience comprised of staff, students and members of the public. Oliver’s talk was followed by a screening of the Oscar-winning film The Lives of Others (2007), a critically acclaimed portrayal of a Stasi agent assigned to conduct surveillance on a writer suspected of dissident activities in East Berlin during the 1980s.

Oliver Fritz, author of ‘The Iron Curtain Kid’ talking about his experiences of growing up in East Berlin at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett

Oliver Fritz and Kelly Hignett demonstrating East German speech etiquette to an enthusiastic audience! Photo © Dr. Zoe Thompson.

A special exhibition, produced by Leeds Beckett students studying for a BA in Graphic Arts and Design (working with GAD Senior Lecturer Justin Burns), in collaboration with some of our final year BA History undergraduates was also displayed to mark the event. The impressively detailed and striking exhibition functioned as a visual timeline, spanning the initial division of Germany after WWII until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989: