25 years since the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Last weekend marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event which is remembered today as one of the iconic moments of the East European revolutions of 1989. Of course, the fall of the wall and the capitulation of the communist regime in East Germany did not represent the beginning of the changes that swept the communist bloc during that tumultous year – by 9th November 1989 Solidarity had already achieved electoral success in Poland, and the Hungarian communist party had announced sweeping reforms, proposed democratic elections and opened up their borders with the West – a move that also directly contributed to the final destabilisation of the communist regime in East Germany. Neither did the fall of the wall signal the end of the East European revolutions: the following day Bulgarian leader Todor Zhivkov announced his resignation after 18 years in power, later in November the Velvet Revolution led to the end of communist rule in Czecholovakia and in December the Romanian Revolution resulted in the Christmas Day execution of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena. However, between its construction in August 1961 and its destruction in November 1989, the Berlin Wall came to symbolise the ‘Iron Curtain’ that separated Western Europe from the communist Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, so when the Wall finally crumbled and live images showing thousands of Germans celebrating by hacking at the hated structure with hammers and pick-axes were transmitted around the world, it created one of the most iconic moments of the revolutions of 1989, the collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War. As Soviet foreign policy advisor Anatoly Chernayev recorded in his diary on 10th November 1989: “The Berlin Wall has collapsed. This entire era in the history of the socialist system is over … This is the end of Yalta … the Stalinist legacy and “the defeat of Hitlerite Germany”.

Twenty five years on, the fall of the Berlin Wall is remembered as an iconic moment during the the revolutionary year of 1989.

Although I was still only a child, I do remember the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. I remember sitting transfixed in front of the TV, watching ‘John Craven’s Newsround’ on CBBC, as footage of the collapse of the wall and the first emotional meetings between Germans from East and West was shown. While I wasn’t old enough to really understand what was going on, I do remember the vivid sense that something *really* important was happening – the first sense I ever had of ‘living through history’. That feeling stayed with me over the years, and I have often wondered whether that was the reason why I became so interested in Central and East European history, eventually making a career out of it!

Five years ago, in November 2009, I was also lucky enough to be able to visit Berlin for the 20th anniversary ‘Mauerfall’ celebrations, as giant dominoes were set up following the former route of the Wall, before being symbolically toppled on the evening of 9th November:

Viewed from the Reichstag, giant dominoes snaking through the centre of Berlin – part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in Novembr 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Giant dominoes lined up along the former route of the Berlin Wall, November 2009. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

This year, a different kind of installation – a ‘border of light’ or ‘Lichtgrenze‘ was created in Berlin, comprised of 8000 illuminated balloons that were then released, one by one, on the evening of 9th November 2014:

Although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin, the power of the internet meant I could still watch the release of the balloons and the dramatic firework finale from the comfort of my own sofa on Sunday evening via the official livestream. Granted, it wasn’t as good as actually being in Berlin, but alongside the proliferation of photos and videos posted on Twitter, it was a pretty good substitute!

However, although I wasn’t able to visit Berlin this year, I was able to organise an event to commemorate the 25th anniversary here at Leeds Beckett University, through our Centre for Culture and the Arts. Invited guest speaker Oliver Fritz, author of the critically acclaimed book The Iron Curtain Kid visited and spoke about his experiences of growing up ‘on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall’ in communist-controlled East Berlin, and about witnessing the fall of the Wall in November 1989. Oliver provided some fascinating – and often very humorous – insights into life in communist East Germany, attracting a lively audience comprised of staff, students and members of the public. Oliver’s talk was followed by a screening of the Oscar-winning film The Lives of Others (2007), a critically acclaimed portrayal of a Stasi agent assigned to conduct surveillance on a writer suspected of dissident activities in East Berlin during the 1980s.

Oliver Fritz, author of ‘The Iron Curtain Kid’ talking about his experiences of growing up in East Berlin at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett

Oliver Fritz and Kelly Hignett demonstrating East German speech etiquette to an enthusiastic audience! Photo © Dr. Zoe Thompson.

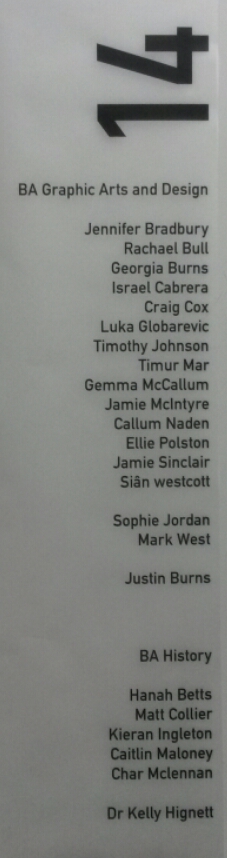

A special exhibition, produced by Leeds Beckett students studying for a BA in Graphic Arts and Design (working with GAD Senior Lecturer Justin Burns), in collaboration with some of our final year BA History undergraduates was also displayed to mark the event. The impressively detailed and striking exhibition functioned as a visual timeline, spanning the initial division of Germany after WWII until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989:

Oliver Fritz admiring part of the 25th Berlin Wall fall anniversary exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

‘Mini Berlin Wall’ – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Timeline style wall display – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Timeline style wall display – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

Two perspectives: 1961 and 1989. Installation displayed as part of 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

‘Bricks from the Berlin Wall’ – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Berlin Wall Bricks' [print] - student artwork displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/bricks-print-crop.jpg?w=620&h=422)

‘Berlin Wall Bricks’ [print] – student artwork displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['25 years since Mauerfall' [print] - student art work displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/2014-11-07-22-43-44.jpg?w=350&h=507)

’25 years since Mauerfall’ [print] – student art work displayed at 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Hammering down the Wall' [print] - 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/hammer-pic.jpg?w=324&h=555)

‘Hammering down the Wall’ [print] – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

!['Two Berlins' [print] - 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.](https://thevieweast.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/tightrope-faces-crop.jpg?w=479&h=325)

‘Two Berlins’ [print] – 25th Anniversary Berlin Wall Fall exhibition, produced by students from Graphic Arts and Design and History, displayed at Leeds Beckett University. Photo © Kelly Hignett.

You can read more about the event here.

Finally, the 25th anniversary commemorations have recived a lot of media attention and online coverage. Here is a short collection of some of my favourite features from the past week:

- This great RFERL infographic – 25 Years Later: The European Revolutions – for the ‘bigger picture’ of what was happening in 1989.

- The 25 Years Iron Curtain Twitter feed – who are tweeting short reports about key events that took place in Eastern Europe in 1989.

- This short video on Vine – The History of the Berlin Wall in 60 Seconds

- Special CWIHP documentary collection – 25th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

- The Berlin Wall in Google Street View

- The Guardian’s interactive photo gallery of the Berlin Wall in the Cold War and Now

- The Berlin Wall – Before and After – photos in the Washington Post.

- Lichtgrenze on Vimeo

- A collection of stories from Berliners who Remember the Fall of the Wall and Berlin 1963: three stories of a divided city.

- Timoth Garton Ash’s article about The fall of the Berlin Wall – What it meant to be there

- Reuters photo slideshow – When Berlin Was Two.

- Deutsche Welle Opinion Piece – November 9th 1989: An unforgettable day for Germany, and for Europe.

- 25 years on – different international perspectives about what caused the fall of the wall.

#

Pavement markers showing the route of the former division still run through Berlin today. Photo © Kelly Hignett.The Race Against the Stasi [Book Review]

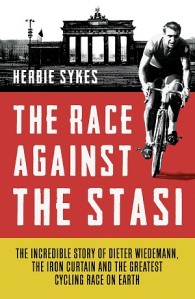

BOOK REVIEW: Herbie Sykes, The Race Against the Stasi: The Incredible Story of Dieter Wiedemann, the Iron Curtain and the Greatest Cycling Race on Earth. (Aurum Press, 2014).

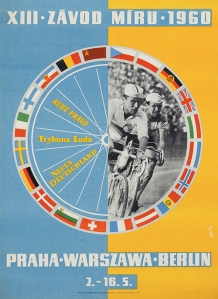

The Race Against the Stasi tells the story of Dieter Wiedemann, a small town boy with a love of cycling, who became one of East Germany’s sporting elite. In 1962, he was even chosen to represent the GDR in the annual Peace Race, the ‘Tour de France of the East’ and the biggest event in the sporting calendar for cycling enthusiasts in the Eastern bloc. During the summer of 1960 however, Dieter Wiedemann fell in love with Sylvia Hermann, a girl from the Western zone of Germany who was visiting relatives in Dieter’s home town of Floha. After Sylvia returned home, the two wrote to one another regularly, a correspondence that they maintained after the closure of the inner-Berlin border in August 1961. (“You assumed it was a temporary thing” said Dieter, when discussing his reaction to the construction of the Berlin Wall “The feeling was that the politicians would sort it out somehow, and that things would just go back to normal”).

As time passed, the division of Germany assumed more permanence, travel between East and West became more restrictive and it became increasingly clear that Dieter and Sylvia could not be together unless one of them was prepared to ‘switch sides’. So in 1964, when Dieter was sent to participate in a cycling qualification race taking place in Giessen, a town in West Germany not far from where Sylvia and her family lived, he began plotting his escape. On 4th July 1964, he took advantage of a break in training one afternoon to ‘take his bike out for a ride’, and never returned. Dieter was granted asylum in the FRG and started a new life there; gaining a professional contract to ride for the West German cycling team ‘Torpedo’, and even competing in the Tour de France in 1967. Dieter and Sylvia married, and raised three children together. Fifty years on, Herbie Sykes tells the story of Dieter Wiedemann for the very first time, drawing on a potent combination of personal testimonies and archival research.

While the love story between Dieter and Sylvia lies at the heart of this tale, it would be wrong to dismiss this as merely a Cold War romance; a pair of star-crossed lovers, separated by the ‘iron curtain’. The Race Against the Stasi also provides some fascinating insights into life in the GDR. Wiedemann’s story highlights the politicisation of sport in East Germany; sporting success was hijacked as propaganda, used to create popular patriotism within the GDR and raise the regime’s prestige overseas, with the sporting elite viewed as ‘diplomats in tracksuits’. Full-time sportsmen benefitted from generous state funding and enjoyed a privileged status, including the opportunity to travel overseas to compete. Sporting success bought material benefits and a certain amount of political influence, as shown by Dieter’s intervention to ensure that Sylvia was granted a rare travel permit for a second visit to Floha in 1964. However, poor sporting performance could also attract political pressure, as Dieter discovered when the GDR teams’ third place finish in the 1962 Peace Race was deemed ‘unsatisfactory’, bringing him to the attention of the Stasi who were ‘looking for someone to blame’.

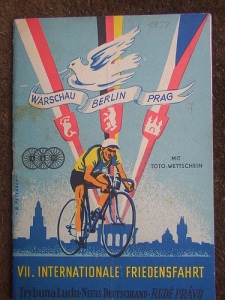

A poster advertising the 1954 Peace Race – an annual stage cycling race known as ‘the Tour de France of the East’.

While Dieter’s relationship with Sylvia was clearly the biggest catalyst for his decision to defect to the West, HE also outlines his growing frustration and resentment with the politicisation, oppression and tightening of social control following the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the more restrictive aspects of life in communist East Germany. In The Race Against the Stasi Dieter describes how, after 1961, his refusal to join the Communist Party led to questions being asked about his lack of ‘ideological loyalty’ to the regime, which begin to have an adverse effect on his sporting career:

“I just wanted to be able to race my bike, and to feel like I had the same chance as everybody else. Now it really dawned on me that I didn’t and probably never would have … I wasn’t political at all, but nor did I want my life to become politicised … the country was getting more and more oppressive. There were more police, more people being arrested and more Stasi” (Dieter Wiedemann, quoted in The Race Against the Stasi, pp168-173)

The Race Against the Stasi is structured around the different ‘lives’ of Dieter Wiedemann – his life in the GDR up until 1964, His ‘second life’ in the FRG following his defection, and his ‘third life’ as represented through reports and documents taken from Wiedemann’s Stasi file, which only became available after the collapse of communism and the reunification of Germany. Personal testimonies feature heavily throughout The Race Against the Stasi, as in addition to the inclusion of detailed narratives from Dieter and Sylvia, Sykes has collected testimonies from a range of other individuals who are connected to the story. Throughout the book the various narrators are allowed to ‘speak for themselves’, and Sykes’ own ‘voice’ (as author/interviewer) is almost entirely absent, limited to a short introduction and a few concluding comments. This is a very effective narrative trope, and the inclusion of multiple supporting narratives generally works very well (for example, the dual narrative between Dieter and Sylvia, describing their first meeting was a particularly nice touch) although there are also a few places where the rather frequent jump between multiple narrators is a little frustrating.

Sykes has also carried out painstaking archival research, as illustrated by the many documents interspersed throughout the narrative, including relevant press reports from Neues Deutschland and other media, multiple copies of confidential reports compiled by the Stasi, copies of some of the letters Dieter had written to Sylvia 1960-1964 (none of Sylvia’s letters to Dieter have survived as they were destroyed by his family after he left), and personal photographs of the couple and their families. The inclusion of so many sources interspersed throughout the book is a great addition, providing some wonderful insights, although at times the sheer volume of sources included does break-up the narrative flow. The extracts from Dieter’s Stasi file provide a great snapshot of the high levels of surveillance and social control that existed in the GDR, but also illustrate that errors and oversights were still possible – given their interest in Dieter, it seemed almost unbelievable that the Stasi remained largely unaware of the close relationship he had formed with Sylvia until after his defection, even with their frequent exchange of letters 1960-64 and Dieter’s personal intervention to request a permit to allow Sylvia to visit him shortly before his defection.

A photo of Dieter Wiedemann during his Torpedo racing days. Photo Source: http://www.siteducyclisme.net/coureurfiche.php?coureurid=27942

Finally, Sykes does not shy away from highlighting the damage that Dieter’s decision to leave the GDR caused for those he left behind. While Dieter and Sylvia got their ‘happy ending’, his family suffered terribly – not only had they lost Dieter, but they were subjected to close Stasi surveillance and endured numerous socio-economic sanctions (Dieter’s father lost his job and his younger brother, Eberhard, also a talented cyclist, was prevented from ever racing professionally). Ultimately, their family relationship was fractured beyond repair:

“Looking back, I suppose we were all victims … and no relationship could survive all that without being seriously compromised” (Dieter, quoted in The Race Against the Stasi, p386)

“At times, at the start, it felt like my whole life was a fight between East and West” (Sylvia, quoted in The Race Against the Stasi, p318)

The story of Dieter Wiedemann is an intriuging tale, encompassing a potent combination of politics, sport, love and betrayal. Herbie Sykes impresively balances the political and the personal, making The Race Against the Stasi an enjoyable, compelling and highly recommended read.

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS