Women and Repression in Communist Czechoslovakia

Today’s blog post, written for International Women’s Day 2016, relates to my current research into women’s experiences of repression in communist Eastern Europe, with a particular focus on Czechoslovakia 1948-1968, during the period of Stalinist terror and its immediate aftermath.

The vast majority of the 90,000 – 100,000 Czechoslovak citizens who were prosecuted and interned for political crimes between 1948-1954 were men; only between 5,000 – 9,000 (5-10%) were women. These women were held in numerous different prisons and forced labour camps across Czechoslovakia, where they frequently experienced poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene and medical care and enforced labour, while enduring physical and psychological violence, abuse and humiliation at the hands of the penal authorities. Beyond this, however, hundreds of thousands of other Czechoslovakian women also became ‘collateral’ victims of state-sanctioned repression during these years. The Czechoslovakian Communist Party actively pursued a policy of ‘punishment through kinship ties’, so while family members of those incarcerated for political crimes were not necessarily arrested themselves, they were considered ‘guilty by association’. As men comprised the majority of political prisoners, it was usually the women who were left trying to hold their families together and survive in the face of sustained political and socio-economic discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

The growth in published memoirs and oral history projects such as Paměť Národa and Političtívězni.cz in post-communist Czech Republic and Slovakia have encouraged more victims of repression to record their stories. However, women’s experiences of political repression in communist Czechoslovakia remain under-researched and under-represented in the historiography. It is often suggested that women are generally more reluctant to share personal accounts of traumatic experiences, in comparison with their male counterparts. For example Historian Tomáš Bursík’s study of Czechoslovakian women prisoners Ztratili jsme mnoho casu … Ale ne sebe! notes that in many cases ‘Women do not like to return to their suffering, that misfortune they affected, the humiliation that followed. They do not want to talk about it’. In her own account of imprisonment in communist Czechoslovakia, Krásná němá paní, Božena Kuklová-Jíšová also explained that:

‘We women are very often criticized for not writing about ourselves, about our fate. Perhaps it is because there were some moments which were very humiliating for us; or because in comparison to the many different brave acts of men, our acts seem so narrow-minded. But the main reason is that we have difficulties presenting ourselves to the world’.

This reticence extends to many women who experienced collateral or secondary repression, such as Jo Langer, who despite being subjected to sustained political harassment and socio-economic discrimination including loss of employment and forced relocation when her husband Oscar was arrested and interned 1951-1960, described how, upon receiving the first full account of her husband’s traumatic experiences in the camps after his release, she felt ‘shattered and deeply ashamed of having thought myself a victim of suffering’ (You can read more about Jo Langer’s autobiography Convictions: My Life with a Good Communist in my previous blog post HERE)

However, the inclusion of women’s narratives make an important contribution to the historiography, broadening and deepening our understanding of terror and repression in communist Eastern Europe. A number of women who endured political repression have shared their stories, which not only document their suffering at the hands of the Communist Party but are also testimony to their strength, resistance and will to survive. Through their narratives, these women are able to present themselves simultaneously as both victims and survivors of communist repression.

Today then, it seems fitting to mark International Women’s Day 2016 by briefly highlighting two examples to pay tribute to the many strong, spirited and inspiring women who feature in my own research.

Dagmar Šimková

“The screeching seagulls are flying around me. I am so free, I can walk barefoot. And the waves wash away traces of my steps long before a print could be left”.

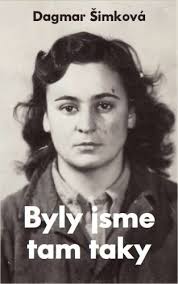

Dagmar Simkova’s arrest, official photograph (1952). Source: http://zpravy.idnes.cz/autorka-svedectvi-o-zenskych-veznicich-krasna-a-inteligentni-dagmar-simkova-by-se-dozila-80-let-i1u-/zpr_archiv.aspx?c=A090522_114346_kavarna_bos

Dagmar Šimková’s autobiographical account of her experiences in prison Byly jsme tam taky [We were there too] is arguably one of the strongest testimonies of communist-era imprisonment to emerge from the former east bloc. Šimková’s family became targets after the communist coup of 1948 due to their ‘bourgeois origins’ (her father had been a banker). Their villa was confiscated by the Communists, while Dagmar and her sister Marta were denied access to university. While Marta fled Czechoslovakia in 1950, Dagmar became involved in resistance activities, printing and distributing anti-communist leaflets and posters mocking the new Czechoslovakian leader, Klement Gottwald. In October 1952, following a failed attempt to help two friends avoid military service by escaping to the West, she was arrested, aged 23, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Between 1952 – 1966 Šimková passed through various prisons and labour camps in Czechoslovakia: in Prague, Pisek, Ceske Budejovice and Opava. In 1955 she even briefly escaped from Želiezovce, a notoriously harsh agricultural labour camp in Slovakia. Sadly, her freedom was shortlived: she was found sleeping in a haystack at a nearby farm two days later, recaptured and returned to Želiezovce, where an additional three years was added to her existing prison term as a punishment.

Dagmar Simkova’s book Byly Jsme Tam Taky [“We Were There Too”]

From 1953, Šimková was held in Pardubice Prison near Prague, in the women’s department ‘Hrad’ (Castle), which was specially created to house 64 women who were perceived as being the ‘most dangerous’ political prisoners, and segregate them from the main prison population. Here, Šimková participated in several organised hunger strikes to demand better conditions for women prisoners. She was also an active participant in the ‘prison university’ founded by former university professor Růžena Vacková, who gave secret lectures on fine art, literature and languages to her fellow prisoners. Šimková later described how ‘We devoured every word. We tried to remember, and understand, like the best students at universities’. Some of the women even managed to compile some lecture notes into a small book which was secretly hidden, before being smuggled out of Pardubice in 1965. This book is currently held in the Charles University archives.

After a total of fourteen years incarceration, Dagmar Šimková was finally released in April 1966, aged 37. Two years later, during the liberalisation of the Prague Spring in 1968 she was instrumental in establishing K 231, the first organisation to represent former political prisoners in Czechoslovakia. Following the Soviet invasion to halt the Czechoslovak reforms, Šimková emigrated to start a new life in Austrialia, where she completed two University degrees, worked as an artist, prison therapist and even trained as a stuntwoman! She also worked with Amnesty International , continuing to campaign for better prison conditions until her death in 1995.

Heda Margolius Kovály

Heda Margolius Kovaly. Source: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/dec/13/heda-margolius-kovaly

Heda Margolius Kovály’s memoir, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 remains one of the most damning accounts of the violence and repression that characterised mid-twentieth century central and eastern Europe. Heda’s incredible life story spans the Nazi concentration camps, the devastation of WWII, the communist coup and the post-war Stalinist terror in Czechsolovakia. Having survived Auschwitz, Heda escaped during a death march to Bergen-Belsen and managed to make her way home to Prague. After the war, she was reunited with her husband Rudolf Margolius, who was also a concentration camp survivor, and a committed communist. Following the Communist coup of February 1948, Rudolf served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, only to quickly fall victim to the Stalinist purges. Rudolf was arrested on 10 January 1952, brutally interrogated and forced to falsely confess to a range of ‘crimes’ including sabotage, espionage and treason. He was subsequently convicted as a member of the alleged ‘anti-state conspiracy’ group led by former General Secretary, Rudolf Slansky, in Czechoslovakia’s most infamous show trial. In December 1952, Rudolf was executed, along with 10 of his co-defendents.

Following Rudolf’s arrest, Heda described how ‘Suddenly, the world tilted and I felt myself falling … into a bottomless space’ . She was left to raise their young son, Ivan, while fighting to survive in the face of sustained state-sanctioned repression. She was swiftly fired from her job at a publishing house, and was forced to work extremely long hours for pitifully little pay, while living on ‘bread and milk’ in order to make enough to cover their basic needs. Her savings and most of her possessions were confiscated, and she and Ivan were forced to leave their home and move to a single room in a dirty and dilapidated apartment block on the outskirts of Prague, where it was so cold that ice formed inside during the winter months, and cockroaches ‘almost as large as mice’ crawled up the walls. Abandoned by most of her former friends, Heda describes how she became a social pariah who was treated ‘like a leper’. At best, former friends and acquaintances would ignore her when they passed in the street, while others would ‘stop and stare with venom’ sometimes even spitting at her as she walked by.

The strain of living under these conditions caused Heda to become critically ill, but she was initially denied medical treatment. When she was finally admitted to hospital she had a temperature of 104 and a long list of ailments, leading the doctor who treated her to compare her to a newly released concentration camp survivor. It was while she was recovering in hospital that she heard Rudolf’s trial testimony broadcast on the radio, and she listened to her husband monotonously admit to ‘lie after lie’ as he recited the script he had been forced to learn. Forcibly discharged from hospital before she was fully recovered, Heda was so weak that she had to crawl ‘inch by inch’ from the front door of her apartment block to her bedroom, where she spent several weeks following Rudolf’s execution ‘motionless, without a thought, without pain, in total emptiness … lying in my bed as if it were a coffin’.

‘Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968’ is Heda Margolius Kovaly’s account of surviving Nazi and Communist persecution.

Nevertheless, Heda regained her strength. Her son Ivan later described how, even in the face of sustained persecution ‘Heda survived through her determination and managed to look after us both’. She continued to maintain Rudolf’s innocence and fought to clear his name, writing endless letters and attempting to arrange meetings with various communist officials, most of whom refused to see her. Following Rudolf’s execution, she dared to publicly mourn him by dressing completely in black, in a deliberate challenge to the Communist Party. After she remarried in 1955, she continued to campaign for Rudolf’s full rehabilitation. In April 1963, she was finally summoned to the Central Committee where Rudolf’s innocence was privately confirmed, and Heda was asked to write a ‘summary of losses’ suffered as a result of his arrest and conviction, so that she could apply for compensation. In Under a Cruel Star, she described how:

‘I sat down at my typewriter and typed up a list:

– Loss of Father

– Loss of Husband

– Loss of Honour

– Loss of Health

– Loss of Employment and Opportunity to Complete Education

– Loss of Faith in the Party and JusticeOnly at the end did I write:

– Loss of Property’.

Upon presentation of this list, the Communist officials responded in confusion:

‘”But you must understand that no one can make these losses up to you?”. “Exactly” I said “That’s why I wrote them up for you, So that you know that whatever you do you can never undo what you have done … you murdered my husband. You threw me out of every job I had. You had me thrown out of a hospital! You threw us out of our apartment and into a hovel where only by some miracle we did not die. You ruined my son’s childhood! And now you think you can compensate for that with a few crowns? Buy me off? Keep me quiet?”.’

Following the failed Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Heda left Czechoslovakia and settled in the USA with her second husband, Pavel Kovály. There, she continued to forge a successful career as a translator in addition to working as a librarian in the international law library at Harvard University. Heda Margolius Kovály died in 2010, aged 91. In addition to her personal memoir Under A Cruel Star, an English-language translation of Heda’s novel Nevina [Innocence] was recently published in 2015 – which I can also highly recommend!

Convictions: Life in Communist Czechoslovakia

“Whatever the price in human lives, for all of its murderous record, socialism has killed more souls and minds than bodies” – Jo Langer.

I recently read Convictions: My Life With A Good Communist, Jo Langer’s account of life in Czechoslovakia spanning the decades between the initial establishment of communism in 1948 and the failed Prague Spring of 1968. First published in 1979, and re-issued by Granta earlier this year (with an introduction written by Neil Ascherson), playwright Tom Stoppard recently described Convictions as ‘one of the classic testimonies to come out of post-war Europe under communist rule’.

Jo moved from her home in Budapest to Bratislava when she married committed Slovakian communist Oscar Langer in 1934. The couple, both Jewish, fled to America in 1938 where they remained for the duration of the Second World War (while numerous members of their families who remained behind perished in the Holocaust), before returning to Czechoslovakia to assist with the construction of a new socialist state and society. Oscar, working as an economist for the Central Committee, quickly rose to prominence within the Czechoslovakian Communist Party, while Jo worked for State Exports in Bratislava. However, everything changed when Oscar fell victim to the purges and show trials of the early 1950s.

The Stalinist-era terror and the political purges that swept communist Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War are thus a central part of Jo’s story and Convictions joins a growing list of memoirs penned by those who were affected by these turbulent years. In 1951 Oscar Langer (the ‘good communist’ of her book’s title) was arrested, detained and forced to give (false) evidence in the infamous Slansky trial of 1952; before being sentenced to a 22 year prison term himself, for charges including espionage, sabotage, high treason and ‘Zionist conspiracy’. Several of the Langers’ communist party acquaintances were also purged and either executed or imprisoned. While similar show trials occurred across much of Eastern Europe in this period the Czechoslovakian purges were distinguished by their underlying anti-semitism: a high number of Jews were targeted and 11 of the 14 defendants in the Slansky trial were Jewish, charged with participation in an alleged ‘Zionist conspiracy’ to undermine and overthrow communism.

In Convictions Jo vividly describes the slowly creeping climate of fear that came to dominate their lives during the period of the purges: initially both Oscar and Jo attempted to ascribe the arrests of loyal communists (many of whom were also personal friends) to ‘over zealousness’ on the part of the investigators. As it became apparent that Oscar himself was under surveillance their sense of unease and helplessness grew, but even when Jo finally received news of Oscar’s arrest she still hoped that something could be done to clarify his innocence and secure his speedy release so that justice could prevail. However, as Jo comes to realise when she meets sustained official resistance to any kind of enquiry or investigation into Oscar’s case: ‘the show trials were the house of cards on which the whole power system rested and if anyone started tampering with even one small part of the structure, the whole thing would collapse’.

For much of the book, Oscar Langer is absent – the first few years of his long incarceration are spent mining uranium in a north Bohemian labour camp – but his absence assumes a dominant presence throughout Jo’s narrative. As Jo’s own story unfolds, we also receive insights into Oscar’s ordeal. In a letter smuggled out from his prison cell and partly reproduced by Jo here, Oscar provides a detailed first-hand account of the circumstances surrounding his arrest, detention, trial and imprisonment. In his letter, Oscar proclaimed his innocence, retracted his confession and detailed how his experiences at the hands of the communist security agents ‘bought me into a state of mind that cannot be considered that of a normally thinking sane man’. Oscar describes how he resisted in the face of the ‘combination of terror, deceit, provocation, blackmail and alternate physical and mental torture’ used by the secret police to extract confessions – constant interrogation, sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, agent provocateurs, exposure to cold and hunger, regular beatings, humiliation and threats made against his family – before (after two failed suicide attempts) finally submitting to make a full ‘confession’. His signed testimony (which was dictated to him by his interrogators and which he was later forced to read verbatim at the Slansky trial) made absurd and easily refutable admissions about his involvement in an

anti-communist conspiracy with men he had never even met. During the Slansky trial, Oscar’s testimony was broadcast over the radio and his confession was printed in the press; so Jo was also able to discredit many of his claims.

Convictions focuses predominantly on the personal – recalling one woman’s struggle to survive in a repressive, flawed and unforgiving system. When Oscar was arrested Jo not only lost her husband but also her privileged place in society (becoming a ‘non-person’) and the last shreds of faith in the communist system she had found it increasingly hard to believe in. Forcibly evicted from her home and dismissed from her job as a result of Oscar’s ‘crimes’, Jo and her two young daughters were exiled to a remote countryside village, where she managed to survive by taking on occasional translation work and depending on the kindness of strangers. In Jo’s own words, ‘life had become what it was and people had to make the best of it’.

There are insights too, into a variety of personal relationships – her own troubled relationship with Oscar (despite his ordeal, he remained a committed communist until the end of his life); with her two daughters, and with various other friends, neighbours and acquaintances including the forging of some unlikely friendships, as people found themselves bought together due to the circumstances of the time. When Jo first turns to the people she thought she could depend on for help, many of them shun her (often through fear of implicating themselves, due to a desperate desire for self-preservation), but contrasted with this are occasional unexpected and spontaneous acts of genuine kindness from both friends and strangers – such as Bronia, a casual acquaintance who brings Jo food on the evening she is evicted from her flat and forcibly ‘resettled’ and Maria, the café owner who shelters Jo and her younger daughter Tania when they are caught out in a snowstorm.

However, Jo’s personal story effectively intersects with the bigger picture as she navigates the changing political climate in Czechoslovakia 1948-1968. Jo analyses the early attempts to establish socialism in Czechoslovakia through the reorganisation of politics, economics, society and culture; effectively details the Hobbesian climate of the purges and trials of the late 1940s and early 1950s and explores the impact of Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s subsequent policy of Destalinisation (noting that the effects of Stalin’s death took longer to be felt in Czechoslovakia compared with elsewhere in the Eastern bloc, Jo describes how she felt the first real influence of the post-Stalinist ‘thaw’ during a rare prison visit to Oscar at the end of the 1950s, because for the first time ‘there was no wire dividing them’). Jo describes her sadness over the Soviet invasion of her native Hungary in 1956, during which time she monitered events closely as she was employed to interpret communications coming into Bratislava from Budapest via telex. Of course, Czechoslovakia would have its own ‘Hungary’ 12 years later: the failed Prague Spring and Soviet-led invasion of August 1968, which provided Jo with the opportunity to flee Czechoslovakia. She devotes some time to briefly assessing the events of 1968 too, noting the mixture of popular optimism inspired by the rise of Alexander Dubcek (she wishes her husband had lived to see the attempts to develop ‘socialism with a human face’ in Czechoslovakia) mixed with what would prove to be well-founded cynicism about the ability of communism to reform itself.

Oscar Langer was eventually released from prison and rehabilitated in the early 1960s. However, his return was not the happy homecoming that Jo had yearned for. Their marriage had never been trouble-free, but while she remained loyal to Oscar during his incarceration and never doubted his innocence, the long years of limited and censored correspondence and occasional snatched prison visits had taken their toll. She describes poignantly the true impact her husband’s return had on the family after so many years of living without him: the sudden reappearance of a dominant father figure who was a virtual stranger to her two daughters (for the oldest, Susie, he was a distant childhood memory, while the youngest, Tania, only ever remembered seeing him through prison wire), and on her own life. Both Oscar and Jo were left battling their own private demons as a result of their mistreatment by the regime they had striven to support (Jo tellingly concludes that ‘whatever the price in human lives, for all of its murderous record, socialism has killed more souls and minds than bodies’) but while Jo became thoroughly disillusioned and hardened by the reality of life in communist Czechoslovakia, Oscar continued to cling to his ideological ideals, choosing to view his arrest and imprisonment as a ‘dreadful but exceptional mistake’ in an otherwise normally functioning state, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Their time together was brief: Oscar was left physically weakened after years of hard labour during his incarceration and

died after a short illness following his release from prison.

Jo Langer fled Czechoslovakia in the aftermath of the Prague Spring in 1968, and finally settled in Sweden, where she died in 1990. Her story is a remarkable tale of courage, survival and endurance; she vividly demonstrates the devastating impact of the Stalinist era terror, both physically and psychologically, on those directly involved (such as Oscar) and on numerous ‘secondary casulaties’, those deemed ‘guilty by association’ such as herself and her daughters. The personal experiences of everyday life effectively intersect with the high politics of the time, and as a result Jo’s depiction of her life in communist Czechoslovakia provides numerous insights into the experiences of life in a hostile state. This is a story about losing – and gaining – ones convictions in the face of adversity. I would recommend Convictions to anyone interested in communist Eastern Europe and will certainly be including it on the recommended reading list for students taking my own course on Eastern Europe at Swansea this year.

You can purchase Convictions via Amazon HERE.

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS