Women and Repression in Communist Czechoslovakia

Today’s blog post, written for International Women’s Day 2016, relates to my current research into women’s experiences of repression in communist Eastern Europe, with a particular focus on Czechoslovakia 1948-1968, during the period of Stalinist terror and its immediate aftermath.

The vast majority of the 90,000 – 100,000 Czechoslovak citizens who were prosecuted and interned for political crimes between 1948-1954 were men; only between 5,000 – 9,000 (5-10%) were women. These women were held in numerous different prisons and forced labour camps across Czechoslovakia, where they frequently experienced poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene and medical care and enforced labour, while enduring physical and psychological violence, abuse and humiliation at the hands of the penal authorities. Beyond this, however, hundreds of thousands of other Czechoslovakian women also became ‘collateral’ victims of state-sanctioned repression during these years. The Czechoslovakian Communist Party actively pursued a policy of ‘punishment through kinship ties’, so while family members of those incarcerated for political crimes were not necessarily arrested themselves, they were considered ‘guilty by association’. As men comprised the majority of political prisoners, it was usually the women who were left trying to hold their families together and survive in the face of sustained political and socio-economic discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

The growth in published memoirs and oral history projects such as Paměť Národa and Političtívězni.cz in post-communist Czech Republic and Slovakia have encouraged more victims of repression to record their stories. However, women’s experiences of political repression in communist Czechoslovakia remain under-researched and under-represented in the historiography. It is often suggested that women are generally more reluctant to share personal accounts of traumatic experiences, in comparison with their male counterparts. For example Historian Tomáš Bursík’s study of Czechoslovakian women prisoners Ztratili jsme mnoho casu … Ale ne sebe! notes that in many cases ‘Women do not like to return to their suffering, that misfortune they affected, the humiliation that followed. They do not want to talk about it’. In her own account of imprisonment in communist Czechoslovakia, Krásná němá paní, Božena Kuklová-Jíšová also explained that:

‘We women are very often criticized for not writing about ourselves, about our fate. Perhaps it is because there were some moments which were very humiliating for us; or because in comparison to the many different brave acts of men, our acts seem so narrow-minded. But the main reason is that we have difficulties presenting ourselves to the world’.

This reticence extends to many women who experienced collateral or secondary repression, such as Jo Langer, who despite being subjected to sustained political harassment and socio-economic discrimination including loss of employment and forced relocation when her husband Oscar was arrested and interned 1951-1960, described how, upon receiving the first full account of her husband’s traumatic experiences in the camps after his release, she felt ‘shattered and deeply ashamed of having thought myself a victim of suffering’ (You can read more about Jo Langer’s autobiography Convictions: My Life with a Good Communist in my previous blog post HERE)

However, the inclusion of women’s narratives make an important contribution to the historiography, broadening and deepening our understanding of terror and repression in communist Eastern Europe. A number of women who endured political repression have shared their stories, which not only document their suffering at the hands of the Communist Party but are also testimony to their strength, resistance and will to survive. Through their narratives, these women are able to present themselves simultaneously as both victims and survivors of communist repression.

Today then, it seems fitting to mark International Women’s Day 2016 by briefly highlighting two examples to pay tribute to the many strong, spirited and inspiring women who feature in my own research.

Dagmar Šimková

“The screeching seagulls are flying around me. I am so free, I can walk barefoot. And the waves wash away traces of my steps long before a print could be left”.

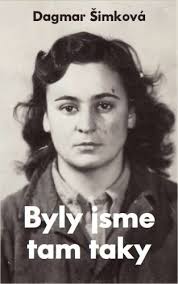

Dagmar Simkova’s arrest, official photograph (1952). Source: http://zpravy.idnes.cz/autorka-svedectvi-o-zenskych-veznicich-krasna-a-inteligentni-dagmar-simkova-by-se-dozila-80-let-i1u-/zpr_archiv.aspx?c=A090522_114346_kavarna_bos

Dagmar Šimková’s autobiographical account of her experiences in prison Byly jsme tam taky [We were there too] is arguably one of the strongest testimonies of communist-era imprisonment to emerge from the former east bloc. Šimková’s family became targets after the communist coup of 1948 due to their ‘bourgeois origins’ (her father had been a banker). Their villa was confiscated by the Communists, while Dagmar and her sister Marta were denied access to university. While Marta fled Czechoslovakia in 1950, Dagmar became involved in resistance activities, printing and distributing anti-communist leaflets and posters mocking the new Czechoslovakian leader, Klement Gottwald. In October 1952, following a failed attempt to help two friends avoid military service by escaping to the West, she was arrested, aged 23, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Between 1952 – 1966 Šimková passed through various prisons and labour camps in Czechoslovakia: in Prague, Pisek, Ceske Budejovice and Opava. In 1955 she even briefly escaped from Želiezovce, a notoriously harsh agricultural labour camp in Slovakia. Sadly, her freedom was shortlived: she was found sleeping in a haystack at a nearby farm two days later, recaptured and returned to Želiezovce, where an additional three years was added to her existing prison term as a punishment.

Dagmar Simkova’s book Byly Jsme Tam Taky [“We Were There Too”]

From 1953, Šimková was held in Pardubice Prison near Prague, in the women’s department ‘Hrad’ (Castle), which was specially created to house 64 women who were perceived as being the ‘most dangerous’ political prisoners, and segregate them from the main prison population. Here, Šimková participated in several organised hunger strikes to demand better conditions for women prisoners. She was also an active participant in the ‘prison university’ founded by former university professor Růžena Vacková, who gave secret lectures on fine art, literature and languages to her fellow prisoners. Šimková later described how ‘We devoured every word. We tried to remember, and understand, like the best students at universities’. Some of the women even managed to compile some lecture notes into a small book which was secretly hidden, before being smuggled out of Pardubice in 1965. This book is currently held in the Charles University archives.

After a total of fourteen years incarceration, Dagmar Šimková was finally released in April 1966, aged 37. Two years later, during the liberalisation of the Prague Spring in 1968 she was instrumental in establishing K 231, the first organisation to represent former political prisoners in Czechoslovakia. Following the Soviet invasion to halt the Czechoslovak reforms, Šimková emigrated to start a new life in Austrialia, where she completed two University degrees, worked as an artist, prison therapist and even trained as a stuntwoman! She also worked with Amnesty International , continuing to campaign for better prison conditions until her death in 1995.

Heda Margolius Kovály

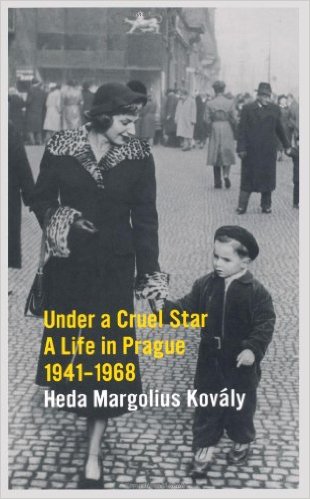

Heda Margolius Kovaly. Source: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/dec/13/heda-margolius-kovaly

Heda Margolius Kovály’s memoir, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 remains one of the most damning accounts of the violence and repression that characterised mid-twentieth century central and eastern Europe. Heda’s incredible life story spans the Nazi concentration camps, the devastation of WWII, the communist coup and the post-war Stalinist terror in Czechsolovakia. Having survived Auschwitz, Heda escaped during a death march to Bergen-Belsen and managed to make her way home to Prague. After the war, she was reunited with her husband Rudolf Margolius, who was also a concentration camp survivor, and a committed communist. Following the Communist coup of February 1948, Rudolf served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, only to quickly fall victim to the Stalinist purges. Rudolf was arrested on 10 January 1952, brutally interrogated and forced to falsely confess to a range of ‘crimes’ including sabotage, espionage and treason. He was subsequently convicted as a member of the alleged ‘anti-state conspiracy’ group led by former General Secretary, Rudolf Slansky, in Czechoslovakia’s most infamous show trial. In December 1952, Rudolf was executed, along with 10 of his co-defendents.

Following Rudolf’s arrest, Heda described how ‘Suddenly, the world tilted and I felt myself falling … into a bottomless space’ . She was left to raise their young son, Ivan, while fighting to survive in the face of sustained state-sanctioned repression. She was swiftly fired from her job at a publishing house, and was forced to work extremely long hours for pitifully little pay, while living on ‘bread and milk’ in order to make enough to cover their basic needs. Her savings and most of her possessions were confiscated, and she and Ivan were forced to leave their home and move to a single room in a dirty and dilapidated apartment block on the outskirts of Prague, where it was so cold that ice formed inside during the winter months, and cockroaches ‘almost as large as mice’ crawled up the walls. Abandoned by most of her former friends, Heda describes how she became a social pariah who was treated ‘like a leper’. At best, former friends and acquaintances would ignore her when they passed in the street, while others would ‘stop and stare with venom’ sometimes even spitting at her as she walked by.

The strain of living under these conditions caused Heda to become critically ill, but she was initially denied medical treatment. When she was finally admitted to hospital she had a temperature of 104 and a long list of ailments, leading the doctor who treated her to compare her to a newly released concentration camp survivor. It was while she was recovering in hospital that she heard Rudolf’s trial testimony broadcast on the radio, and she listened to her husband monotonously admit to ‘lie after lie’ as he recited the script he had been forced to learn. Forcibly discharged from hospital before she was fully recovered, Heda was so weak that she had to crawl ‘inch by inch’ from the front door of her apartment block to her bedroom, where she spent several weeks following Rudolf’s execution ‘motionless, without a thought, without pain, in total emptiness … lying in my bed as if it were a coffin’.

‘Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968’ is Heda Margolius Kovaly’s account of surviving Nazi and Communist persecution.

Nevertheless, Heda regained her strength. Her son Ivan later described how, even in the face of sustained persecution ‘Heda survived through her determination and managed to look after us both’. She continued to maintain Rudolf’s innocence and fought to clear his name, writing endless letters and attempting to arrange meetings with various communist officials, most of whom refused to see her. Following Rudolf’s execution, she dared to publicly mourn him by dressing completely in black, in a deliberate challenge to the Communist Party. After she remarried in 1955, she continued to campaign for Rudolf’s full rehabilitation. In April 1963, she was finally summoned to the Central Committee where Rudolf’s innocence was privately confirmed, and Heda was asked to write a ‘summary of losses’ suffered as a result of his arrest and conviction, so that she could apply for compensation. In Under a Cruel Star, she described how:

‘I sat down at my typewriter and typed up a list:

– Loss of Father

– Loss of Husband

– Loss of Honour

– Loss of Health

– Loss of Employment and Opportunity to Complete Education

– Loss of Faith in the Party and JusticeOnly at the end did I write:

– Loss of Property’.

Upon presentation of this list, the Communist officials responded in confusion:

‘”But you must understand that no one can make these losses up to you?”. “Exactly” I said “That’s why I wrote them up for you, So that you know that whatever you do you can never undo what you have done … you murdered my husband. You threw me out of every job I had. You had me thrown out of a hospital! You threw us out of our apartment and into a hovel where only by some miracle we did not die. You ruined my son’s childhood! And now you think you can compensate for that with a few crowns? Buy me off? Keep me quiet?”.’

Following the failed Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Heda left Czechoslovakia and settled in the USA with her second husband, Pavel Kovály. There, she continued to forge a successful career as a translator in addition to working as a librarian in the international law library at Harvard University. Heda Margolius Kovály died in 2010, aged 91. In addition to her personal memoir Under A Cruel Star, an English-language translation of Heda’s novel Nevina [Innocence] was recently published in 2015 – which I can also highly recommend!

“A Day in the Life Of…”: Women of the Soviet Gulag

The second in this year’s series of student authored articles considers some key aspects of women’s experiences in the Stalinist Gulag camps. Proportionally, women made up a small but significant percentage of the Gulag population and a rich body of written memoirs and personal testimony from surviving female inmates is available today. In this article Katryna Coak draws on some of these accounts to argue that while women may have been subjected to broadly similar conditions as those experienced by male inmates, there were distinctly gendered aspects to the female Gulag experience, particularly relating to women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood in the camps, which could be both uplifting and traumatic in equal measure.

“A Day in the Life Of…”: Women of the Soviet Gulag.

By Katryna Coak.

During the 1930s, the escalation of Stalinist terror and repression (particularly during the Great Terror of 1936-1939) meant that the population of the Gulag labour camps continued to grow. Anne Applebaum estimates that over 18 million people passed through the Gulag in total, and many women were sent to these labour camps, including large numbers of political prisoners, many of whom were sentenced under Article 58, their only crime being their association as ‘wives of enemies of the people’. However, proportionally their numbers remained relatively small in relation to the male population: for example, Mason estimates that in 1939 women only comprised 8.4 per cent of the total Gulag population, while Anne Applebaum has estimated that in 1942 only around 13% of Gulag inmates were female.[1] Initially many camp commanders were reluctant to accept women, as they believed they were weaker than men, so would take longer to fulfil the work norms set by the Gulag administration. In February 1941 the central camp administration even sent a letter to the NKVD and camp commanders ordering them to accept convoys of women and listing jobs that women could be particularly useful for, such as textiles, wood and metal work and light industry.[2]

However, despite their relatively small numbers and despite the fact that men and women had to endure broadly similar living and working conditions within the camps, women’s experiences of the Gulag were also distinctively different to those of their male counterparts in a number of ways, as depicted by the accounts in numerous female memoirs and personal testimonies.

Camp Life

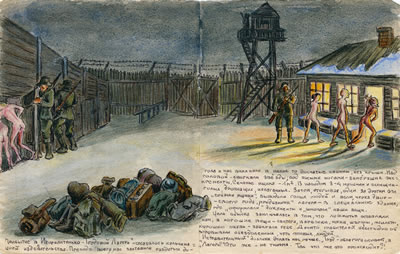

Many women’s first memories of the Gulag tell of their fear, embarrassment and degradation. On arrival at their assigned camp, women were generally led to the bathhouse where they had a rare opportunity to wash. This was often an embarrassing and shocking experience. One former zek recalled how: ‘The personnel were all male. You had to overcome the shame and humiliation, clench your teeth and control yourself, to endure the dirty jokes calmly and not spit at those hideous faces, or punch them between the eyes’.[3] Another former prisoner drew the scene of humiliation, revealing that women were made to wait for their turn naked in the snow:

A drawing by Evfrosiniia Kersnovskaia, a former Gulag prisoner, available via Gulag: Soviet Forced Labour and the Struggle for Freedom: http://gulaghistory.org/nps/onlineexhibit/stalin/women.php

The humiliation did not stop there: guards often exploited the situation to ‘inspect’ the new arrivals, as women were a rarity within the Gulag: ‘After the bath, we had to wait a while for our clothes, which had been taken to be disinfected. This period of waiting was the worst…our guards came in under the pretext that one of us might attempt to escape’ recalled Anna Cieślikowska.[4] The disinfection of prisoner’s clothing was generally ineffective anyway as the water used to wash the clothes was often not hot enough to kill the parasites and merely served to excite them further. In order to reduce the incidence of lice, women therefore endured further embarrassment as their heads and pubis were shaved. This procedure was supposed to be carried out by a female doctor, but they were rarely available, so male guards and doctors gleefully stepped in.

Some women resisted: ‘I was so shocked about it that at first I refused…soldiers kept my hands behind my back, while another forced my legs apart’.[5] But women also had to submit to regular physical searches: ‘They searched our hair, our mouths and even our…[they] were carried out solely to frighten and humiliate us’.[6] This sense of humiliation is also depicted in another drawing by Evfrosiniia Kersnovskaia, illustrating a physical search party, where it is evident that the women are hanging their heads due to the shame and awkwardness of this situation:

A drawing by Evfrosiniia Kersnovskaia, a former Gulag prisoner, depicting a late night search of women, available online via Gulag: Soviet Forced Labour and the Struggle for Freedom: http://gulaghistory.org/nps/onlineexhibit/stalin/women.php

Yet, other women quickly adopted a more pragmatic approach to their new situation. Speaking about the regular physical searches, Elinor Lipper argued that, ‘What we hated worse than the confiscation of the little things we needed, worse than the humiliation of the whole procedure, was the fact that we were robbed of our all-too-brief night’s sleep’ – something which was essential due to the toll taken by the physical labour that all Gulag inmates were subjected to in one form or another.[7] Some women appear to have adjusted to camp life more quickly than others as practical concerns took precedence. Furthermore, other women spoke about how they quickly became more adept at concealing the few personal possessions that they had, utilising fish bones from their daily soup to create needles in order to repair clothing and fashioning knives from bits of metal. Eleanor Lipper, a former Gulag inmate, claimed that ‘women are far more enduring than men…and also more adaptable to unaccustomed physical labour’, while Anne Applebaum has argued that camp women formed more powerful relationships with one another and helped each other in ways male prisoners did not such as by sharing food rations.[8] Kseniia Dmitrievna Medvedskaia also spoke of how she feared ostracism after a stint in the punishment cell, however her apprehensions were quickly dispelled as on her return to the barracks the other women greeted her warmly and shared the food they had saved for her.[9]

Despite this camaraderie however, many women found life in the Gulag to be a demoralising and defeminising experience. Solzhenitsyn commented that due to the toll of regular manual labour in the Gulag, women’s bodies became worn and ‘everything feminine about them ceased to be, both biologically and physically’.[10] Many women also described the shock they felt when they caught a rare glance of their reflections in a broken piece of glass or a mirror. With shaved heads, lose fitting men’s clothing and skeletal bodies, they appeared genderless. Ginzberg described how, while watching another female work brigade: ‘As we continued to watch the files of workers passing by, an inclination of a joke left us. They were indeed sexless…this sight appalled us and took away the last remnants of or courage’.[11] Serving time in the Gulag proved to be a dehumanising experience for many women, many of whom felt they were forcibly stripped of their femininity.

Camp Relationships, Pregnancy and Motherhood

Life in the camps, Anatoly Zhigulin argues, was not all bad: ‘Sometimes people ask me whether there were ever any good times in the camps…of course there were…there were good, even joyful moments that had nothing to do with material comforts’.[12] This comfort could come in the form of a friend or a lover. Sadly, many women were physically abused by male inmates and camp guards, with horrific accounts of rape and abuse a frequent issue in Gulag memoirs. Some women therefore took ‘camp husbands’ to offer them protection, while others deliberately sought out sexual encounters with guards in order to receive physical protection, higher rations and time off work. Elinor Lipper described how ‘women who once dreamed of hearing the phrase “I love you” know found the words “butter, sugar and white bread” a proper substitute’, while another former Gulag inmate explained ‘(‘[I] don’t think that this is the place for love and commitment…I wasn’t in love with Victor. I stayed with him because it isn’t safe for a women to be alone’.[13] However, genuine relationships also formed within the Gulag: In Minlag camp, male and female prisoners sent notes to each other via their friends in the camp hospital. In other camps coded letters were thrown over the fence dividing the two sexes. Some lovers were even ‘married’ across the barbed wire.[14] These relationships could give a prisoner hope in what often seemed to be a hopeless situation.

Pregnancy was therefore a relatively common occurrence in the camps and stories of children and motherhood are a common theme within female memoir literature. Shapalov argues that for many, children symbolised ‘normal’ life and made prisoners feel as though they were on an equal footing with ‘free’ women, something which could have helped some women to regain a sense of femininity and purpose in a hostile environment, [15] while Hava Volovitch spoke of how: ‘our need for love was so desperate that it reached the point of insanity, of banging one’s head against the wall, of suicide. And we wanted a child – the dearest and closest of all people, someone for whom we could give our own life’.[16]

Potentially, there were practical benefits to pregnancy too. A decree of January 10, 1939, stated that female zeks were allowed thirty-five days off work before the birth of their child and twenty-eight after their child was born.[17] Pregnancy could save a woman from beatings and even from execution. Rumours circulated that pregnancy could ensure an early release, as amnesties for pregnant women were implemented at various points. However, pregnancy was seen as a camp offence and many inmates were forced to have abortions, even though the practice was made illegal in the Soviet Union in 1936.[18] Camp officials often took the decision to forcibly terminate a women’s pregnancy so that she could continue to work, in the interests of reaching production targets. There were also some women who attempted to end unwanted pregnancies themselves: Anna Andreevna talks of how she witnessed one woman stabbing herself with needles until she began bleeding heavily, signifying the end of her pregnancy. Even those terminations performed by camp doctors were often unskilled and dangerous.[19] Therefore, pregnancy could be a scary time for expectant mothers.

The survival rate of babies born in the Gulag was extremely low and children were often born in terrible, unhygienic conditions. Hava Volovich retcalled her experience of giving birth to a daughter in the Gulag:

‘She was born in a remote camp barracks, not in the medical block. There were three mothers there, and we were given a tiny room to ourselves…bedbugs poured from the ceiling and walls; we spent the whole night brushing them off the child. During the day we had to go to work and leave the infants with any old woman…these women would calmly help themselves to the food we left for the children’.[20]

Children were not allowed to stay with their mother for long: after the birth they were quickly transferred to a camp nursery and the mothers were sent to a camp for mamki (nursing mothers). Despite ‘official’ camp regulations Mamki were often forced to return to work almost immediately after giving birth, and were only allowed to breast feed their babies at specific times. Mothers were only permitted to visit their children regularly if they were breast-feeding so sometimes camp commanders would claim that a mother had stopped lactating in order to get them back to work earlier. If a woman missed their feeding ‘appointment’, their child would generally go hungry.

The high infant mortality rate in the camps is therefore understandable. Giuli Fedorovna Tsivirko recalls her experience of being a mother in the Gulag: ‘my son died after eight months. He died. He was born weighing one and a half kilograms, blue. He looked at me with the eyes of a grown person. I felt that he was doomed’ And Hava Volovich watched her child slowly turn into ‘a pale ghost with blue shadows under her eyes and sores all over her lips’.[21]

If a child did survive, they would be removed from the camps within two years. This operation was usually carried out at night to take the mothers by surprise and to avoid emotional displays: ‘Then came the order to take the children away from their mothers and send them to a nursery away from Solovki. We were heartbroken! There were so many tears!’ recalls Anna Petrovna Zborovskaia.[22] On discovering that their children had been taken, many women would fling themselves against the barbed wire in an attempt to take their own lives. Once removed from the camp, the address of a child’s whereabouts was usually omitted from the mother’s records making it almost impossible for a mother to trace her child even after she was released.

Not all women in the Gulag camps embraced motherhood: Solzhenitsyn has claimed that some women used pregnancy to ensure early liberation from the Gulag and once freed, they would leave their children on the nearest porch or train station bench, as they no longer had any need for them.[23] However in their memoirs, many female zeks appear to have viewed their children as a humanising force in a dehumanising situation and a way of reclaiming their identity. The birth of a child could will a woman to survive for the child’s sake. However, these children were unlikely to survive, and if they did, ultimately they would be forcibly taken from their mothers. So pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood within the camps could also be an extremely traumatic experience that had the potential to leave both physical and psychological scars.

About the Author:

Katryna Coak has just completed her BA in History at Swansea University. During her final year of study, Katryna specialised in the study of communist Eastern Europe and also researched and wrote her History dissertation about the experiences of Women in the Stalinist-era Gulag camps. Katryna will commence postgraduate study at the University of East Anglia in September 2012.

[1] Emma Mason, ‘Women in the Gulag in the 1930s,’ in Illič, Melanie, ed., Women in the Stalin Era, (Palgrave: 2001); Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History, (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 287

[2] Anne Applebaum, Ibid, 287

[3] Anna Cieślikowska, ‘Fragments,’ reproduced in Jehanne Gheith and Katherine Jolluck, Gulag Voices: Oral Histories of Soviet Incarceration and Exile, Palgrave Macmilian: 2011).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Michael Solomon, Magadan, (Vertex Books: 1971)

[6] Olga Adamova-Sliozberg, ‘My Journey,’ reproduced in Simeon Vilensky, Till my Tale is Told: Women’s Memoirs of the Gulag, (Virago Press: 1999)

[7] Elinor Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps (London: Photolith-Merchana, 1950) 206

[8] Elinor Lipper, quoted in Robert Conquest, Kolyma: The Artic Death Camps, 177; Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History (London: Penguin Books, 2003) 284.

[9] Dmitrievna Medvedskaia, ‘Life is Everywhere,’ reproduced in Veronica Shapovalov, ed., Remembering the Darkness: Women in Soviet Prisons (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2001) 232

[10] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 235-236

[11] Evgenia Ginzburg, Into the Whirlwind, 300

[12] Anatoly Zhigulin, ‘On Work,’ reproduced in Anne Applebaum, Gulag Voices: An Anthology, (Yale University Press, 2011)

[13] Elinor Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps (London: Photolith-Merchana, 1950) 119; Janusz Bardach and Kathleen Gleeson, Man is Wolf to Man: Surviving Stalin’s Gulag (London: Simon and Schuster, 1998) 296 and 298

[14] Anne Applebaum, Gulag, 291; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 248; Emma Mason, ‘Women in the Gulag in the 1930s,’ in Illič, ed., Women in the Stalin Era, 141

[15] Veronica Shapovalov, Remembering the Darkness: Women in Soviet Prisons (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2001)

[16] Hava Volovich, ‘My Past,’ reproduced in Vilensky, Simeon, Till my Tale is Told: Women’s Memoirs of the Gulag (Indiana: Virago Press, 1999) 260

[17] Emma Mason, ‘Women in the Gulag in the 1930s,’ in Illič, ed., Women in the Stalin Era, (Palgrave: 2001)

[18] Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History, (Penguin Books: 2003)

[19] Ibid, 294

[20] Hava Volovich, ‘My Past,’ reproduced in Simeon Vilensky, Till my Tale is Told: Women’s Memoirs of the Gulag (Virago Press: 1999)

[21] Interview with Giuli Fedorovna Tsivirko, ‘Surrounded by Death,’ May 1988, reproduced in Gheith, and Jolluck, Gulag Voices, 95; Volovich, ‘My Past,’ reproduced in Vilensky, Till my Tale is Told: Women’s Memoirs of the Gulag.

[22] Anna Petrovna Zborovskaia, 291; Mason, ‘Women in the Gulag in the 1930s,’ in Illič, ed., Women in the Stalin Era, 144

[23] Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, (Harper Collins: 1973)

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS