Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe

In this, the final post in this year’s student showcase, Christian Parker considers the slow but steady growth in dissent and organised opposition in Eastern Europe in the decades following the Prague Spring. While the majority of citizens adopted an attitude of outward conformity, a small but vocal minority bravely continued to speak out against various aspects of communist rule, even in the face of sustained state repression and persecution. The state authorities adopted a range of coercive means to contain and marginalise dissent and non-conformity in both the political and the cultural sphere, however ultimately they were unsuccessful in their attempts to quell opposition to communist rule.

Silencing Dissent in Eastern Europe.

By Christian Parker

The failure of Alexander Dubcek’s attempt to develop ‘socialism with a human face’ and the forcible crushing of the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia in August 1968 was the catalyst for an ‘era of stagnation’ in Eastern Europe. In a speech made to the Polish Communist Party on 12th November 1968, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev justified the recent military intervention in Czechoslovakia and confirmed that any future attempts to deviate from the ‘common natural laws of socialist construction’ would be treated as a threat.[1] The message was clear: any significant reforms to the existing system would not be tolerated. As Tony Judt notes, this ‘Brezhnev Doctrine’ set new limits on manoeuvrability and freedom within the Eastern bloc, each state ‘had only limited sovereignty and any lapse in the Party’s monopoly of power might trigger military intervention’.[2] As long as the Soviets were prepared to maintain communism in Eastern Europe by force, any attempt at challenging the status quo appeared futile so most people adopted a policy of outward conformity and passive acceptance towards communism. However, dissent and non-conformity continued to exist in Eastern Europe, and the authorities employed extensive repression against dissidents, developing a range of coercive tactics to ensure dissent and opposition remained on the fringes of socialist society.

Charter 77 and the Birth of Organised Opposition

Perhaps the most important dissident movement to emerge in Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Prague Spring was the Charter 77 group. Charter 77 was initially formed in response to the arrest of a popular Czechoslovakian band ‘The Plastic People of the Universe’ for musical non-conformism and social subversion, after the band wrote to dissident playwright Vaclav Havel (previously famous for his 1975 Open Letter to Husak which protested the pervasive fear and ‘fraudulent social consciousness’ dominating life in Czechoslovakia after the Prague Spring), requesting his help to campaign for greater tolerance in both the political and cultural spheres.[3]

Charter 77 therefore sought to establish a ‘constructive dialogue’ with the communist party, aimed at securing a range of human rights and individual freedoms, including freedom from fear and freedom of expression which the movement demonstrated were ‘purely illusory’ in communist Czechoslovakia.[4] The movement gained further impetus from the fact that the Czechoslovakian government had recently signed the Helsinki Accords, promising to uphold ‘civil, political, economic, social, cultural…rights and freedoms’.[5]

Signatures for Charter 77 – calling on the Czechoslovakian communist party to uphold commitments to basic freedoms and human rights. Signatories were harrassed and persecuted in a variety of ways.

On its initial publication in January 1977, the Charter initially bore 243 signatures, including those of Vaclav Havel, Pavel Landovsky and Ludvik Vaculik. The state acted quickly in an attempt to prevent the campaign gaining momentum by arresting Havel, Landovsky and Vaculik whilst they were en route to the federal assembly, where they planned to deliver a copy of the Charter. The state’s retaliation to Charter 77 was wide and menacing; leading figures associated with the movement were arrested and imprisoned and signatories were targeted via a wide range of other means including arrest, intimidation, dismissal from work, denial of schooling for their children, suspension of driver’s licenses and the threat of forced exile and loss of citizenship – Geoffrey and Nigel Swain note that by the mid-1980s over 30 ‘Chartists’ had been deported, including Zdenek Mlynar, former secretary of the Czechoslovakian communist party.[6] Charter 77 backed the ‘Underground University’ (an informal institution that attempted to offer free, uncensored cultural education) but lecturers were frequently interrupted by policemen, and leading figures including philosopher Julius Tomin, were harassed and assaulted by ‘unknown thugs’. Attempts were also made to pressure workers into signing anti-Charter resolutions, though as the state representatives failed to give the workers a copy of the Charter so they could see what they were signing against, the majority refused.[7]

However, state attempts to ‘bury’ Charter 77 were largely unsuccessful. An ‘Anti-Charter Campaign’ publicised by state-run media actually helped to increase the document’s profile and despite sustained repression, by 1985 only 15 of the original signatories had removed their names. Jailing high profile Chartists proved counterproductive – John Lewis Gaddis even argues that, in the case of Vaclav Havel, it was his imprisonment 1979-1983 that gave him the ‘motive and the time to become the most influential chronicler of his generation’s disillusionment with communism’.[8] (For more on Vaclav Havel, see the previous blog post HERE). While Havel became a dominant figure, other Charter 77 dissidents also continued to undermine state authority, right up until the velvet revolution of 1989. In 1988, two leading Chartists, Rudolf Bereza and Tomas Hradilek, wrote to Soviet Premier Gorbachev demanding that anti-reformist central committee secretary Vasil Bilak be tried for high treason due to his role in the invasion of Prague in 1968. Bilak was subsequently forced into retirement from politics. Tony Judt has suggested that by ‘moralizing shamelessly in public’ Havel and the other chartists created ‘a virtual public space’ to replace the one removed by communism.[9]

Vaclav Havel, speaking at home in May 1978. A leading figure in the Czechoslovakian dissident movement, Havel was subjected to intense surveillance, restricted movments, frequent arrest, interrogation and imprisonment.

The Wider Impact of Charter 77

Charter 77 also gave impetus to dissidents elsewhere in Eastern Europe and by 1987 their manifesto supporting the establishment of human rights across Eastern Europe had gained 1,300 signatures. Immediately after the publication of Charter 77 Romanian writer Paul Goma wrote an open letter of support and solidarity which was broadcast on Radio Free Europe. Goma also wrote to Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu, asking him to sign the letter! Goma’s publication gained just over 200 signatories for the Charter, however he faced a sustained campaign of repression and intimidation as a result. The street where he lived was cordoned-off, his apartment was repeatedly broken into and his phone line was cut. Several of his fellow signatories, including worker Vasile Paraschiv, were arrested by the Securitate and beaten when visiting Goma’s apartment. After Nicolae Ceausescu made a speech on February 17 denouncing ‘traitors of the country’, Goma sent him a second letter, describing the Securitate as the real ‘traitors and enemies of Romania’. Goma was expelled from the Romanian Writers Union and arrested – his release was secured following an international outcry but after continued harassment Goma immigrated to Paris on November 20, 1977. Even this didn’t stop Romanian attempts to silence Goma, and the Securitate made two attempts to silence him permanently while he was living in Paris – sending him a parcel bomb in February 1981 and attempting to assassinate him with a poisoned dart on January 13, 1982.[10]

Paul Goma’s case was not an isolated incident – while attempted assassinations abroad were rare, this tactic was occasionally used to silence particularly troublesome East European dissidents. For example, writer and broadcaster Georgi Markov’s defection to London from Bulgaria led to him being declared a persona non grata, and he was issued a six year prison sentence in absentia. He continued speaking about against the communist regime in Bulgaria on the BBC World Service and Radio Free Europe, and on 7th September 1978 a Bulgarian Security Agent fired a poisoned ricin pellet into Markov’s leg while he was waiting at a bus stop in central London. He died a few days later (For more on the Georgi Markov assassination see the previous blog post HERE).

Dissent and Non-Conformity in the GDR

In many respects, dissent in the GDR was the result of unique conditions within the communist bloc: it was arguably the only state which, even in the wake of the failed Prague Spring, could still boast an ‘informal and even intra-Party Marxist opposition’, a class of intellectuals who attacked the regime from the political ‘left’.[11] Thus, Wolfgang Harich desired a reunified Germany and wrote about a ‘third-way’ between Stalinism and Capitalism, another variant of ‘socialism with a human face’. Harich was particularly critical of the regime’s ‘bureaucratic deviation’ and ‘illusions of consumerism’ and similarly Robert Havemann and Wolf Biermann attacked the regime for supporting mass consumption and privately owned consumer goods. Rudolf Bahro, another leading East German dissident, is best known for his essay The Alternative, which Judt describes as ‘an explicitly Marxist critique of real existing socialism’.[12]

State leaders would not tolerate these revisionists, despite their Marxist leanings and the feared East German Stasi employed a range of methods to silence them. Mary Fulbrook notes that isolating dissident intellectuals was done ‘with relative ease by the regime’.[13] Thus Harich was imprisoned, Havemann was placed under house arrest and Bierman and Bahro were both forced into exile in the West. The case of Bahro provides a particularly disturbing insight into the lengths the Stasi were prepared go to. Bahro, dissident writer Jürgen Fuchs and outlawed Klaus Renft Combo band member Gerulf Pannach had all been held in Stasi prisons at a similar time and all later died from an unusual form of cancer. After the collapse of communism an investigation discovered that that Stasi had been using radiation to ‘tag’ dissidents. One of Bahro’s manuscripts was also discovered to have been irradiated so it could be tracked across to the west.[14]

The pervasive influence of the Stasi meant that any criticism of the East German regime, however mild, could have severe repercussions. Erwin Malinowski, who wrote a letter of protest about the treatment of his son, who was imprisoned after applying to move to West Germany in January 1983, was placed in a Stasi remand prison for seven months and then served two years further imprisonment for ‘anti-state agitation’. His son was eventually ‘bought free’ by the West Germans, one of the measures through which dissenters could escape the GDR. West German money also secured the release of Josef Kniefel who in March 1980 attempted to blow up the Soviet tank monument in Karl-Marx-Stadt in protest over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan the previous December. He had previously served a ten month prison sentence for attacking Stalin’s crimes against humanity and the role of the ruling parties of Eastern Europe.[15] For other dissidents, ‘repressive tolerance’ and limited publishing space proved effective measures by which the GDR could assert control. The GDR’s response to dissent was effective, however despite the relative success of the Stasi in isolating prominent dissident intellectuals, the regime never achieved total success in quelling dissent, discontent, or opposition.[16]

During the 1970s and 1989s, the peace movement, environmental movement and Protestant Church also provided citizens with outlets to vent their frustrations. Many who joined these organisations sought to improve the regime from within, disillusioned with the lack of respect for the environment and public health encouraged by growing industrialisation and the use of nuclear energy, something which was exacerbated by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986. To control environmental dissidents, the state banned the publication of data relating to the environmental situation in the GDR. Moreover, Stasi attempts to infiltrate and break up these groups met some success. For example, the main Church environmental movement Kirchliche Forschungsheim Wittenburg was infiltrated by the Stasi to the point where it lost its relevance in the wider environmental movement. However, the organisational networks, political strategies and the experience built up during the 1980s, set the stage for these groups to later serve as a vital part of the revolution of 1989. Such vociferous opposition thus taught East German dissidents the ‘complex arts of self-organization and political pressure group work under dictatorial conditions’[17]

The GDR not only took a hard line against intellectual dissent but also persecuted cultural non-conformity. For example, the Klaus Renft Combo, described by Funder as ‘the wildest and most popular rock band in the GDR’, agitated the state so much that at the bands attendance at the yearly performance licensing committee meeting in 1975 they were informed that ‘as a combo … [they] no longer existed’. Copies of their records disappeared from the shelves, and the radio stations were prohibited from playing their songs. Klaus Renft was exiled west, and several other band members were imprisoned. Despite this, the GDR failed to stop the band altogether, and they gained something of a cult following because of their repression by the state.[18] Attempts by the GDR and other East European regimes to prevent their citizens’ exposure to ‘Western culture’ were ultimately unsuccessful however, with bootleg records and cassette tapes smuggled in and distributed on the black market and the increased availability of television sets and video recorders in the 1980s allowing citizens access to Hollywood films and TV series such as ‘Dallas’. (For more information about the impact of popular culture on communist Eastern Europe see the previous blog posts ‘Video May Have Killed the Radio Star, But Did Popular Culture Kill Communism?’ HERE and ‘Rocking the Wall’ HERE).

The Klaus Renft Combo – In 1975 the band were targeted due to their ‘subversive lyrics’ and were forcibly disbanded. Members were arrested and forced to leave the GDR for West Germany.

Conclusion

It is clear that the regimes of Eastern Europe possessed a vast array of techniques with which they attempted to silence those who attempted to oppose or criticise communism. These dissidents could not directly bring down the regimes they spoke out against; partly due to the success of state attempts to contain, control them and limit their influence, and partly because they lacked sufficient popular mandate amongst their populations. Certainly though, through their bravery and continued campaigns in the face of persecution and oppression they created hope, and in many ways they helped to set the precedent for the revolutionaries of 1989.

About the Author

Christian Parker has just completed his BA (Hons) in History at Swansea University. In his final year of study, Christian specialised in East European History. After taking the next year off to travel, Christian hopes to begin postgraduate study in 2013.

[1] The Brezhnev Doctrine (12 November 1968) available online @ http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1968brezhnev.asp

[2] Tony Judt, PostWar (Plimlico, 2007), 446

[3] Dear Dr. Husak (April 1975) – available online @ http://vaclavhavel.cz/showtrans.php?cat=eseje&val=1_aj_eseje.html&typ=HTML

[4] Declaration of Charter 77, published in January 1977, available online @ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/czechoslovakia/cs_appnd.html

[5] Helsinki Accords (1 August 1975) – excerpt available online @ http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/245

[6] Geoffrey Swain and Nigel Swain, Eastern Europe Since 1945 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 185

[7] Sabrina Ramet, Social Currents in Eastern Europe, (Duke University Press, 1995), 126

[8] John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, (Penguin 2007), 191

[9] Tony Judt, PostWar (Plimlico, 2007), 577

[10] Dennis Deletant, Ceausescu and the Securitate, Coercion and Dissent in Romania, 1965-1989, (Hurst & Co., 1995), 235-242

[11] Tony Judt, Post War, (Plimlico, 2007), 573; Christian Joppke, ‘Intellectuals, Nationalism and the Exit From Communism: The Case of East Germany’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 37, 2 (April 1975), 216.

[12] David Childs and Richard Popplewell, The Stasi, The East German Intelligence and Security Service, (Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996), 99; Tony Judt, Post War, (Plimlico, 2007), 573-574.

[13] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995), 176.

[14] Anna Funder, Stasiland, (Granta Books, 2004), 191

[15] David Childs and Richard Popplewell, The Stasi, The East German Intelligence and Security Service, (London: Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996), 97-98

[16] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995) 201.

[17] Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship, Inside the GDR, 1949-1989, (Oxford University Press, 1995)

[18] Anna Funder, Stasiland, (Granta Books, 2004), 185-191

2011: A Quick Review

2011 is a year that has prompted numerous historical comparisons, even before it has ended. This has been a year marked by economic turmoil, widespread international protest and revolutionary activity, as evidenced by Time Magazine’s recent announcement that their coveted ‘person of the year’ was to be awarded to ‘The Protestor‘. Throughout 2011, global news coverage has frequently been dominated by the growing wave of protest and demonstrations that swept the Arab World; quickly dubbed the ‘Arab Spring’ by international media and drawing frequent comparisons with the East European revolutions of 1989. Some (including, recently, Eric Hobsbawm) have suggested that comparisan with the ‘Spring of Nations’ of 1848 is more fitting although many have questioned the value of either historical analogy. Similarly, almost twenty years to the day, in the last weeks of 2011, mounting protests against electoral fraud in Russia have evoked memories of the collapse of the communist monopoly of power and the break-up of the USSR in 1991, with the last Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev recently advising current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to ‘learn the lesson of 1991’ and resign from power, although Russia-watcher Mark Galeotti has suggested that 1905 may turn out to be a more fitting historical parallel.

The increasingly uncertain economic climate and global financial downturn also dominated news coverage throughout 2011, particularly of late due to the growing crisis in the Eurozone. Across central and eastern Europe, economic crisis and social insecurity has generated fresh concern about ‘ostalgie’ with the release of surveys suggesting high levels of nostalgia for the communist era. In recent polls conducted in Romania 63% of participants said that their life was better under communism, while 68% said they now believed that communism was ‘a good idea that had been poorly applied’. Similarly, a survey conducted in the Czech Republic last month revealed that 28% of participants believed they had been ‘better off’ under communism, leading to fears of a growth in ‘retroactive optimism‘.

Much of the subject matter presented here at The View East aims to combine historical analysis with more contemporary developments. During 2011 a range of blog posts have covered topics as diverse as the Cold War space race (with posts about Sputnik and the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin‘s first successful manned space flight); the role of popular culture (and specifically, popular music in the GDR) in undermining communism; the use and abuse of alcohol in communist Eastern Europe; espionage and coercion (with posts relating to the East German Stasi, Romanian Securitate and the notorious murder of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov) and in relation to continuing efforts to commemorate contested aspects of modern history including Katyn; the construction of the Berlin Wall, German reunification, Stalin’s legacy and the continuing controversy over Soviet-era war memorials. This summer also saw the first ‘student showcase’ here at The View East, which was a great success, with a series of excellent guest authored posts on a range of fascinating topics, researched and written by some of my students at Swansea University.

Something that I constantly stress to my students is the need to recognise how our knowledge and understanding of modern central and eastern Europe was, in many respects, transformed as new evidence and sources of information became accessible to historians of Eastern Europe after the collapse of communism 1989-1991; and the ways in which our understanding continues to evolve as new information and perspectives continue to emerge today. So, with that in mind, here is a quick review of some of my own personal favourite topics of interest, events and developments during 2011. This short summary is by no means exhaustive so please feel free to add suggestions of your own in the comments section below!

Anniversaries for Reagan and Gorbachev

February 2011 marked the centenary of Ronald Reagan’s birth. Today, former US President and ‘Cold Warrior’ Reagan remains highly regarded throughout the former communist block, where he is widely credited with helping to end the Cold War and open a pathway for freedom across Eastern Europe. A series of events were thus organised to mark the occasion across central and eastern Europe, where several streets, public squares and landmarks were renamed in Reagan’s honour and and the summer of 2011 saw statues of Reagan popping up in several former communist block countries, including Poland, Hungary and Georgia. To mark the centenary, the CIA also released a collection of previously classified documents, along with a report on ‘Ronald Reagan, Intelligence and the End of the Cold War’ and a series of short documentary style videos that were made to ‘educate’ Reagan about the USSR on a range of topics including the space programme, the Soviet war in Afghanistan and the Chernobyl disaster, which can be viewed here. An exhibition held at the US National Archives in Washington DC also displayed examples of Reagan’s personal correspondence including a series of letters exchanged with Mikhail Gorbachev and the handwritten edits made to Reagan’s famous ‘Evil Empire’ speech of 1983.

A statue of former US President Ronald Reagan, unveiled in the Georgian capital Tblisi in November 2011. The centenary of Reagan's birth was celebrated throughout the former communist block in 2011.

Today, citizens of the former East Block tend to view Reagan much more kindly than his Cold War counterpart, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev who celebrated his 80th birthday back in March. Still feted in the West, Gorbachev was the guest of honour at a celebratory birthday gala in London and and was also personally congratulated by current Russian President Medvedev, receiving a Russian medal of honour. In a series of interviews, Gorbachev claimed he remained proud of role in ending communism, although for many, his legacy remains muddied. April 2011 saw the 25th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, while August 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the failed military coup launched by communist hardliners hoping to depose Gorbachev from power and halt his reforms and finally, the 25 December 2011 was 20 years to the day since Gorbachev announced his resignation from power and the formal dissolution of the USSR. Recently released archival documents have also provided historians with more detailed information about the dying days of the Soviet Union as a desperate Gorbachev tried to hold the USSR together.

March 2011 - Russian President Dmitry Medvedev shakes hands with Mikhail Gorbachev during a meeting to celebrate his 80th birthday. Gorbachev was awarded the Order of St Andrew the Apostle, Russia's highest honour.

Half a Century Since the Construction of the Berlin Wall

August 2011 marked 50 years since the construction of the famous wall which divided Berlin 1961-1989 and became one of the most iconic symbols of Cold War Europe. The anniversary was commemorated in Germany as I discussed in my earlier blog post here and was also widely covered by international media including the Guardian and the BBC here in the UK. I particularly enjoyed these interactive photographs, published in Spiegel Online, depicting changes to the East-West German border. In October, the CIA and US National Archives also released a collection of recently declassified documents relating to the Berlin Crisis of August 1961, which have been published online here.

13 August 2011 - A display in Berlin commemorates the 50th anniversary of the construction of the Berlin Wall.

Thirty Years Since Martial Law Crushed Solidarity in Poland

13 December marked 30 years since General Jaruzelski’s declaration of Martial Law in Poland in 1981, as the emergent Solidarity trade union was declared illegal and forced underground. NATO have released a fascinating series of archived documents relating to events in Poland 1980-81 which have been published online here. Today Jaruzelski still argues that he ordered the domestic crackdown to avoid Soviet invasion, claiming in a recent book that his actions were a ‘necessary evil’ . but intelligence contained in the newly available NATO reports suggest that the Soviet leadership were actually ‘keen to avoid’ military intervention in Poland. Fresh attempts to prosecute 88 year old Jaruzelski for his repressive actions were halted due to ill health in 2011, as the former communist leader was diagnosed with lymphoma in March 2011 and has been undergoing regular chemotherapy this year.

13 December 2011 marked 30 years since General Wojciech Jaruzelski's declaration of Martial Law in Poland, designed to crush the growing Polish opposition movement, Solidarity.

The Communist-Era Secret Police

Stories about communist-era state security are always a crowd pleaser and 2011 saw a series of new revelations from the archives of the notorious East German Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or Stasi. I particularly liked the archived photos that were published in Spiegel Online, taken during a course to teach Stasi agents the art of disguise, as discussed in my previous blog post here and, in a similar vein, information from Polish files about espionage techniques used by Polish State Security which was published in October. In November, new research published in the German Press suggested that the Stasi had a much larger network of spies in West Germany than was previously thought, with over 3000 individuals employed as Inofizelle Mitarbeiter or ‘unofficial informers’, to spy on family, friends, neighbours and colleagues. The Stasi even compiled files on leading figures such as German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) and former East German leader Erich Honecker, gathering information that was later used as leverage to force his resignation in October 1989. A new book published in September also detailed the extent of Stasi infiltration in Sweden, with information published in the German media suggesting that Swedish furniture manufacturer IKEA used East German prisoners as a cheap source of labour in the 1970s and early 1980s.

‘Tourist with Camera’ – a favoured disguise used by Stasi surveillance agents, unearthed from the Stasi archives and part of a new exhibition that went on display in Germany earlier this year.

The Death of Vaclav Havel

2011 ended on something of a sombre note, as news broke of the death of communist-era dissident and former Czechoslovakian/Czech President Vaclav Havel on 18 December. An iconic figure, Havel’s death dominated the news in the lead up to Christmas, (only eclipsed by the subsequent breaking news about North Korean leader Kim Jong Il’s death on December 17!) with numerous obituaries and tributes to Havel and his legacy appearing in the media (such as this excellent tribute in The Economist, ‘Living in Truth‘), as discussed in more detail in my recent blog post here. Havel’s funeral on 23 December was attended by world leaders, past and present and received widespread media coverage. In recent interviews, such as this one, given shortly before his death, Havel commented on a range of contemporary issues including the Arab revolutions and the global economic crisis. RIP Vaclav – you will be missed.

December 2011 - News breaks of the death of playwright, communist-era dissident and former Czech President Vaclav Havel. Hundreds of candles were lit in Prague's Wenceslas Square in his memory, thousands of mourners gathered to pay their respects and tributes poured in from around the globe.

The Growth of Social Networking

The use of social networking as a tool for organising and fuelling protest and opposition movements has also been a regular feature in the news throughout 2011 with particular reference to the Arab Spring, the UK riots and the recent ‘Occupy’ movement. Many more universities and academics are also now realising the potential benefits of using social media sites to promote their interests, and achievements, disseminate their research to a wider audience and engage in intellectual debate with a wider circle of individuals working on similar areas of interest, both within and beyond academia. The potential benefits of Twitter and other social networking sites for academics has been promoted by the LSE and their Impact Blog during 2011, including this handy ‘Twitter guide for Academics‘. On a more personal note, promoting The View East via Twitter has also helped me develop a much stronger online profile and contributed to an increased readership in 2011, something I discussed further in a September blog post here.

As 2011 ends, our twitter feed @thevieweast is heading for 500 regular twitter followers; most days The View East receives well over 100 hits, the number of regular email subscribers has almost doubled and I’ve been able to reach a much wider audience – some older blog content I wrote relating to Solidarity was recently published in a Macmillan textbook History for Southern Africa and in the last twelve months I have given interviews to ABC Australia, Voice of America, and Radio 4, all in relation to subjects I’d written about here at The View East. So, as 2011 draws to a close, I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all of you who have read, commented, followed and re-tweeted from The View East in 2011 – A very Happy New Year to you all, and I’m looking forward to more of the same in 2012!

The Curious Case of the Poisoned Umbrella: The Murder of Georgi Markov

This week marks 33 years since the murder of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov, who was poisoned in London on 7 September 1978. Markov’s assassination, an operation conducted by the Bulgarian Secret Services (the Darzhavna Sigurnost or DS) under the guidance of the Soviet KGB, contained all the essential ingredients of a Cold War spy thriller: mystery, intrigue, nameless, faceless assassins and a nifty James Bond style gadget used as a murder weapon. Markov’s murder also led to widespread outrage and concern – after all, he was killed in the centre of London, in broad daylight, during rush hour, by communist secret agents who appeared to be able to kill with impunity, before vanishing into thin air …

Georgi Markov

Georgi Markov, author, broadcaster and communist-era dissident, who was murdered in extraordinary circumstances in London on 7 September 1978.

Born in Sofia in 1929, Georgi Markov studied industrial chemistry at university in the 1940s, before working as a chemical engineer and technical school teacher. However, Markov’s true love was literature and he went on to become an acclaimed novelist, playwright and TV script writer. Many of his works were critical of communist Bulgaria – Markov had described his novel ‘The Great Roof’ as ‘a symbol of the roof of lies … that the communist regime has constructed over Bulgaria’ – and as a result, were often prohibited from publication. In 1969 Markov left Bulgaria for the West, travelling first to Italy before settling in Londonin the 1970s, where he learned English and worked as a broadcaster and journalist for the Bulgarian section of the BBC World Service, Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Europe. Several of Markov’s novels were published and his plays were performed to critical acclaim in the UK during the 1970s.

Markov’s defection to the West meant that he quickly became persona non grata back in Bulgaria. In 1972 his membership in the Union of Bulgarian Writers was suspended and he was sentenced (in absentia) to a six year prison sentence for his defection. Markov’s previously published works were withdrawn from libraries and bookshops and his name was not permitted to be mentioned in the official Bulgarian media until 1989. Even from afar however, Markov proved a continuing thorn in the side of the Bulgarian Communist Party, criticising the regime in radio broadcasts for the BBC Bulgarian service. Between 1975 and 1978 Markov worked on a series of ‘In Absentia’ reports – analysis of life in Communist Bulgaria, broadcast weekly on Radio Free Europe. His continued criticism of the Communist government and personal attacks against party leader, Todor Zhivkov, made Markov an enemy of the regime. A recently declassified letter, sent from the DS to the KGB in 1975 complained that Markov’s radio broadcasts ‘insolently mocked’ the communist party, and ‘encouraged dissidence’ in Bulgaria. The DS kept a surveillance file on Markov using the code name ‘Wanderer’ and whilst in London he received several death threats via telephone. Markov’s publisher, David Farrer, later said that ‘he (Markov) knew his activities made him a possible target for assassination’.

The Case of the Poisoned Umbrella.

On the morning of 7 September 1978, Georgi Markov was on his way to work at the BBC. While waiting at a bus stop near Waterloo bridge alongside several other commuters, he felt a sudden, sharp pain on the back of his right thigh, which he later described as ‘similar to an insect bite’. A nearby man (described as ‘heavy set with a foreign accent’) then briefly stooped to pick up an umbrella from the ground and mumbled ‘I’m sorry’, before hurriedly crossing the street and jumping into a taxi. Upon closer examination after he arrived at work, Markov discovered a small, painful red bump on the back of his leg. Over the course of the working day he became progressively sicker and was admitted to hospital that evening, suffering from a high fever. He died a few days later, on 11 September.

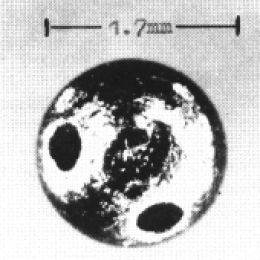

Georgi Markov had been poisoned by a small pellet fired into his leg on that fateful morning. During the subsequent autopsy, forensic pathologists discovered a spherical metal pellet the size of a pin-head embedded in his leg, containing holes drilled at right angles to each other, to form an “X” shaped well inside the pellet. The pellet had been filled with 0.2mg of the deadly poison Ricin and then covered with a waxy coating that was designed to melt at 37 degrees celsius (the temperature of the human body), thus triggering the release of the poison into the bloodstream.

Suspicion that a specially designed ‘umbrella-gun’ had been used as the murder weapon led to Markov’s assassination being dubbed ‘The case of the poisoned umbrella’. Diagrams were even produced to demonstrate how the umbrella may have been adapted into a lethal killing machine with a ‘poisoned tip’, and former KGB officers have since claimed that such a device had indeed been designed. However, subsequent theories have suggested that the poisonous pellet may have been directly injected by hypodermic needle or fired into Markov’s leg by a specially adapted pen, with the umbrella being dropped nearby as a distraction. Following the autopsy, the coroners’ ruling determined that Markov had been ‘unlawfully killed’.

Diagram depicting the 'umbrella-gun' that many people believe was used to fire the poisoned pellet into Georgi Markov's leg while he stood waiting for a London bus.

The Murder.

Evidence suggests that Markov’s assassination was ordered from the highest levels, with the full knowledge and involvement of both the Bulgarian DS and the Soviet KGB. Prior to the events of 7 September 1978, the DS had sought advice from the KGB about how best to ‘neutralise’ Markov, and two previous attempts had been made on his life: a toxin slipped into his drink at a dinner party and a previous attempt on his life during a visit to Sardinia, both of which had failed. It has been suggested that the date chosen for the third assassination attempt – 7 September – was because this was Zhivkov’s birthday, and Markov’s murder was to act as some sort of ‘gift’ to the Bulgarian leader.

Recently declassified Bulgarian Secret Service files have confirmed the close nature of the relationship between the DS and KGB, although KGB representatives were keen to ensure there was no ‘trail’ directly linking Markov’s death toMoscow. However, the files show that two high-level Bulgarian secret-service delegations visited Moscow in the months leading up to the murder, where the dynamics of the Markov case were specifically discussed with technical experts from KGB laboratories. According to the files, an Italian-born, Dane Francesco Gullino, codenamed ‘Piccadilly’, was recruited by the DS to act as the assassin, with records also documenting training and a series of payments made to ‘Picadilly’.

Even today, mystery and controversy still surround Markov’s death. In 2010 TIME Magazine listed Markov’s murder as one of their ‘Top 10 Assassination Plots’ and in 1998, Bulgarian President Peter Stoyanov, described the assassination as ‘one of the darkest moments’ in communist Bulgaria. No charges have ever been bought though, despite renewed interest in the case in the post-Cold War period. In September 2008 a team of counter-terrorism experts from Scotland Yard travelled to Bulgaria to access archived documents on the Markov case. Much of the evidence has been destroyed however, leading to accusations of a Bulgarian cover up – in 1992 General Vladimir Todorov, former Bulgarian intelligence chief, was sentenced to 16 months in jail for destroying 10 volumes of material relating to Markov’s death while two other individuals suspected of involvement in the assassination both died in mysterious circumstances in the 1990s – and Bulgarian prosecutors have now officially closed the investigation, under legislation which allows unsolved criminal cases to be dropped after 30 years.

Interestingly, ten days before Markov’s murder, a similar assassination attempt was made on another Bulgarian exile, Vladimir Kostov, while he was waiting at a Paris metro station. Like Markov, Kostov came down with a high fever and was hospitalized, where Doctors found the same kind of metal pellet embedded in his skin. On this occasion however, Kostov survived: possibly because he had not been shot at point blank range; possibly because the coating on the pellet had failed to fully dissolve, meaning that only a small quantity of Ricin was able to enter his blood or possibly because he was wearing a thick sweater on the day of the attack, which may have provided enough resistance to prevent the pellet completely penetrating his skin. However, Kostov’s case suggests that the attack on Markov may not have been an isolated case, but was perhaps intended as part of a wider strategy aimed at ‘silencing’ troublesome dissidents overseas. In the post-Cold War era, numerous cases including the dioxin poisoning of Ukrainian opposition leader (and later President) Viktor Yushchenko in the run-up to the 2004 elections; the still unsolved October 2006 murder of Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya and the November 2006 death of former KGB and FSB officer Alexander Litvinenko from radiation poisoning after exposure to polonium in London have drawn fresh comparisons with the Markov case, suggesting that when it comes to politically-motivated assassination, old communist-era habits may be hard to break.

(For a more detailed overview of recent cases suspected of involving politically motivated poisoning, see THIS Open Democracy article by Zygmunt Dzieciolowski).

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS