A Visit to Vilnius

Earlier this month I visited Vilnius, to participate in a conference, ‘The Soviet Past in the Post-Soviet Present’, organised by Melanie Ilic (University of Gloucestershire) and Dalia Leinarte (Vilnius University). The conference centred around exploring the implications of using oral testimony, memory studies and life writing when researching aspects of everyday life in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The two day conference comprised a fantastic mixture of interesting and thought-provoking presentations on a diverse range of research projects relating to broader themes including identity construction, gender, nostalgia and trauma studies. I delivered a paper entitled ‘Conversations about Crime in Communist East Central Europe’, focusing on my own use of oral testimony during my research into crime in late-socialist era East Central Europe, and the resulting question and answer session was pretty lively, giving me lots of food for thought about popular perceptions of morality and criminality under communism! In addition to a series of 20 minute papers delivered in the ‘traditional’ conference style, we were also treated to a reading from the transcript of an interview-style conversation between Barbara Alpern Engel and Anastasia Posadskaya, two scholars who conducted several interviews for their seminal study A Revolution of Their Own: Voices of Women in Soviet History (Boulder, Colorado, 1998). This was followed by a question and answer session with Barbara Engel herself, who joined us live via Skype.

I stayed on for an extra day to explore Vilnius after the conference ended – as I only had 24 hours there I confined myself to exploring the Old Town and surrounding areas, but still found plenty to see and do and I’d certainly recommend visiting if you have the chance! Vilnius itself was lovely, thoroughly charming and quietly cultivating a relaxed ‘shabby chic’ feel as the post-communist renovation of the city’s stunning architecture gradually continues (Vilnius Old Town gained UNESCO World Heritage status in 2004), combined with more modern developments. The contrast between ‘old’ and ‘new’ Vilnius was particularly apparent when looking out across the city from the top of Gediminas Castle:

This contrast was also visible when wandering around the city, as the more ‘modern’ feel of the broad streets and designer fronted stores along Gedimo prospect juxtaposed with the more traditional narrow, winding, cobbled roads leading past the smaller souvenir shops, cafes and restaurants snaking down Pilles Street and throughout the University quarter.

Of course, I visited several of the main tourist attractions including the Cathedral, the remains of Gediminas Castle, St Annes Church (along with several other beautiful churches) and the Dawn Gate. I also enjoyed sampling some traditional Lithuanian cuisine!

Vilnius also had a very ‘arty’ feel to it, something that was particularly apparent as I wandered through Uzupis, a bohemian city district that declared itself an independent republic in 1997! However, I also enjoyed stumbling upon the street art dotted around the old town, and was intrigued to spot several trees that appeared to be ‘dressed’ in brightly knitted jumpers. I know we’re heading into autumn and that the Baltic winter is notoriously cold, but do the trees really need cosy knitwear?! A quick enquiry on Twitter when I returned informed me that the tree jumpers were an example of ‘yarn bombing’ or ‘guerilla knitting’ a form of urban art that I hadn’t seen before!

The quiet, relaxed feel to Vilnius belies its turbulent recent history, however. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the visit for me was exploring some of the lingering traces of Soviet occupation. This was most evident in the Soviet-era kitsch on sale in the many flea markets and souvenir stalls set out (similar to that I’ve seen elsewhere in the former Soviet bloc) and the tall Soviet statues which remain proudly standing at the four corners of Žaliasis tiltas (Green Bridge), over the river Neris.

“Welcome to Vilnius, Comrade!” – Soviet-era statues still stand at the four corners of Žaliasis tiltas (Green bridge)

However, there is an argument to be made that the brutal nature of Soviet occupation means that the psychological legacy rather than the physical traces of communism lingers longest for many Lithuanians. With that in mind, one particularly striking aspect of my time in Vilnius was my visit to the Museum of Genocide Victims, an extensive exhibition housed in the former KGB headquarters on Gedimo prospect, which charts the oppression and suffering of the Lithuanian people under successive foreign occupations between 1939-1991. The exhibition takes you through periods of successive Soviet (1940-1941), German (1941-1944) and Soviet again (1944-1991) occupations, although the Nazi occupation receives a lot less attention that the years of Soviet domination – this is a sobering tale of suffering and oppression, charting partisan warfare, collaboration, opposition, dissent, imprisonment and mass deportation.

Letters written by Lithuanian citizens who were interred in prison camps during the Stalinist era. The letter on the left has been censored by the camp authorities.

The final part of the exhibition guides visitors down into the basement, formerly used as a prison by the KGB, where visitors can tour the cells, prison exercise yards and even visit the former ‘execution room’. By now, I think of myself as something of a veteran visitor to such sites – I regularly read and teach about the ‘darker aspects’ of totalitarian regimes, and have visited Auschwitz, the Stasi Headquarters in Berlin and Budapest’s ‘Museum of Terror’ in recent years. However, the tour of the former prison still affected me on a personal level (more so, I found, than similar visits in Berlin and Budapest, but less than my visit to Auschwitz , which was emotionally draining, an experience I previously blogged about HERE). There was something about the heavy feeling that settled in my stomach while my footsteps echoed down the dark, dank, narrow corridors (the fact that I was entirely alone in an otherwise deserted basement prison probably contributed to this!). I felt increasingly unnerved and unsettled as I peered through the cell doors to view the ‘punishment cells’ set up to demonstrate how prisoners would be forced to stand on narrow platforms surrounded by icy water for hours on end (inevitably to plunge into the freezing water when they lost their balance or lost consciousness); illustrating how prisoners condemned to isolation were incarcerated alone in cramped, dark boxes for days (and sometimes weeks) on end and how padded walls were installed in some cells to block out the sound of cries of pain from prisoners subjected to physical torture. All of this was accompanied with information about various individuals who had spent time (and sometimes even died) whilst in the prison. I’d certainly recommend visiting the museum if you are in Vilnius, but I must confess that I was glad to escape out into the fresh air and the sunshine when my tour ended.

Sacks of torn KGB files – when Lithuania declared independence from Soviet rule and communism crumbled, the KGB attempted to hide their worst ‘crimes’ by destroying incriminating evidence.

The Curious Case of the Poisoned Umbrella: The Murder of Georgi Markov

This week marks 33 years since the murder of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov, who was poisoned in London on 7 September 1978. Markov’s assassination, an operation conducted by the Bulgarian Secret Services (the Darzhavna Sigurnost or DS) under the guidance of the Soviet KGB, contained all the essential ingredients of a Cold War spy thriller: mystery, intrigue, nameless, faceless assassins and a nifty James Bond style gadget used as a murder weapon. Markov’s murder also led to widespread outrage and concern – after all, he was killed in the centre of London, in broad daylight, during rush hour, by communist secret agents who appeared to be able to kill with impunity, before vanishing into thin air …

Georgi Markov

Georgi Markov, author, broadcaster and communist-era dissident, who was murdered in extraordinary circumstances in London on 7 September 1978.

Born in Sofia in 1929, Georgi Markov studied industrial chemistry at university in the 1940s, before working as a chemical engineer and technical school teacher. However, Markov’s true love was literature and he went on to become an acclaimed novelist, playwright and TV script writer. Many of his works were critical of communist Bulgaria – Markov had described his novel ‘The Great Roof’ as ‘a symbol of the roof of lies … that the communist regime has constructed over Bulgaria’ – and as a result, were often prohibited from publication. In 1969 Markov left Bulgaria for the West, travelling first to Italy before settling in Londonin the 1970s, where he learned English and worked as a broadcaster and journalist for the Bulgarian section of the BBC World Service, Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Europe. Several of Markov’s novels were published and his plays were performed to critical acclaim in the UK during the 1970s.

Markov’s defection to the West meant that he quickly became persona non grata back in Bulgaria. In 1972 his membership in the Union of Bulgarian Writers was suspended and he was sentenced (in absentia) to a six year prison sentence for his defection. Markov’s previously published works were withdrawn from libraries and bookshops and his name was not permitted to be mentioned in the official Bulgarian media until 1989. Even from afar however, Markov proved a continuing thorn in the side of the Bulgarian Communist Party, criticising the regime in radio broadcasts for the BBC Bulgarian service. Between 1975 and 1978 Markov worked on a series of ‘In Absentia’ reports – analysis of life in Communist Bulgaria, broadcast weekly on Radio Free Europe. His continued criticism of the Communist government and personal attacks against party leader, Todor Zhivkov, made Markov an enemy of the regime. A recently declassified letter, sent from the DS to the KGB in 1975 complained that Markov’s radio broadcasts ‘insolently mocked’ the communist party, and ‘encouraged dissidence’ in Bulgaria. The DS kept a surveillance file on Markov using the code name ‘Wanderer’ and whilst in London he received several death threats via telephone. Markov’s publisher, David Farrer, later said that ‘he (Markov) knew his activities made him a possible target for assassination’.

The Case of the Poisoned Umbrella.

On the morning of 7 September 1978, Georgi Markov was on his way to work at the BBC. While waiting at a bus stop near Waterloo bridge alongside several other commuters, he felt a sudden, sharp pain on the back of his right thigh, which he later described as ‘similar to an insect bite’. A nearby man (described as ‘heavy set with a foreign accent’) then briefly stooped to pick up an umbrella from the ground and mumbled ‘I’m sorry’, before hurriedly crossing the street and jumping into a taxi. Upon closer examination after he arrived at work, Markov discovered a small, painful red bump on the back of his leg. Over the course of the working day he became progressively sicker and was admitted to hospital that evening, suffering from a high fever. He died a few days later, on 11 September.

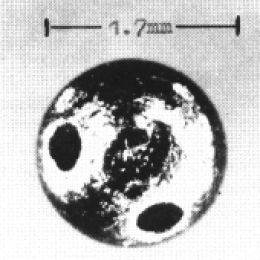

Georgi Markov had been poisoned by a small pellet fired into his leg on that fateful morning. During the subsequent autopsy, forensic pathologists discovered a spherical metal pellet the size of a pin-head embedded in his leg, containing holes drilled at right angles to each other, to form an “X” shaped well inside the pellet. The pellet had been filled with 0.2mg of the deadly poison Ricin and then covered with a waxy coating that was designed to melt at 37 degrees celsius (the temperature of the human body), thus triggering the release of the poison into the bloodstream.

Suspicion that a specially designed ‘umbrella-gun’ had been used as the murder weapon led to Markov’s assassination being dubbed ‘The case of the poisoned umbrella’. Diagrams were even produced to demonstrate how the umbrella may have been adapted into a lethal killing machine with a ‘poisoned tip’, and former KGB officers have since claimed that such a device had indeed been designed. However, subsequent theories have suggested that the poisonous pellet may have been directly injected by hypodermic needle or fired into Markov’s leg by a specially adapted pen, with the umbrella being dropped nearby as a distraction. Following the autopsy, the coroners’ ruling determined that Markov had been ‘unlawfully killed’.

Diagram depicting the 'umbrella-gun' that many people believe was used to fire the poisoned pellet into Georgi Markov's leg while he stood waiting for a London bus.

The Murder.

Evidence suggests that Markov’s assassination was ordered from the highest levels, with the full knowledge and involvement of both the Bulgarian DS and the Soviet KGB. Prior to the events of 7 September 1978, the DS had sought advice from the KGB about how best to ‘neutralise’ Markov, and two previous attempts had been made on his life: a toxin slipped into his drink at a dinner party and a previous attempt on his life during a visit to Sardinia, both of which had failed. It has been suggested that the date chosen for the third assassination attempt – 7 September – was because this was Zhivkov’s birthday, and Markov’s murder was to act as some sort of ‘gift’ to the Bulgarian leader.

Recently declassified Bulgarian Secret Service files have confirmed the close nature of the relationship between the DS and KGB, although KGB representatives were keen to ensure there was no ‘trail’ directly linking Markov’s death toMoscow. However, the files show that two high-level Bulgarian secret-service delegations visited Moscow in the months leading up to the murder, where the dynamics of the Markov case were specifically discussed with technical experts from KGB laboratories. According to the files, an Italian-born, Dane Francesco Gullino, codenamed ‘Piccadilly’, was recruited by the DS to act as the assassin, with records also documenting training and a series of payments made to ‘Picadilly’.

Even today, mystery and controversy still surround Markov’s death. In 2010 TIME Magazine listed Markov’s murder as one of their ‘Top 10 Assassination Plots’ and in 1998, Bulgarian President Peter Stoyanov, described the assassination as ‘one of the darkest moments’ in communist Bulgaria. No charges have ever been bought though, despite renewed interest in the case in the post-Cold War period. In September 2008 a team of counter-terrorism experts from Scotland Yard travelled to Bulgaria to access archived documents on the Markov case. Much of the evidence has been destroyed however, leading to accusations of a Bulgarian cover up – in 1992 General Vladimir Todorov, former Bulgarian intelligence chief, was sentenced to 16 months in jail for destroying 10 volumes of material relating to Markov’s death while two other individuals suspected of involvement in the assassination both died in mysterious circumstances in the 1990s – and Bulgarian prosecutors have now officially closed the investigation, under legislation which allows unsolved criminal cases to be dropped after 30 years.

Interestingly, ten days before Markov’s murder, a similar assassination attempt was made on another Bulgarian exile, Vladimir Kostov, while he was waiting at a Paris metro station. Like Markov, Kostov came down with a high fever and was hospitalized, where Doctors found the same kind of metal pellet embedded in his skin. On this occasion however, Kostov survived: possibly because he had not been shot at point blank range; possibly because the coating on the pellet had failed to fully dissolve, meaning that only a small quantity of Ricin was able to enter his blood or possibly because he was wearing a thick sweater on the day of the attack, which may have provided enough resistance to prevent the pellet completely penetrating his skin. However, Kostov’s case suggests that the attack on Markov may not have been an isolated case, but was perhaps intended as part of a wider strategy aimed at ‘silencing’ troublesome dissidents overseas. In the post-Cold War era, numerous cases including the dioxin poisoning of Ukrainian opposition leader (and later President) Viktor Yushchenko in the run-up to the 2004 elections; the still unsolved October 2006 murder of Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya and the November 2006 death of former KGB and FSB officer Alexander Litvinenko from radiation poisoning after exposure to polonium in London have drawn fresh comparisons with the Markov case, suggesting that when it comes to politically-motivated assassination, old communist-era habits may be hard to break.

(For a more detailed overview of recent cases suspected of involving politically motivated poisoning, see THIS Open Democracy article by Zygmunt Dzieciolowski).

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS