2011: A Quick Review

2011 is a year that has prompted numerous historical comparisons, even before it has ended. This has been a year marked by economic turmoil, widespread international protest and revolutionary activity, as evidenced by Time Magazine’s recent announcement that their coveted ‘person of the year’ was to be awarded to ‘The Protestor‘. Throughout 2011, global news coverage has frequently been dominated by the growing wave of protest and demonstrations that swept the Arab World; quickly dubbed the ‘Arab Spring’ by international media and drawing frequent comparisons with the East European revolutions of 1989. Some (including, recently, Eric Hobsbawm) have suggested that comparisan with the ‘Spring of Nations’ of 1848 is more fitting although many have questioned the value of either historical analogy. Similarly, almost twenty years to the day, in the last weeks of 2011, mounting protests against electoral fraud in Russia have evoked memories of the collapse of the communist monopoly of power and the break-up of the USSR in 1991, with the last Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev recently advising current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to ‘learn the lesson of 1991’ and resign from power, although Russia-watcher Mark Galeotti has suggested that 1905 may turn out to be a more fitting historical parallel.

The increasingly uncertain economic climate and global financial downturn also dominated news coverage throughout 2011, particularly of late due to the growing crisis in the Eurozone. Across central and eastern Europe, economic crisis and social insecurity has generated fresh concern about ‘ostalgie’ with the release of surveys suggesting high levels of nostalgia for the communist era. In recent polls conducted in Romania 63% of participants said that their life was better under communism, while 68% said they now believed that communism was ‘a good idea that had been poorly applied’. Similarly, a survey conducted in the Czech Republic last month revealed that 28% of participants believed they had been ‘better off’ under communism, leading to fears of a growth in ‘retroactive optimism‘.

Much of the subject matter presented here at The View East aims to combine historical analysis with more contemporary developments. During 2011 a range of blog posts have covered topics as diverse as the Cold War space race (with posts about Sputnik and the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin‘s first successful manned space flight); the role of popular culture (and specifically, popular music in the GDR) in undermining communism; the use and abuse of alcohol in communist Eastern Europe; espionage and coercion (with posts relating to the East German Stasi, Romanian Securitate and the notorious murder of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov) and in relation to continuing efforts to commemorate contested aspects of modern history including Katyn; the construction of the Berlin Wall, German reunification, Stalin’s legacy and the continuing controversy over Soviet-era war memorials. This summer also saw the first ‘student showcase’ here at The View East, which was a great success, with a series of excellent guest authored posts on a range of fascinating topics, researched and written by some of my students at Swansea University.

Something that I constantly stress to my students is the need to recognise how our knowledge and understanding of modern central and eastern Europe was, in many respects, transformed as new evidence and sources of information became accessible to historians of Eastern Europe after the collapse of communism 1989-1991; and the ways in which our understanding continues to evolve as new information and perspectives continue to emerge today. So, with that in mind, here is a quick review of some of my own personal favourite topics of interest, events and developments during 2011. This short summary is by no means exhaustive so please feel free to add suggestions of your own in the comments section below!

Anniversaries for Reagan and Gorbachev

February 2011 marked the centenary of Ronald Reagan’s birth. Today, former US President and ‘Cold Warrior’ Reagan remains highly regarded throughout the former communist block, where he is widely credited with helping to end the Cold War and open a pathway for freedom across Eastern Europe. A series of events were thus organised to mark the occasion across central and eastern Europe, where several streets, public squares and landmarks were renamed in Reagan’s honour and and the summer of 2011 saw statues of Reagan popping up in several former communist block countries, including Poland, Hungary and Georgia. To mark the centenary, the CIA also released a collection of previously classified documents, along with a report on ‘Ronald Reagan, Intelligence and the End of the Cold War’ and a series of short documentary style videos that were made to ‘educate’ Reagan about the USSR on a range of topics including the space programme, the Soviet war in Afghanistan and the Chernobyl disaster, which can be viewed here. An exhibition held at the US National Archives in Washington DC also displayed examples of Reagan’s personal correspondence including a series of letters exchanged with Mikhail Gorbachev and the handwritten edits made to Reagan’s famous ‘Evil Empire’ speech of 1983.

A statue of former US President Ronald Reagan, unveiled in the Georgian capital Tblisi in November 2011. The centenary of Reagan's birth was celebrated throughout the former communist block in 2011.

Today, citizens of the former East Block tend to view Reagan much more kindly than his Cold War counterpart, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev who celebrated his 80th birthday back in March. Still feted in the West, Gorbachev was the guest of honour at a celebratory birthday gala in London and and was also personally congratulated by current Russian President Medvedev, receiving a Russian medal of honour. In a series of interviews, Gorbachev claimed he remained proud of role in ending communism, although for many, his legacy remains muddied. April 2011 saw the 25th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, while August 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the failed military coup launched by communist hardliners hoping to depose Gorbachev from power and halt his reforms and finally, the 25 December 2011 was 20 years to the day since Gorbachev announced his resignation from power and the formal dissolution of the USSR. Recently released archival documents have also provided historians with more detailed information about the dying days of the Soviet Union as a desperate Gorbachev tried to hold the USSR together.

March 2011 - Russian President Dmitry Medvedev shakes hands with Mikhail Gorbachev during a meeting to celebrate his 80th birthday. Gorbachev was awarded the Order of St Andrew the Apostle, Russia's highest honour.

Half a Century Since the Construction of the Berlin Wall

August 2011 marked 50 years since the construction of the famous wall which divided Berlin 1961-1989 and became one of the most iconic symbols of Cold War Europe. The anniversary was commemorated in Germany as I discussed in my earlier blog post here and was also widely covered by international media including the Guardian and the BBC here in the UK. I particularly enjoyed these interactive photographs, published in Spiegel Online, depicting changes to the East-West German border. In October, the CIA and US National Archives also released a collection of recently declassified documents relating to the Berlin Crisis of August 1961, which have been published online here.

13 August 2011 - A display in Berlin commemorates the 50th anniversary of the construction of the Berlin Wall.

Thirty Years Since Martial Law Crushed Solidarity in Poland

13 December marked 30 years since General Jaruzelski’s declaration of Martial Law in Poland in 1981, as the emergent Solidarity trade union was declared illegal and forced underground. NATO have released a fascinating series of archived documents relating to events in Poland 1980-81 which have been published online here. Today Jaruzelski still argues that he ordered the domestic crackdown to avoid Soviet invasion, claiming in a recent book that his actions were a ‘necessary evil’ . but intelligence contained in the newly available NATO reports suggest that the Soviet leadership were actually ‘keen to avoid’ military intervention in Poland. Fresh attempts to prosecute 88 year old Jaruzelski for his repressive actions were halted due to ill health in 2011, as the former communist leader was diagnosed with lymphoma in March 2011 and has been undergoing regular chemotherapy this year.

13 December 2011 marked 30 years since General Wojciech Jaruzelski's declaration of Martial Law in Poland, designed to crush the growing Polish opposition movement, Solidarity.

The Communist-Era Secret Police

Stories about communist-era state security are always a crowd pleaser and 2011 saw a series of new revelations from the archives of the notorious East German Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or Stasi. I particularly liked the archived photos that were published in Spiegel Online, taken during a course to teach Stasi agents the art of disguise, as discussed in my previous blog post here and, in a similar vein, information from Polish files about espionage techniques used by Polish State Security which was published in October. In November, new research published in the German Press suggested that the Stasi had a much larger network of spies in West Germany than was previously thought, with over 3000 individuals employed as Inofizelle Mitarbeiter or ‘unofficial informers’, to spy on family, friends, neighbours and colleagues. The Stasi even compiled files on leading figures such as German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) and former East German leader Erich Honecker, gathering information that was later used as leverage to force his resignation in October 1989. A new book published in September also detailed the extent of Stasi infiltration in Sweden, with information published in the German media suggesting that Swedish furniture manufacturer IKEA used East German prisoners as a cheap source of labour in the 1970s and early 1980s.

‘Tourist with Camera’ – a favoured disguise used by Stasi surveillance agents, unearthed from the Stasi archives and part of a new exhibition that went on display in Germany earlier this year.

The Death of Vaclav Havel

2011 ended on something of a sombre note, as news broke of the death of communist-era dissident and former Czechoslovakian/Czech President Vaclav Havel on 18 December. An iconic figure, Havel’s death dominated the news in the lead up to Christmas, (only eclipsed by the subsequent breaking news about North Korean leader Kim Jong Il’s death on December 17!) with numerous obituaries and tributes to Havel and his legacy appearing in the media (such as this excellent tribute in The Economist, ‘Living in Truth‘), as discussed in more detail in my recent blog post here. Havel’s funeral on 23 December was attended by world leaders, past and present and received widespread media coverage. In recent interviews, such as this one, given shortly before his death, Havel commented on a range of contemporary issues including the Arab revolutions and the global economic crisis. RIP Vaclav – you will be missed.

December 2011 - News breaks of the death of playwright, communist-era dissident and former Czech President Vaclav Havel. Hundreds of candles were lit in Prague's Wenceslas Square in his memory, thousands of mourners gathered to pay their respects and tributes poured in from around the globe.

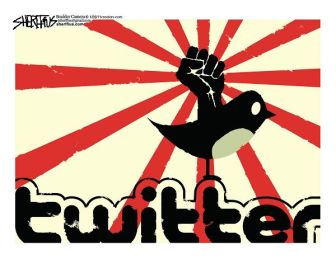

The Growth of Social Networking

The use of social networking as a tool for organising and fuelling protest and opposition movements has also been a regular feature in the news throughout 2011 with particular reference to the Arab Spring, the UK riots and the recent ‘Occupy’ movement. Many more universities and academics are also now realising the potential benefits of using social media sites to promote their interests, and achievements, disseminate their research to a wider audience and engage in intellectual debate with a wider circle of individuals working on similar areas of interest, both within and beyond academia. The potential benefits of Twitter and other social networking sites for academics has been promoted by the LSE and their Impact Blog during 2011, including this handy ‘Twitter guide for Academics‘. On a more personal note, promoting The View East via Twitter has also helped me develop a much stronger online profile and contributed to an increased readership in 2011, something I discussed further in a September blog post here.

As 2011 ends, our twitter feed @thevieweast is heading for 500 regular twitter followers; most days The View East receives well over 100 hits, the number of regular email subscribers has almost doubled and I’ve been able to reach a much wider audience – some older blog content I wrote relating to Solidarity was recently published in a Macmillan textbook History for Southern Africa and in the last twelve months I have given interviews to ABC Australia, Voice of America, and Radio 4, all in relation to subjects I’d written about here at The View East. So, as 2011 draws to a close, I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all of you who have read, commented, followed and re-tweeted from The View East in 2011 – A very Happy New Year to you all, and I’m looking forward to more of the same in 2012!

Inside Ceausescu’s Romania: An Unquestionably Efficient Police State

In 1989, when peaceful revolutions were sweeping across Eastern Europe, the fall of communism in Romania was marked by a higher level of violence and bloodshed than elsewhere in the region. This was due, at least in part, to the repressive nature of the regime established by Nicolae Ceausescu (1965-1989) and his loyal secret police, the Securitate. Estimates suggest that the Securitate had a higher proportion of representatives per population than anywhere else in the communist block and that by the 1980s as many as one person in thirty had been recruited as a Securitate informer. In this article, guest author Nelson Duque considers the deadly combination of Ceausescu’s distinctive style of dynastic socialism with the establishment of a brutally efficient police state, which enabled him to maintain an iron grip on power until the dying days of communist rule across Eastern Europe. Nelson briefly highlights the implications of some of the key policies enforced by Ceausescu and emphasises the key role of the Securitate in successfully ensuring the lack of any significant opposition, through the creation of a climate of fear and brutality.

Inside Ceausescu’s Romania: An Unquestionably Efficent Police State.

By Nelson Duque.

In post-war Romania the accession of the communists to power relied heavily on the use of coercion. Romania’s infamous secret police, the Department of State Security (DSS) or Securitate were established in August 1948, fashioned on the Stalinist-era NKVD, and trained by Soviet ‘technicians’. Throughout the communist era, the Securitate were used to maintain the Communist party’s hegemony in the face of any (real or imagined) opposition. The task assigned to the Securitate was to remove all enemies of the regime, by whatever means necessary. To this end, police oppression was widely employed, justified by those in power as a necessary means to weed out ‘class enemies’ or ‘counter-revolutionaries’ in the name of national security. Romania’s first Communist leader Gheorghiu-Dej (1945-1964) was the first to instigate a reign of terror; Dennis Deletant describes the Romanian people under Dej as having a ‘sense that they were being hunted’. However, Deletant goes on to describe Dej’s successor Nicolae Ceausescu’s rule (1965-1989) as an era marked by ‘fear rather than terror’, because Ceausescu did not copy Dej’s mass arrests and deportation policies on such an equal footing (Dennis Deletant, Ceausescu and the Securitate: Coercion and Dissent in Romania 1965-1989, Hurst: 1995). Surveillance, coercion and police terror not only remained hallmarks of Ceausescu’s Romania however, but many of these crimes were documented by the Securitate themselves. In the early 1990s, after the collapse of communism in Romania, extensive archived Securitate files totalled 35 kilometres of documents, 25 km of which comprised files containing information about victims of the Securitate, 4 km of files contained information about police informers, with 6km of other, various attached folders. Lavinia Stan has estimated that every metre of the archive contains 5000 documents and each individual file contained, on average, 200 pages in length.

The Securitate

It is still not known precisely how many Romanians were employed by the Securitate, partly as a consequence of the lack of material released since the collapse of Communism. Deletant estimates that from a population of 23 million people in 1989, available records indicate total DSS personnel of 38, 682.Virgil Magureanu, director of the SRI (Serviciul Roman de Informatii), which was formed on 26 March 1990 as the successor to the Securitate, estimates that in 1989 total Securitate personnel totalled only 14, 259, although this figure does not include those engaged in activities outside Romania, and Lavinia Stan suggests the continuity of influence between the Securitate and the SRI means that these figures cannot be trusted. The variance in figures between Magureanu and Deletant illustrates a long running debate over just how many individuals were employed by the Securitate. What is further unknown were how many people were hired to act as informers to the secret police, although this figure is considered to be extensive: Deletant simply categorises ‘tens of thousands of informers’ whom the Securitate, ‘by exploiting fear, was able to recruit’. It has been estimated that by the 1980s as many as one in every 30 Romanians was working as a Securitate informant.

The Securitate’s own records claimed that 97 percent of all informers were recruited voluntarily because of their ‘political and patriotic sentiment’, 1.5 percent were recruited through offers of financial compensation, and 1.5 percent through the use of blackmail with compromising evidence’.Frankly such statistics are farcical. Lavinia Stan estimates that between 400,000-700,000 part time informers were ‘employed’ by the Securitate and the chances of 97 percent of these being loyal to the regime is highly unlikely considering the low living standards and repressive policies in place under Ceausescu. Similar to the East German Stasi, fear was an essential method of recruitment employed by the Securitate, with threats and blackmail routinely used to coerce informants. It is likely that people dared not refuse the ‘offer’ of informing out of fear that they too would end up on the Securitate black list, marked as an ‘enemy’ or opponent of the state. The consequences could be serious; for example, World War Two veteran George Marzanca refused to collaborate with the Securitate and within a month he had been arrested and sentenced to four years imprisonment, on spurious grounds. In reality then there was often little real ‘choice’ in the matter; so perhaps it is little wonder that many people ‘willingly’ accepted informant status (Lavinia Stan, Inside the Securitate Archives).

Inside Ceausescu’s Police State

Ceausescu’s Romania was a unique case in Socialist Eastern Europe. From 1965, Ceausescu endeavoured to establish a dynastic form of Socialism; heavily reliant on his own ‘cult of personality’ with power concentrated in the hands of his close relatives including his wife Elena and their son Nicu. Ben Fowkes sees this relationship between family and state as detrimental to society, describing Ceausescu as ‘both incurably Stalinist and fiercely repressive’ (Ben Fowkes, The rise and fall of Communism in Eastern Europe, Macmillan: 1995). Unsurprisingly, the secret police were some of Ceausescu’s most loyal agents, carrying out his will during the 23 years of his rule. During this time far reaching policies such as widespread austerity measures, ‘systematisation’ and pro-natalism were all enforced by the Securitate. These policies illustrate prime examples of how the Ceausescus’ directly interfered in and influenced the lives of ordinary Romanians and of how the Stasi employed insidious and brutal tactics to ensure a lack of opposition.

Ceausescu’s policy of ‘Systematisation’ (rural relocation linked to urban planning) destroyed at least half of Romania’s 13,000 villages, allocating the rural population to new fangled ‘agro-towns’ (Tony Judt, Post war A History of Europe since 1945, Pimlico: 2007) The majority of the villages destined to be destroyed were predominantly inhabited by ethnic minorities (Hungarians, Germans and Roma). The targeting of ethnic Hungarians in a town called Dej met with initial opposition from Laszlo Tokes, who was a pastor with the Hungarian Reformed Church. Tokes gained widespread support within his parish and as a result he was soon targeted by the Securitate. Tokes and his friends were placed under constant surveillance and subject to daily harassment until pressure on the clergy eventually led to Tokes removal and enforced ‘deportation’ to a village 40 kilometers from Dej, in 1982 . The example of Tokes is telling in a number of respects: demonstrating the use of extensive coercion by Securitate agents; illustrating the lengths to which the regime would go to get rid of an opponent and exemplifying the power of the state over the Reformed Church; as members of the clergy could be forced to denounce their staff at the will of the party.

The case of Tokes further highlights the use of intimidation, brutality and terror tactics by the Securitate. A second attempt to deport Tokes was issued on 20 October 1989; this time he was ordered to leave the town of Timisoara, where he had been reluctantly appointed after the involvement of the US senate. After his refusal, on 2 November, four attackers armed with knives broke into the flat, ‘while Securitate agents looked on’. Fortunately Tokes survived thanks to his friends fighting the attackers off, but this instance indicates the willingness of the Securitate to tolerate state sanctioned murder. The second attempt to deport Tokes was met by a united public outcry from both Romanians and Hungarians. Demonstrations in Timisoara on the 16 and 17 December 1989 were combated with heavy-handed brutality from the Army and the Securitate. The number of casualties was initially estimated at several thousand, but subsequent investigations put the figure at 122. The brutal repression in Timisoara was directly ordered by Elena Ceausescu while Nicolae was on state business abroad, and she subsequently also ordered the cremation of 40 bodies to avoid their identification. This event was to play a clinical role in triggering the revolution of 22 December 1989, which would overthrow the Ceausescus’ from power and lead to the collapse of Communism in Romania (K. McDermott and M. Stibbe (Eds), Revolution and Resistance in Eastern Europe, Berg: 20o6).

Elena Ceausescu was also responsible for the serious death rate amongst women through her influential pro-natal policies. As chairperson of the National Women’s Council she nationalised what should have been a private affair, supported by her husband’s rhetoric that a pregnant woman was ‘everybody’s concern’ because family life was a ‘socialised private problem’ (Mark Almond, The rise and fall of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, Chapmans: 1992) . Concern over falling birth rates meant that the megalomania of the Ceausescus’ thus even extended into the bedroom, with propaganda claiming that it was a woman’s duty to rear children for her country. Methods of birth control, including condoms and the contraceptive pill, were either not available or routinely failed quality control. Disturbingly, this resulted in abortion being the only means of contraception for many women, and even this was criminalised in 1966, forcing many women to risk illegal abortions. Securitate agents were stationed at gynaecological wards and were supposed to report on any women who requested an abortion, although they could often be bribed to ‘turn a blind eye’. However, it has been estimated that between 1966 – 1989 this policy resulted in the death of at least ten thousand women and over 100,000 institutionalised children kept in appalling orphanages (Tony Judt, Post war A History of Europe since 1945, Pimlico: 2007).

Maintaining Control, Ensuring Conformity

Due to the effectivness of their repression and brutality, Ceausescu’s Securitate were described as ‘the envy of other dictators’ (Walter Laqueur, Europe in our Time: A History 1945-1992, Penguin: 1992). As a result of their influence, there was little dissidence and virtually no organised opposition to Ceausescu’s regime. The example of Paul Goma, a dissident writer, illustrates the serious consequences that could result from individuals who were brave enough to take a public stand against the injustices of the regime. From the mid 1970’s Goma began to highlight the human rights abuses taking place under the Ceausescu regime, and even sent a letter to Ceausescu in early 1977 asking for his signature to express solidarity with ‘Charter 77’, the human rights movement in Czechoslovakia. Unsurprisingly, Goma became a target for the Securitate shortly afterwards: he was harassed by threatening phone calls; his street was cordoned off by the police and most notoriously Horst Stumpf, a former professional boxer, broke into his flat three times within a matter of days, assaulting Goma on each occasion whilst the police did not intervene despite being called. In November 1977, Goma was forced into exile in France.

Writer Paul Goma's public criticism of Ceausescu's regime led to his becoming a target for the Securitate. After being subjected to harrassment and physical attacks, Goma left Romania for France in 1977.

This lack of opposition in either the political or the public sphere also explains how Ceausescu managed to put forward such highly ambitious, yet absurd, economic policies. Official statistics claimed that throughout the 1970’s there was an economic growth rate of between 6-9 percent annually in Romania, with an investment rate of up to 30 percent.Yet the regime was outwardly lying about its economic development. In reality, Romania was impoverished and starving, with Ceausescu’s austerity measures involvi ng the exportation of almost all agricultural surplus; frequent power cuts and shortages of basic goods, foodstuffs and medical supplies with the population dependent on ration cards. Ceausescu may have succeeded in paying off Romania’s $13 million foreign debt by the end of the 1980s, but his oppressive policies forced many of his own people to near-starvation.

When communism in Romania finally collapsed in December 1989, the Ceausescus’ were the only East European leaders to face immediate trial. A summary of the Ceausescus’ crimes (and those of the Securitate) are documented in their trial transcript, from 25 December 1989. Here the prosecutor accuses Nicolae Ceausescu of ‘Crimes against the people … Genocide … armed attack on the people … destruction of buildings and state institutions, undermining of the national economy’. The prosecution makes disturbing reading, Nicolae and Elena do not acknowledge their crimes and the reality of their circumstances, despite being accused of killing children and leaving people with ‘nothing to eat, no heating, no electricity’. The prosecutor Gica Popo also demanded to know who gave the order to shoot in the Timisoara uprising, and surprisingly Elena and Nicolae blame the Securitate, accusing them of being ‘terrorists’ who killed indiscriminately; they also deny being in charge of the Securitate, although it was common knowledge that the Ceausescus’ had authorised their acts of terror. Following a hurried trial by military tribunal, both Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were sentenced to immediate execution via firing squad.

Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were tried by a Military Council and sentenced to execution via firing squad for crimes against the Romanian people on 25 December 1989.

It is clear that Ceausescu’s Romania was an unquestionably efficient police state. The lives of many Romanians were dominated by fear. The crimes of murder, brutality, coercion, deportation and genocide were all associated with the leadership and with the notorious Securitate, right up until the dying days of communism in 1989. The legacy of Ceausescu’s reign still haunts Romania today, as they continue to try to break from their repressive past.

About the Author:

Nelson Duque has just completed his BA (Hons) in History at Swansea University, graduating in July 2011. During the final year of his degree, Nelson specialised in the study of Communist Eastern Europe. Nelson will begin a PGCE at the University of Warwick in September 2011.

Student Showcase: Forthcoming Guest Authored Blog Posts by Swansea University Students.

During July, The View East is very pleased to be hosting a ‘student showcase’, featuring a number of short articles written by history students from Swansea University.

During the final year of undergraduate study, many students invest a lot of time and energy into their studies and produce some really excellent work as a result. However, the vast majority of work produced by undergraduate students is generally not accessible to a wider audience. Most dissertations, essays and research projects are read only by the student themselves, their supervisor, one or two other examiners and perhaps a couple of family members or close friends who may be drafted in to proofread the finished article. Reading through some of the excellent work submitted by students I’ve worked with at Swansea University over the course of the last year led me to reflect that this was rather a shame. Hence my idea to host a ‘student showcase’ here on The View East was born, by asking some of my students to write short articles related to some of the research they had conducted over the past year.

The students I approached have risen admirably to the challenge! Over the next three weeks The View East will feature seven short guest authored articles. All articles have been written by students from the Department of History and Classics at Swansea University. All of the authors have recently completed the final year of their undergraduate degrees and will be graduating this month. All of the students featured here either took my ‘special subject’, specialising in the study of Eastern Europe 1945-1989 during the final year of their degree, or chose to research and write their dissertation on some aspect of modern East European history, under my supervision. All of the students featured as guest authors consistently produced excellent work over the course of the year, just a small sample of which is included here. Sadly, it was not possible to feature the great work done by all of the students I have had the pleasure of working with this year, as many (particularly in the case of my dissertation group) produced excellent research, but on topics that lie outside of the scope of this blog’s focus.

By way of a brief introduction, our guest authors during the next three weeks are writing on the following topics:

Week 1:

On Monday 11 July we begin with Harry Hopkinson’s fascinating article Sputnik: Bluff of the Century. Here Harry explores the implications of the successful launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union in 1957, not only in terms of technological and military developments but also in terms of its wider impact on the development of the Cold War.

On Wednesday 13 July we have the first of a trio of articles focusing on various aspects of the history of the GDR. In this article Rosie Shelmerdine provides a fresh and timely analysis of the 1953 East German Uprising, exploring the true nature of the rebellion by asking whether the events of June 1953 are best considered as ‘Western Provocation, Workers Protest or Attempted Revolution?’.

Our first week concludes on Friday 15 July, with James Shingler’s intriguing article ‘Rocking the Wall’, which follows on nicely from Rosie’s study of a popular uprising by exploring a rather different aspect of protest and resistance in the GDR, focusing on the impact of popular music in 1970s and 1980s East Germany.

Week 2:

The second week of the student showcase opens by concluding our focus on the GDR. On Monday 18 July David Cook’s article ‘Living with the Enemy’ provides an insightful and intelligent analysis of the infamous East German secret police – the Stasi.

On Thursday 21 July Nelson Duque’s article ‘Inside Ceausescu’s Romania: An Unquestionably Efficient Police State’ follows nicely on from David’s study of the Stasi by considering the repressive nature of another East European regime: that of Ceausescu’s Romania and his much feared secret police, the Securitate.

Week 3:

On Monday 25th July our penultimate article, written by Carla Giudice, takes us back to the immediate aftermath of World War Two by considering some of the factors that influenced the contrasting fates of three leading individuals who featured in the 1945 Nuremberg War Crimes Trials: the ‘Good Nazi’ Albert Speer, the ‘Bad Nazi’ Herman Goering and the ‘Mad Nazi’ Rudolf Hess.

In recent months there has been a renewed focus on war crimes in relation to the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, due to the recent arrest and indictment of former Bosnian Serb Army chief Ratko Mladic on charges of genocide and other crimes against humanity. On Wednesday 27th July, our final guest authored article by Simon Andrew thus provides a fitting conclusion to the student showcase, by considering some of the circumstances surrounding the bloody break up of Yugoslavia.

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS