Living with the Enemy: Informing the Stasi

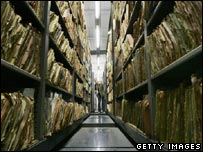

The East German State Security Service, commonly known as the Stasi, was founded in February 1950. For forty years, the Stasi maintained a frightening reputation for surveillance, infiltration and terror, leading Historian Timothy Garton Ash to comment that the word ‘Stasi’ has become ‘a global synonym for the secret police terrors of communism’. The tentacles of Stasi power and influence were so far reaching that it was recently revealed that the Stasi had even compiled a secret dossier on Erich Honecker, leader of the GDR 1971 – 1989; using information obtained about Honecker’s attempts to collaborate with the Nazis during the Second World War to force him to resign in October 1989. In January 1990, shortly after the collapse of communism in the GDR, crowds of protestors stormed and occupied the Stasi headquarters in Berlin; an act symbolising the people’s victory over one of the greatest evils of state socialism in the GDR. The Stasi kept meticulous records about those placed under surveillance, with over 180km of shelved Stasi files surviving the collapse of the GDR. In the post-communist years this information was declassified and between 1992 and 2011 an estimated 2.75 individuals have requested access to their files. In many instances people discovered that people they had trusted – family members, close friends, neighbours and work colleagues – had worked as informants for the Stasi. In this article, guest author David Cook explores the key role played by Stasi informers in the GDR, considering the motivations of those who agreed to work with the Stasi and the impact of popular participation on wider society.

Living with the Enemy: Informing the Stasi in the GDR.

By David Cook.

The German Democratic Republic (GDR) was the golden child of the Soviet Union, often portrayed as the torch bearer for the communist system around the world. Yet its people still could not be allowed the freedom to air their individual opinions, the views of the state were final and absolute, and to contradict the party was considered no less serious a crime than treason itself. A powerful police organ was needed to keep the people in check, a progenitor of fear that would bend the populace to the will of the state. In the GDR the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi, was the tool used to attempt to mould the East German people to the Communist Party’s (SED) requirements. However, police and party pressure alone is not enough to oppress an entire country; popular participation is ultimately key to any regime’s survival. In the case of the GDR, its own people helped to maintain the party’s power through their role as police informers. Informers played a crucial role, acting as a vital cog in the vast machinery of the East German police state; both responding to and perpetuating the climate of fear that permeated throughout East German society.

By 1989, when the Berlin Wall collapsed and communism in East Germany came to an end, it is estimated that the MfS had 97,000 official employees as well as approximately 173,000 unofficial informers. Roughly this translated as a ratio of one agent per 63 of the population, a position far in advance of the Soviet Union’s KGB, that even at its height could only manage one per 5830 people (Figures taken from Anna Funder, Stasiland, Granta: 2004). The Stasi amounted to a small army infiltrating the very fabric of the communist regime, whose sole purpose was the surveillance and repression of the East German people. Fear of the state – and of the Stasi as a tool of state control – was widespread, and this terror was used as a vital tool in the creation of a malleable citizenry.

The Stasi motto 'Schild und Schwert der Partei' declared its intention to act as the 'Shield and Sword' of the Communist Party in East Germany.

There were a variety of things that could bring a person to the attention of the Stasi. Once the MfS had targeted a suspect the goal was often to engender self-doubt in that person, to prevent them from living any semblance of a normal life, and if indeed they were guilty of some form of ‘subversion’, to encourage them to further implicate and discredit themselves. Ulrike Poppe was one such individual whose work in dissident peace and feminist movements were deemed to be a threat to the stability of communist East Germany by the Stasi. Between 1973 – 1989, Poppe was arrested a total of 14 times. For 15 years she was placed under surveillance, followed by her own personal MfS agent and subjected to daily harassment. In this way the Stasi undermined their targets’ self-confidence and peace of mind, rather than physically beating them. Although physical coercion was employed by the Stasi, the evidence indicates that they often preferred to utilise more ‘subtle’ (but equally effective) means of psychological torture. Isolation, sleep deprivation, disorientation, humiliation, restriction of food and water and ominous threats against the subject and their families combined with promises of leniency if they ‘confessed’ were all commonly cited interrogation tactics. The MfS was not concerned with human rights and paid no more than lip service to the notion of a democratic legal process and legitimate trials, as illustrated by the head of the Stasi, Erich Mielke, who maintained a policy of: ‘Execution, if necessary without a court verdict.’

One victim’s memories of Hohenschönhausen, the feared Stasi prison in East Berlin:

For the police state to function fully however, participation from amongst the populace was key. Their vital tool here was to be the Inofizelle Mitarbeiter (I.M). IMs were unofficial collaborators who informed on work colleagues, friends, and even their own spouses. Informers were a part of everyday life, supplying the Stasi with the banal trivialities that they deemed necessary to neutralise their targets. During the lifespan of the communist regime in East Germany it is estimated from existing archival material that there were up to 500,000 informers active at various times. Or more starkly one in 30 of the population had worked for the Stasi by the fall of the GDR. Informers were controlled by their own special department, HA IX (Main Department 9), often referred to as ‘the centre of the inquisition.’

People were not often willing informers however, and it would be wrong to accuse the majority of East Germans of freely consenting to work with the Stasi. Motives for becoming an informer appear to be numerous, and this topic has provided the basis for many historical works. Yet as crucial as they were to the oppression of the population, what drove so many East Germans to inform on their own people? Robert Gellately in his article, Denunciation in 20th Century Germany, posits a view of a ‘culture of denunciation’ that was a hangover from the Nazi period. People became I.Ms for a number of reasons in his view: for personal gain; so visits to the West would be granted; from a desire to change the system from within; or in the majority of cases through blackmail and coercion by the Stasi. Fear then, was also used as a tool to recruit informers from the general populace.

Timothy Garton Ash’s book, The File, is based on his own personal Stasi file as he tracks down and talks to many of those that informed on him, noting the motivations behind their actions. Each of the informers exhibits differing reasons for their collaboration, all of which are covered by Gellately’s theory. ‘Michaela’ was an art director and as such was encouraged to inform on those the Stasi deemed interesting in order to make her job easier. Visas enabling visits to art exhibits in the West or much needed budget increases could be obtained in exchange for information. Whilst ‘Michalea’ was an example of someone working for the police state for personal gain, two other examples in Garton Ash’s book were recruited through blackmail. ‘Schuldt’ was persuaded to become an informer due to fear of his homosexuality being made public and his life ruined; ‘Smith’ on the other hand collaborated to prove his innocence in the face of accusations of being a Western spy. In this way the Stasi was able to build up a frighteningly vast network of informers utilised to collate data on anyone deemed of interest to the state.

Stasi Files Department, Berlin. The Stasi kept meticulous files on all individuals under surveillance, the majority of which survived the collapse of communism and are now accesible to the public.

Fear, as illustrated in the cases of ‘Smith’ and ‘Schuldt’, was the most powerful weapon possessed by the Stasi. It was a weapon they utilised freely, creating large networks of informers and ensuring the system survived. The MfS were the source of this fear in society at large, creating a resigned conformity amongst the masses that kept them subordinate to the whims of the SED. This is the crucial role played by the security apparatus in a truly repressive police state. Without the conformity of the lower levels of society the system would have collapsed. The majority of the population learned, from a dread of the consequences, to live with this authority in return for living a semblance of a peaceful life. Reicker, Schwarz and Schneider describe the day to day life of a GDR citizen as such: ‘The daily lie, which everyone participated in to some extent … Once you learn to accept the big political lie you allow yourself little lies in other places. Unconsciously.’ It was this willingness by the German population to be subjected to authority, and the all powerful nature of the MfS, that Funder argues led to the relatively low level dissident movement within the GDR.

Everyday life was pervaded by the party ideology, the individual was disregarded and the regime elevated above it. Virtually no corner of life was left untouched by the influence of the party and its ‘guard dog’, the Stasi. The security apparatus infiltrated and manipulated the educational sector; determining who could study at university and which subjects were ‘suitable’ for academic research and teaching, with almost a quarter of staff at the East German Humboldt university in the Stasi’s employ. All communication in and out of the communist state was monitored and intercepted by the MfS. In East Berlin, 25 phone stations enabled the tapping of up to 20,000 calls simultaneously. Figures show that 2,300 telegrams a day were read by the Stasi in 1983 alone. Interception of packages also proved to be a favoured method of state security, and one that provided rich dividends. Estimates taken from surviving archival material put the figure of currency seized by the MfS as equalling 32.8 million DM. (Figures taken from Mike Dennis, The Stasi: Myth and Reality, Longman: 2003)

Life was controlled by the MfS and the SED, with all methods utilised to prevent contact with the western world. People adapt however, and East Germans developed ‘coping mechanisms’. Secret codes and gestures were developed to indicate when known Stasi informers or operatives were nearby. Even today the terror of the MfS remains a powerful force in the everyday life of former GDR citizens, acting as a kind of ‘wall in the mind’. Claudia Rusch, the daughter of an East German dissident, leaves no doubt as to the GDR’s status as a police state in her description of life under the former regime:

“That was the real strength of the state security; to produce the effect that millions of people behaved towards one another with anxiety, self-control and suspicion. They ensured that if you told a political joke you automatically lowered your voice. Anticipatory obedience spread through every sinew of society and intimidated a whole nation”.

(Claudia Rusch, quoted in Mary Fulbrook, The People’s State, Yale University Press: 2005)

The people of East Germany were browbeaten by the Stasi’s propagation of fear, its far reaching tentacles spread through society in the form of informers hidden in plain sight. Any person deemed of particular interest had an MfS file which would contain an almost minute-by-minute account of the suspect’s life, from which the MfS could create any motive for action they deemed necessary. Fear pervaded all aspects of life in the GDR, the population cowed by the threat of MfS reprisal, unable to build the foundations for an opposition movement. In the pursuit of blanket surveillance of the population, the Stasi gained a terrifying level of power over the East German people and could manipulate them at their whim. Agents of the state were everywhere, in the workplace, the classroom and even sleeping in the same bed. In this way conformity was enforced through implicit, rather than explicit terror.

About the Author:

David Cook has just completed his BA (Hons) in History at Swansea University, graduating with first-class honours in July 2011. During the final year of his study he specialised in the study of Cold War Eastern Europe. Following university David plans to travel, before eventually undertaking a Masters degree in History.

For more information on this topic see:

Timothy Garton Ash, The File: A Personal History, (London: Atlantic Books, 2009)

Mary Fulbrook, Anatomy of a Dictatorship: Inside the GDR 1949-1989, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995)

Mary Fulbrook, The People’s State: East German Society from Hitler to Hoenecker, (London:YaleUniversity Press, 2005)

Anna Funder, Stasiland: Stories From Behind the Berlin Wall, (London: Granta Books, 2004)

Robert Gellately, Denunciations in 20th Century Germany: Aspects of Self-Policing in the Third Reich and the German Democratic Republic

15 Comments »

Leave a reply to rossozarka Cancel reply

-

Archives

- November 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (4)

- November 2014 (2)

- October 2014 (1)

- September 2014 (1)

- June 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (2)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

[…] Cook at The View East writes about the East German security police, Stasi, during the Cold War, and its system of informers. […]

Pingback by Germany: Stasi and its Informers · Global Voices | July 18, 2011 |

[…] Cook van The View East schrijft over [en] de Oost-Duitse geheime dienst, de Stasi, tijdens de Koude Oorlog, en over het systeem van […]

Pingback by Duitsland: De Stasi en hun informanten · Global Voices in het Nederlands | July 18, 2011 |

[…] The Stasi. […]

Pingback by Stones Cry Out - If they keep silent… » Things Heard: e182v2 | July 19, 2011 |

I am writing a blog about my time in Prague 1970, based oin the letters I wrote home at the time and our memories of living in eastern Europe. http://ironcurtainletters.blogspot.com/

You might find it interesting.

Another great piece of work Kelly, as always substantial reading and educational. Missed reading your blogs last couple of weeks, making up for it today. Thank you 🙂

Kate

[…] For more on the Stasi, see the previous post by guest author David Cook ‘Living with the Enemy: Informing the Stasi’. […]

Pingback by Recent Revelations from the Stasi Archives. « The View East | August 3, 2011 |

Informative article, thanks for taking the time to post this in your blog.

[…] alcohol in communist Eastern Europe; espionage and coercion (with posts relating to the East German Stasi, Romanian Securitate and the notorious murder of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov) and in relation […]

Pingback by 2011: A Quick Review « The View East | December 31, 2011 |

Reblogged this on USA COINTELPRO VICTIM OF POGs PATRIOT & SPACE PRESERVATION ACTS.

[…] to lamp posts in downtown Colorado Springs? It turns out that the City of Colorado Springs has stolen a page from the East German communist playbook, using citizen “police volunteers” to monitor these cameras and call in crimes that […]

Pingback by Colorado Peak Politics - POLICE STATE: Colorado Springs Police Collaborating with “Police Volunteers” to Make Arrests | June 3, 2013 |

[…] have been the modus operandi of the state, perhaps no better than in Stasi-era East Germany, where neighbor turned upon neighbor, as was witnessed following the Boston marathon bombing. My concerns are not intended to perpetuate […]

Pingback by A real horror show | Deconstructing Myths | July 3, 2013 |

[…] pranešimus interneto skelbimų portaluose. O Rytų Vokietijoje, Šaltojo karo įkarštyje, 1 iš 63 žmonių buvo informatorius. Pasauliniame kaime sklandys gandai. (Simon Ings […]

Pingback by Būsimi žmonijos 1000 metų - Robotika.lt | November 18, 2014 |

I have a question. What did the communist party stand to gain from maintaining an anxious citizenry under constant surveillance?

[…] (2010) The Firm: The Inside Story of the Stasi. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cook, D. (2011) ‘Living with the Enemy: Informing the Stasi in the GDR,’ The View East. Curry, C. (2008) ‘Piecing Together the Dark Legacy of East Germany’s Secret […]

Pingback by Fearsome or Futile? The Limitations of Stasi Surveillance in East Germany. « The View East | July 23, 2015 |

This is very interesting and has been very helpful for my dissertation. However, I was wondering if you knew where I could find information on people that have viewed their Stasi file after 1992 and how they felt it had effected them? Thank you.